Task Sharing in Family Planning: Increasing Health Workforce Efficiency to Expand Access to and Use of Quality Family Planning Services

What is the program enhancement that can intensify the impact of High Impact Practices in Family Planning?

The systematic and planned expansion of the range and level of trained, supervised, and skilled healthcare professionals who can safely deliver quality contraceptive and family planning services, resulting in essential and equitable redistribution of services.

Midwives after attending a successful birth in Nhamatanda Hospital, Mozambique. © 2012 Arturo Sanabria, Courtesy of Photoshare

Download Brief

Background

High-profile global partnerships and initiatives such as FP2030, the International Conference on Population and Development 30 (ICPD30), and the Ouagadougou Partnership highlight the importance of family planning as a global, national, and subnational imperative. Family planning contributes directly to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals 3 and 5 and indirectly to the other 15 SDGs.*

Family planning is a proven cost-effective, efficient, and sustainable key intervention that can help reach global and country goals in saving the lives of women and children.1

A major obstacle to accessing quality contraceptive services in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is the limited number of trained healthcare providers. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports a global shortfall of more than 17 million healthcare workers, with the most severe gaps in rural areas, often the same communities with high unmet need for contraception.2

Task sharing—an existing safe, effective, and efficient strategy—can help alleviate that shortfall, as well as improve access to care, equity, and cost-effectiveness.1

“Task sharing” refers to the strategic redistribution of tasks within healthcare workforce teams, or cadres, and personnel.† Specific tasks, where appropriate, are moved, shared, or delegated, usually from highly trained healthcare workers to those with less training or fewer qualifications, to make more efficient use of the available personnel.1,3

By strategically reallocating responsibilities, task sharing improves overall workforce efficiency. It has the potential to mitigate critical systemic challenges, including worker shortages and uneven distribution of qualified and trained healthcare providers. Importantly, task sharing should go hand in hand with proper actions in education, supervision, management support, licensing, regulation, and pay.‡

Task sharing operates across policy, health systems, and community levels, engaging multiple stakeholders throughout implementation. For family planning and other voluntary sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, task sharing fosters universal health coverage by expanding coverage to underserved populations. By deploying a wide range of healthcare providers, such as community health workers (CHW), midwives, and other nonspecialists, rather than doctors and nurses for specific responsibilities, task sharing enhances the reach, affordability, availability, and cost-effectiveness of family planning services, particularly in rural regions, humanitarian settings, and areas affected by crisis.3,4 The Guttmacher Institute’s most recent Adding It Up model finds that adopting WHO task sharing guidance for contraceptive services could reduce delivery costs by 28%, or about $1.6 billion, in 128 LMICs.3

By expanding the spectrum of healthcare workers delivering family planning services, task sharing helps bridge gaps in access to high-quality voluntary family planning and other SRH services and increases healthcare workforce efficiencies by equipping a wider range of providers to deliver key elements of these services. For healthcare providers, task sharing offers opportunities for professional skills and development, career progression, and personal growth by acquiring new knowledge and skills, and by mentoring and receiving positive feedback from colleagues, managers, patients, and the wider community.5,6

The impact of evidence-based family planning interventions and High Impact Practices (HIPs) is bolstered when responsibilities for delivering high-quality contraceptive services are optimally shared and distributed across different types of service providers within the healthcare system. To support task sharing and an extension of the healthcare services team, cadres may cover for each other, and providers share tasks across cadres. The focus is on improving collaboration and thus effectiveness among clinical teams, and on providing quality services.

Task sharing implementation in countries from Burkina Faso and Kenya to Pakistan and Bangladesh shows the value of extending the scope and reach of the healthcare workforce in quality of care improvements as well as increased service coverage, method uptake, and demand creation.7–13

