Family Planning Vouchers: A tool to boost contraceptive method access and choice

Background

Health care vouchers are paper or electronic referral coupons that clients can take to an accredited health care provider in exchange for health care services. They are used as a service purchasing mechanism and programmatic tool to improve equitable access and increase the use of key health products and services.1 Vouchers are a form of results-based financing, a type of health system reform which includes payment or non-monetary transfers after services have been delivered and verified.2,3 Payment to service providers is only issued when the services have been delivered in accordance with the voucher program standards and guidelines.

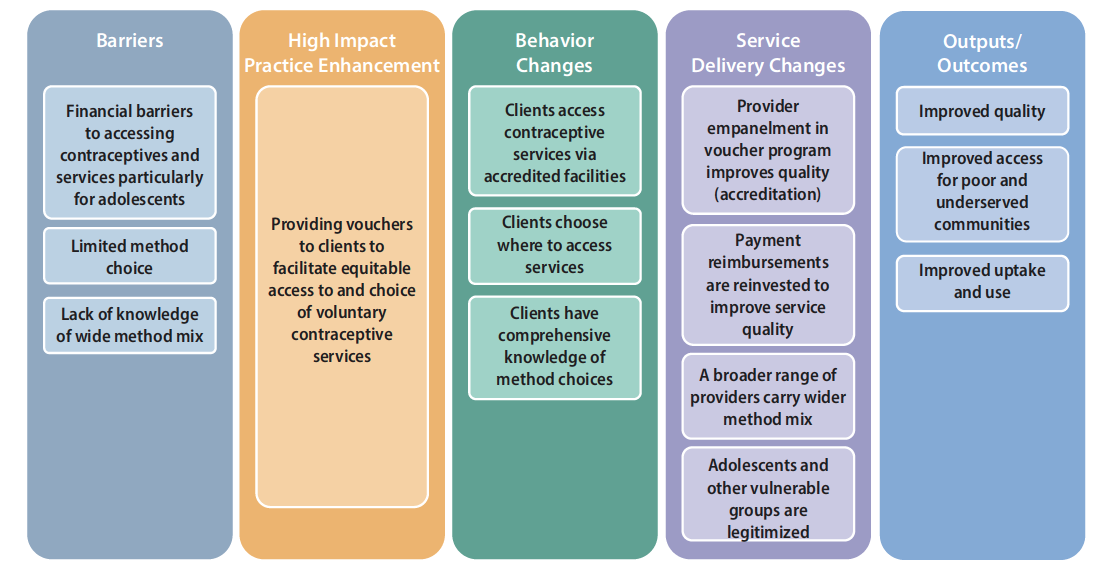

In settings where potential clients must pay for contraceptive services and/or methods, individuals (e.g., adolescents) may face financial barriers that restrict their ability to access and use some methods. Vouchers can reduce these financial barriers and facilitate client access to more contraceptive options.4 Vouchers that focus on specific population groups help ensure subsidies reach individuals who may be less likely to have access to and ability to use family planning services and products. Voucher programs can be designed to improve client knowledge of contraceptive method options and inform potential clients where and when they can access services. Vouchers can also support providers to improve the quality of their services through accreditation and to expand the range of contraceptive methods available.

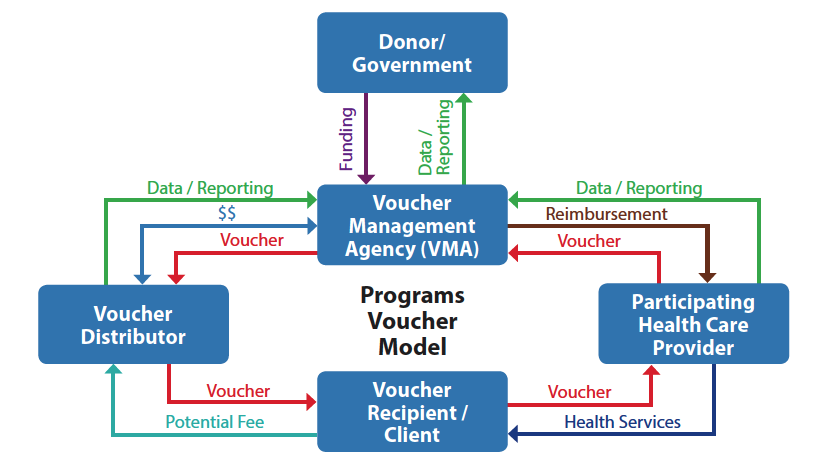

Figure 1 depicts an illustrative example of how contraceptive voucher programs work. Voucher programs typically include a fund processing body (voucher management agency), and an independent monitoring and oversight body (e.g., third-party verification agents or a governance board).5-7 Voucher programs typically contract private and/or public providers who have met quality standards, and they engage community organizations to promote the program and distribute or sell vouchers to eligible, interested clients.6,8

This brief discusses the potential contributions of vouchers to enhancing the quality and voluntary use of contraceptive services, outlines key issues