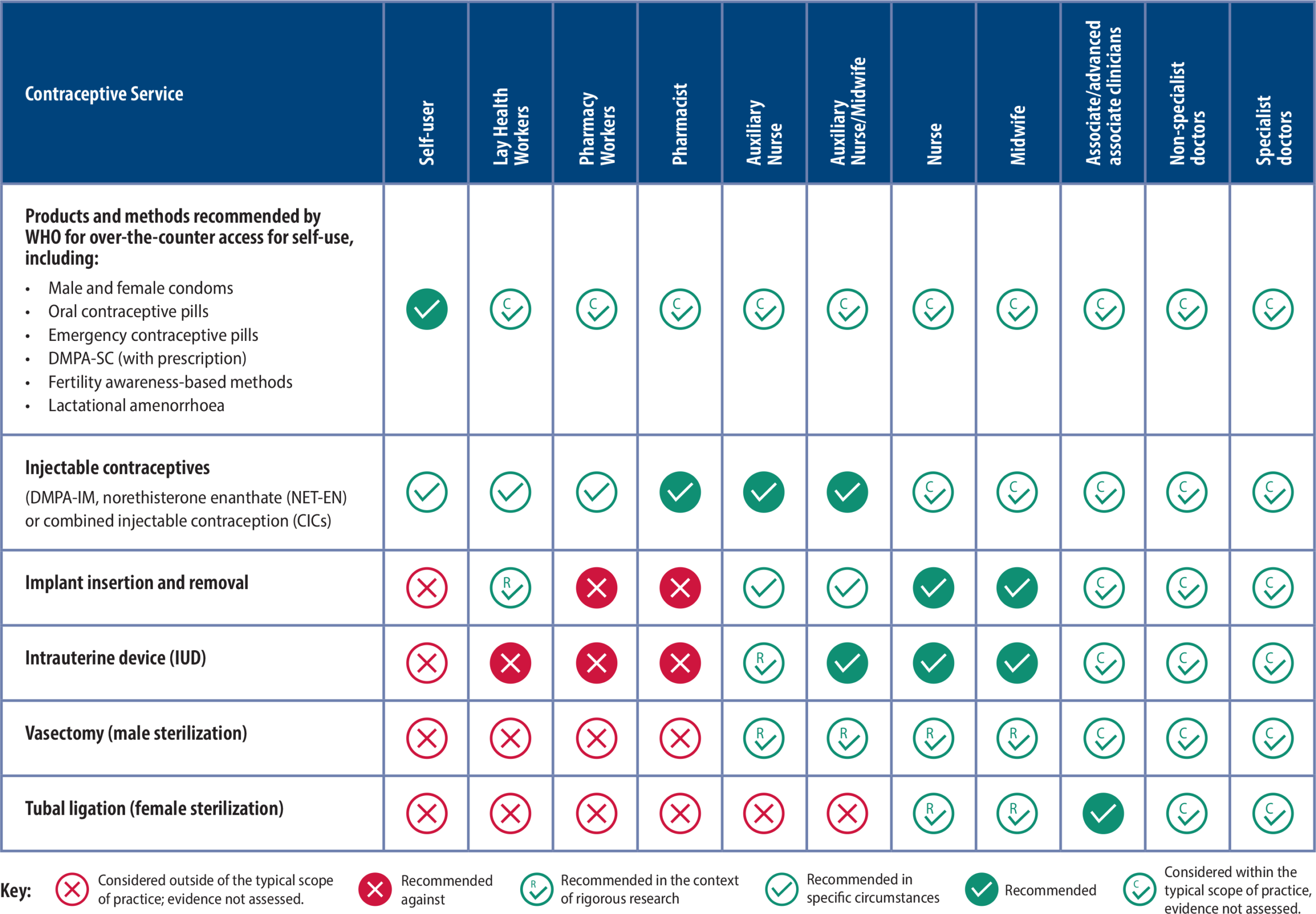

Healthcare provider cadres identified within WHO recommendations for participation in task sharing for family planning are noted in Table 1.

* SDG 3, “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages,” and SDG 5, “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.” See SDGs here.

† A cadre is a group of people specially trained for a particular purpose or profession. Health profession cadres may include nurses, community health workers, pharmacists or pharmacy assistants, or other trained lay health workers.

‡ “Task shifting” is commonly used to refer to transferring responsibilities from highly specialized health workers to those with less specialized training, but the term is discouraged, as it often suggests merely offloading tasks without the supportive measures that are essential in task sharing. Guidance on Planning, Implementing and Scaling Up Task Sharing for Contraceptive Services, World Health Organization, 2025; https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240111486.

Recommendations for Task Sharing in Contraceptive Services

How can this practice enhance HIPs?

Task sharing is an enhancement to the High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs) identified by the HIPs Technical Advisory Group. An enhancement is a practice that can be implemented in conjunction with HIPs to intensify their impact. HIPs fall into three categories—enabling environment, service delivery, and social and behavior change—and task sharing enhances HIPs within each of those categories.

The impact of evidence-based HIPs is boosted through task sharing (Table 2). Task sharing approaches affect every HIPs category, strengthening the implementation impact across the HIPs categories. For more information on HIPs, see https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org.

How Task Sharing Enhances HIPs Implementation

HIPs Category and Practice Examples | Task Sharing Enhances the Practice by … | Illustration |

Enabling Environment Comprehensive Policy Processes: The agreements that outline health goals and the actions to realize them Domestic Public Financing: Building a sustainable future for family planning programs Galvanizing Commitment: Creating a supportive environment for family planning programs | Building private sector capacity to provide a broader range of family planning methods through training and expanded cadres in service provision. Strengthens linkages between public and private sector systems. How: Boosts cost savings and cost-effectiveness; reduces out-of-pocket expense; expands cadre-inclusive policy and regulation | Organizing service delivery to optimize the healthcare workforce, such as through task sharing, may lower the cost of family planning services by reducing healthcare worker time required and achieving economies of scale in training and supervision.1,15,16 |

Service Delivery Immediate Postpartum Family Planning: A key component of childbirth care Postabortion Family Planning: A critical component of postabortion care Family Planning and Immunization Integration: Reaching postpartum women with family planning services Community Health Workers: Bringing contraceptive information and services to people where they live and work Pharmacies and Drug Shops: Expanding contraceptive choice and access in the private sector | Allowing a broad range of healthcare providers to meet client needs through integrated service delivery to achieve healthcare system efficiencies, provide comprehensive client-centered care, and reach communities that may be less likely to seek stand-alone family planning services. How: Increases access to family planning care performed by nurses and midwives; improves efficiency; provides access to counseling | In India until 2009, only doctors were authorized to provide intrauterine devices postpartum, yet most deliveries were attended by nurses and midwives. Development partners worked with the government to demonstrate that nurses and midwives could safely and effectively provide IUDs during the immediate postpartum period.15 |

Social and Behavior Change Knowledge, Beliefs, Attitudes, and Self-efficacy: Strengthening an individual’s ability to achieve their reproductive intentions Community Health Workers: Bringing contraceptive information and services to people where they live and work Digital Health for Social and Behavior Change: New technologies, new ways to reach people | Supporting client-centered access to products and services through preferred and convenient service delivery points. Educates communities about SRH services and family planning methods, access points. How: Increases community engagement; improves scaling up of services; increases access to their preferred method of contraception via their preferred providers | Community-level provision of implants in Ethiopia through healthcare extension workers has expanded access to long-acting family planning methods.16 Improved education breaks down barriers, fosters trust, and dismantles stigma and family planning myths and misconceptions.4 |

Enhancement Adolescent-Responsive Contraceptive Services: Institutionalizing adolescent-responsive elements to expand access and choice Digital Health to Support Family Planning Providers: Improving knowledge, capacity, and service quality Digital Health for Systems: Strengthening family planning systems through time and resource efficiencies | Developing policies that support access to contraceptive information and services for adolescents, regardless of age, parity, or marital status; training and supervising healthcare service providers; using a variety of service delivery models and providers.14 Digital healthcare and telehealth expansions have included expanded cadres. How: Increases adolescents’ access to family planning; improves satisfaction of clients and providers; friendly to rural and key populations | Telehealth, which entails providing healthcare remotely through various communication tools, is a digital approach emerging within family planning programs, particularly in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.17 Provider-to-provider telehealth can facilitate communication for consultations on case management, requesting second opinions, peer-to-peer mentoring, or coordinating care. When varied cadres across the healthcare team participate and collaborate within telehealth programming, digital approaches are improved.18 |

What is the influence of task sharing on family planning?

Task sharing increases new users and reduces unmet need for family planning, increases method continuation, and improves maternal healthcare outcomes. Task sharing contributes to an increase in new contraceptive users, especially those in hard-to-reach areas and those who are underserved (e.g., adolescents and youth), thus reducing unmet need for family planning. It improves the likelihood of method continuation.1,3,9,19

Declining unmet need for family planning reduces unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and maternal deaths by nearly two-thirds.20 As expansion of family planning services increases through task sharing, the number of new users of modern methods of family planning also goes up.8,21

Task sharing helps women and communities locate and use quality family planning services, which leads to an uptick in family planning method use. Availability and access to long-acting and permanent methods of family planning are particularly enhanced by task sharing of method provision and increased referrals to highly trained cadres for permanent methods.22

Task sharing improves access and increases demand for quality family planning services.23 Task sharing brings services closer to the community and to those who are often at highest risk for unintended pregnancy and poor birth outcomes such as preterm labor, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, low birth weight, and stillbirth. Through the expansion of trained healthcare workers and the redistribution of quality services, task sharing delivers family planning services to locations and populations that were previously neglected or hard to reach.

Task Sharing Increases New Users in Family Planning

In Burkina Faso, new users for implants, IUDs, injectables, and contraceptive pills increased during the task sharing program implemented by trained CHWs and midwives. Couples using family planning services increased 183% from 2010 to 2019, with the highest change during the task sharing implementation phase.8

In Nigeria, nurses, midwives, and community health extension workers became responsible for the provision of the entire family planning program in 2014. The uptake of long-acting reversible contraceptives increased by 80% in the following four years.8

In Kenya, family planning uptake increased up to 68% in the intervention counties over a two-year period after nurses and clinical officers expanded services to include more family planning methods, such as injectables like depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA)-IM (intramuscular) and DMPA-SC (subcutaneous).9

In India, task sharing of postpartum IUD insertion with nurses improved acceptance rates with no increase in complications.15

Task sharing can expand family planning access in fragile contexts, including conflict-affected and humanitarian settings. Task sharing is part of primary action responses—preparedness, response, and recovery—to humanitarian crises. Task sharing helps staff and healthcare facilities mobilize and adapt to changes during a crisis event and in ongoing fragile settings.24

Expanding the cadres of healthcare providers increases access to services in rural communities and other hard-to-reach locations. Adolescents and other key populations are better served through provision of services in locations that are accessible to them and by healthcare workers perceived as caring and trustworthy.14,25 Task sharing can engage private sector pharmacies and drug shops through the training of pharmacists and pharmacy.26 That way local community-based providers of quality family planning services are then available to more communities, providing clients with closer locations, shorter waiting times, and flexible hours to obtain counseling, short-term family planning methods, and referrals.

Task sharing increases clients’ intention to use family planning methods to prevent or space pregnancy. Use of CHWs, auxiliary staff, nurses, and midwives to promote family planning, particularly in antenatal clinics and at community events, increases uptake of family planning for healthy timing and spacing of pregnancy, potentially improving maternal and newborn health outcomes.17 In rural and other hard-to-reach areas, task sharing and the use of CHWs not only boosts uptake but also provides communities with the information they need to increase demand for services.10,16,21,27,28

Task sharing is cost-effective. Task sharing increases both uptake and demand.8,16,21,27 It also is shown to be cost-effective and technically efficient across a wide range of healthcare areas, including primary care, HIV treatment, and service integration, in low- and middle-income countries.29–31 Contraceptive service delivery costs could be lowered by an estimated 28%—or $1.6 billion—across 128 LMICs if WHO recommendations for task sharing were put in place, according to an analysis of The Guttmacher Institute’s Adding It Up model.3 Use of a wide range of cadres for outreach, counseling, and service delivery improves efficiency and reduces salary outlays.31 Task sharing does incur additional training and supervision costs, particularly at initiation; inclusion of these costs is critical in the long-term planning for task sharing.

Task Sharing Enables Private Pharmacies in Uganda to Provide Family Planning Services

In Uganda, private drug shops in city outskirts play an important role in providing contraceptives, especially injectables like DMPA. Many clients, mainly continuing users, switched from government clinics due to fewer stock-outs and greater convenience. Overall, clients were satisfied, and private drug shops contributed significantly to the local family planning market.32

Task sharing increases client satisfaction with family planning services. Client surveys show that task sharing is associated with enhanced perception of quality, lowered client per-visit expenditure, increased geographic access to family planning services reducing travel time, and improved ability to choose a preferred provider.9,10,33 Reduced waiting time can have a significant impact on client satisfaction.34 Further, clients are more likely to establish a trusting relationship with healthcare workers who are indigenous to their areas. Community representatives described positive community attitudes toward CHWs providing short-acting family planning methods. They also reported that because of task sharing, community attitudes had changed and become more positive toward family planning use while misperceptions had decreased.35

Task sharing increases provider teamwork and collaboration across cadres, and it also contributes to job satisfaction. Through training, supportive supervision, and other proven approaches used in task sharing, healthcare workers learn to improve communication and service delivery skills while on the job, resulting in enhanced interprofessional relationships. Expanding scope of practice through task sharing, and investing in appropriate policies, supply chain management, and strong leadership for the healthcare workforce can have a positive impact on provider motivation and performance.5,6 Reports indicate that appropriately sharing family planning tasks allows higher-cadre clinicians more opportunities to use their specialized skills, reduces workload of available staff, enhances community follow-up for continuing contraception, and ensures greater technical efficiency with higher productivity from each worker.1,5,6,8 Healthcare directors report that improved management capacity for task sharing contributes to the strengthening of healthcare systems.29 Provider recognition and mechanisms for promotion can contribute to job satisfaction and retention of healthcare workers.5,6 Nearly all providers in one study in Burkina Faso stated that task sharing in family planning increased their job satisfaction.35

Task Sharing Improves Access to Family Planning Success

Task sharing contributed substantially to improved access to family planning and increased modern contraceptive prevalence rate (mCPR) in Ethiopia and Malawi.

In Ethiopia, using health extension workers, the country’s mCPR rose from 6% in 2000 to 41% in 2019, while its total fertility rate declined from 6.0 to 4.6 in the same period. The Health Extension Program brought family planning services, including implants, to remote parts of the country.8

In Malawi, mCPR dramatically increased when the country enabled community-based health surveillance assistants to provide family planning services, including DMPA-IM, in the community. This action contributed to Malawi’s increase in mCPR for married women of reproductive age from 7% in 1992 to 59% in 2015–2016, according to the Malawi Demographic and Health Survey.36

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

Tailor the task sharing approach to the local context and involve local stakeholders in program design, implementation, and evaluation. Local context is a key factor to consider in the design and implementation of a successful task sharing approach. Which specific cadres to involve is a decision that rests with national- and subnational-level decision makers. Providers and clients, including adolescents, should be involved in the design and implementation of the approach to ensure acceptance of key stakeholders. Subnational healthcare teams may build capacity for joint implementation of family planning programs, policy frameworks, and guidelines tailored to the local context.

Consider broadly based advocacy approaches to include both institutional change and individual provider support. Implementing task sharing approaches must include sustainable policy and program development as well as provider buy-in. Adapting healthcare service innovations to changing sociocultural, economic, and institutional contexts is vital for success. Building political will to introduce and sustain the task sharing approach is important, as are identifying and recruiting potential influencers to build the system and advocate for implementation. Advocacy with providers who may resist adoption of a task sharing approach is critical.

Clearly define roles and responsibilities for those included in task sharing duties. Successful implementation of task sharing requires clearly defined roles and responsibilities for both the newly designated service providers and those who are sharing their usual tasks. All cadres should fully understand expectations as well as the skills needed to promote quality care and patient satisfaction. Evidence-based standardized protocols, sufficient job aids, and formalized scope of work should be in place. Written standard protocols and job aids need to be developed, disseminated, and updated on a regular basis. A clear scope of work should be provided for each cadre, and a formal process should be in place to make the scope official. Collaboration with professional associations helps ensure that each scope of work is formalized.

Provide appropriate training, mentoring, and supportive supervision. For task sharing success, training should be emphasized, including on clinical guidelines and job aids, recordkeeping, referrals, and audits/tools to collect data. Training must include routine supervision, mentoring, and periodic and ongoing refresher training. Using digital healthcare for training of healthcare workers can be helpful for professional development and timely data collection for program planning. Inclusion of task sharing in pre-service training through university and pre-service training systems should be considered.

Update policy and regulations to support task sharing within selected cadres for family planning service provision. Successful implementation of task sharing requires clear policy guidance and regulations that support new roles and responsibilities. The Ministry of Health and other government actors must be engaged in the leadership of task sharing adoption and implementation. National and local laws and regulations that govern provision of healthcare require review and possible updating. Task sharing should be included in key national and subnational planning and regulatory documents. Country plans for task sharing for family planning should be positioned within the broader national objectives of universal health coverage and primary healthcare.

Assure adequate funding and resources. Although task sharing is a cost-saving and cost-efficient strategy, it does require dedicated funding for successful implementation.1,3,30 Training of new cadres, supportive mentoring and supervision, the sharing of key learnings, and development of training curricula and materials must be consistently included in the healthcare budget. A strategy that seeks funding commitments to create a business case to sustain task sharing implementation will support scalability and sustainability beyond the short term.

Examine digital healthcare opportunities for task sharing. Digital technologies and platforms have expanded the use of telehealth and often resulted in informal task sharing. During the COVID-19 era, digital platforms and telehealth options rapidly expanded to increase healthcare service access and use, with task sharing widening the range and level of healthcare workers who can safely deliver quality family planning services.17 Post-COVID, digital technology and telehealth are changing the landscape of service delivery, creating new ties to quality services and virtual and in-person task sharing approaches. See Digital Health HIPs to support family planning providers, systems, and social and behavior change.

Monitor and evaluate task sharing implementation using routine data collection tools and methods. Scaling up implementation of task sharing requires a firm understanding of what is working and not working. Monitoring and evaluating the adopted task sharing approach are critical to making any needed changes or updates. Using routine data collection methods on an ongoing basis assists in making implementation decisions and in documenting the successes of the approach. Client feedback should be included as a monitoring tool, and scalability and sustainability should be tracked.

Implementation Measurement and Indicators

Task sharing has demonstrated benefits in providing and receiving family planning services. The following indicators may be helpful in measuring implementation and outcomes:

- Each instance of task sharing policies, regulations, or guidelines that has been designed, adopted, updated, or implemented is tracked for family planning with leadership from the Ministry of Health.

- Number/percentage of healthcare workers who have received new or in-service training/professional development in providing quality family planning services following introduction or updating of task sharing policies and guidelines.

- Number/percentage of healthcare providers within their cadres performing family planning service tasks through task sharing in locally specified area(s).

- Number/percentage of mid-level provider cadres (e.g., nurses, midwives) employed to fill vacancies in family planning service positions.

Tools and Resources

- Guidance on Planning, Implementing and Scaling Up Task Sharing for Contraceptive Services. This guide provides the World Health Organization’s evidence-based recommendations and practical strategies along with tools and templates for planning, implementing, and scaling up task sharing contraceptive services.

- Task Sharing for Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives and Permanent Methods: A desk review. This review of seven countries assessed the extent to which they had adopted and operationalized the WHO recommendations for task sharing for family planning and identifies key challenges, barriers, and opportunities related to effective implementation of the guidelines.

- National Family Planning Guidelines in 10 Countries: How well do they align with current evidence and WHO recommendations on task sharing and self-care? This analysis documents the extent to which 10 countries adopted policies, service delivery guidelines, or other documents in line with current evidence and WHO guidelines on task sharing and self-care for family planning.

- Towards Achieving the Family Planning Targets in the African Region: A rapid review of task sharing policies. This study explores the evidence of the status, challenges, success, and impact of implementation of task sharing for family planning in five African countries.

- HOT4: A toolkit for optimizing HRH to deliver more efficient services. This set of three tools helps human resources for health (HRH) planners, including facility-level managers, optimize HRH for various services through task sharing and differentiated service delivery models.

Priority Research Questions

- How do the varied policy and regulatory factors relating to task sharing (such as drug regulations, provider scopes of work, and clinical guidelines produced by other ministry units) facilitate or inhibit full implementation of task sharing in family planning?

- How is cost saving and technical efficiency for family planning enhanced or reduced through task sharing in low- and middle-income countries?

- What factors are related to family planning task sharing successes, barriers, and effectiveness of using mid-level cadres (such as nurses, midwives, associate clinicians, pharmacists, and pharmacy assistants) to deliver a range of services?

- How does task sharing support family planning service uptake and continuity in fragile settings (such as security-challenged areas and hard-to-reach populations and geographies)?

- How do multilevel governance structures (national, subnational, and community) influence the successful implementation and sustainability of task sharing for family planning services?

- What are the most effective strategies for stakeholder engagement, including professional associations, community leaders, and private sector actors, in scaling up task sharing for family planning in diverse contexts?

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs).Task Sharing: Increasing healthcare workforce efficiency to expand access to and use of quality family planning services. Washington, DC: HIPs Partnership; 2025 December. Available from: https://fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/task-sharing/.

Acknowledgements

This HIPs enhancement brief was written by Jutomue Doetein (Independent), Ebony Fontenot (JSI Nigeria), Gathari Ndirangu Gichuhi (Jhpiego), Sameh Madian (DKT International Egypt), Jimmy Nzau (Pathfinder International), Sadia Parveen (USAID), Ellen Peprah (NIHR Global Health Research Centre for the Control of NCDs in West Africa), Asma Qureshi (Independent), Vinit Sharma (UNFPA), Gladys Tetteh-Yeboah (USAID/Ghana), and Linda Cahaelen (HIPs writer). It was previously a Strategic Planning Guide, published in 2019, available here: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/previous-brief-versions/.

This HIPs enhancement brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Moazzam Ali (WHO). Maria Carrasco (USAID), Ginette Hounkanrin (Pathfinder International), Emeka Nwachukwu (USAID), Medha Sharma (Visible Impact), Sara Stratton (Palladium), and others who commented via the HIPs website.

The World Health Organization Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception.

References

1. World Health Organization. Task Sharing to Improve Access to Family Planning/Contraception, Summary Brief. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-RHR-17.20.

2. World Health Organization. WHO Health Workforce Support and Safeguards List 2023. 1st ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240069787.

3. World Health Organization. Guidance on Planning, Implementing and Scaling Up Task Sharing for Contraceptive Services. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025. Accessed September 30, 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240111486.

4. High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Family Planning in Humanitarian Settings: A Strategic Planning Guide. Washington, DC: Family Planning 2020; 2020 September. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/guides/family-planning-in-humanitarian-settings/.

5. World Health Organization, PEPFAR, UNAIDS. Task Shifting: Global Recommendations and Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2007/20071231_ttr_taskshifting_en.pdf.

6. Coales K, Jennings H, Afaq S, et al. Perspectives of Health Workers Engaging in Task Shifting to Deliver Health Care in Low-and-Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Global Health Action. 2023;16(1):2228112. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10337489/.

7. Millogo T, Kouanda S, Tran NT, et al. Task Sharing for Family Planning Services, Burkina Faso. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2019;97(11):783–788. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6802696/.

8. Ouedraogo L, Habonimana D, Nkurunziza T, et al. Towards Achieving the Family Planning Targets in the African Region: A Rapid Review of Task Sharing Policies. Reproductive Health. 2021;18(1). Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-020-01038-y.

9. Ouedraogo L, Mollent O, Joel G. Effectiveness of Task Sharing and Task Shifting on the Uptake of Family Planning in Kenya. Advances in Reproductive Sciences. 2020;08(04):209–220. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=103607.

10. Douthwaite M, Ward P. Increasing Contraceptive Use in Rural Pakistan: An Evaluation of the Lady Health Worker Programme. Health Policy and Planning. 2005;20(2):117–123. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/heapol/article/20/2/117/568789.

11. UNFPA Pakistan, UK Aid. Policy Brief, Task Shifting and Task Sharing for Family Planning in Pakistan: Progress, Challenges and Way Forward. Islamabad: UNFPA Pakistan, UK Aid; 2020. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://pakistan.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/task_shifting_task_sharing_policy_brief_v4-2020.pdf.

12. Phillips JF, Hossain MB, Simmons R, Koenig MA. Worker-Client Exchanges and Contraceptive Use in Rural Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning. 1993;24(6):329. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2939243.

13. Phillips JF, Hossain MB, Arends-Kuenning M. The Long-term Demographic Role of Community-Based Family Planning in Rural Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning. 1996;27(4):204. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2137954.

14. High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Adolescent-Responsive Contraceptive Services: Institutionalizing Adolescent-Responsive Elements to Expand Access and Choice. HIPs Partnership; 2021 March. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/adolescent-responsive-contraceptive-services.

15. Bhadra B, Burman SK, Purandare CN, Divakar H, Sequeira T, Bhardwaj A. The Impact of Using Nurses to Perform Postpartum Intrauterine Device Insertions in Kalyani Hospital, India. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2018;143(S1):33–37. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijgo.12602.

16. Tilahun Y, Lew C, Belayihun B, Lulu Hagos K, Asnake M. Improving Contraceptive Access, Use, and Method Mix by Task Sharing Implanon Insertion to Frontline Health Workers: The Experience of the Integrated Family Health Program in Ethiopia. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2017;5(4):592–602. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/5/4/592.

17. Mickler AK, Carrasco MA, Raney L, Sharma V, May, AV, Greaney J. Applications of the High Impact Practices in Family Planning during COVID-19. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters. 2021;29(1):1881210. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/26410397.2021.1881210.

18. Population Reference Bureau (PRB). Pandemic Prompts New Digital Health Solutions for Family Planning. Washington, DC: PRB; 2022 February. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.prb.org/articles/pandemic-prompts-new-digital-health-solutions-for-family-planning/.

19. Hernandez JH, LaNasa KH, Koba, T. Task-Shifting and Family Planning Continuation: Contraceptive Trajectories of Women Who Received Their Method at a Community-Based Event in Kinshasa, DRC. Reproductive Health. 2023;20(1). Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-023-01571-6.

20. The Guttmacher Institute. Provision of Essential Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Would Reduce Unintended Pregnancies, Unsafe Abortions and Maternal Deaths by About Two-Thirds. News release. July 28, 2020. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/news-release/2020/provision-essential-sexual-and-reproductive-health-care-would-reduce-unintended.

21. Solanke BL, Oyediran OO, Awoleye AF, et al. Do Health Service Contacts With Community Health Workers Influence the Intention to Use Modern Contraceptives Among Non-Users in Rural Communities? Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study in Nigeria. BMC Health Services Research. 2023;23(24). Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://chwcentral.org/wp-content/uploads/12913_2023_Article_9032.pdf.

22. Ngo TD, Nuccio O, Pereira SK, Footman K, Reiss K. Evaluating a LARC Expansion Program in 14 Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Service Delivery Model for Meeting FP2020 Goals. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2016;21(9):1734–1743. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10995-016-2014-0.

23. Nabhan A, Kabra R, Ashraf, A, et al. Implementation Strategies, Facilitators, and Barriers to Scaling Up and Sustaining Demand Generation in Family Planning: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. BMC Women’s Health. 2023;23(1). Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-023-02735-z.

24. Women’s Refugee Commission, Inter-Agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises, FP2030. Contraceptive Services in Humanitarian Settings and in the Humanitarian-Development Nexus: Summary of Gaps and Recommendations from a State-of-the-Field Landscaping Assessment. New York City: Women’s Refugee Commission; 2021 March. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/FP-In-Humanitarian-Settings-In-The-Humanitarian-Development-Nexus_Summary.pdf.

25. Garney WR, Flores SA, Garcia KM, Panjwani S, Wilson KL. Adolescent Healthcare Access: A Qualitative Study of Provider Perspectives. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2024;15(15). Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/21501319241234586.

26. Peterson J, Brunie A, Diop I, Diop S, Stanback J, Chin-Quee DS. Over the Counter: The Potential for Easing Pharmacy Provision of Family Planning in Urban Senegal. Gates Open Research. 2019;2:29. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6600082/.

27. Haver J, Brieger W, Zoungrana J, Ansari N, Kagoma J. Experiences Engaging Community Health Workers to Provide Maternal and Newborn Health Services: Implementation of Four Programs. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2015;130:S32–S39. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0020729215001356.

28. Masiano SP, Green TL, Dahman B, Kimmel AD. The Effects of Community-Based Distribution of Family Planning Services on Contraceptive Use: The Case of a National Scale-Up in Malawi. Social Science & Medicine. 2019;238:112490. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953619304836.

29. Seidman G, Atun R. Does Task Shifting Yield Cost Savings and Improve Efficiency for Health Systems? A Systematic Review of Evidence from Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. Human Resources for Health. 2017;15(1). Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12960-017-0200-9.

30. The Local Health System Sustainability Project (LHSS) Under the USAID Integrated Health Systems IDIQ. Catalog of Approaches to Improve Technical Efficiency in Health Systems. Rockville, MD: USAID; 2022 September. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20240604151225/https://www.lhssproject.org/sites/default/files/resource/2023-04/LHSS_Core16_Catalog%20of%20Approaches%20to%20Improve%20Technical%20Efficiency%20in%20Health%20Systems_Y4_508C.pdf.

31. Vaughan K, Kok MC, Witter S, Dieleman M. Costs and Cost-effectiveness of Community Health Workers: Evidence from a Literature Review. Human Resources for Health. 2015;13(71). Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12960-015-0070-y.

32. Akol A, Chin-Quee DS, Wamala-Mucheri P, Namwebya JH, Mercer SJ, Stanback J. Getting Closer to People: Family Planning Provision by Drug Shops in Uganda. Global Health Science and Practice. 2014;13;2(4):472–481. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/2/4/472.

33. Arends-Kuenning M. How Do Family Planning Workers’ Visits Affect Women’s Contraceptive Behavior in Bangladesh? Demography. 2001;38(4):481–496. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://read.dukeupress.edu/demography/article-abstract/38/4/481/170488/How-do-family-planning-workers-visits-affect-women.

34. Geta T, Awoke N, Lankrew T, Elfos E, Israel E. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Client Satisfaction with Family Planning Service Among Family Planning Users in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. BMC Women’s Health. 2023;23(1). Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-023-02300-8.

35. Chin-Quee DS, Ridgeway K, Onadja Y, et al. Evaluation of a Pilot Program for Task Sharing Short and Long-Acting Contraceptive Methods in Burkina Faso. Gates Open Research. 2020;3:1499. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://gatesopenresearch.org/articles/3-1499.

36. National Statistical Office and ICF. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015–16. Zomba, Malawi, and Rockville, Maryland: National Statistical Office and ICF; 2017. Accessed September 2, 2025. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR319/FR319.pdf.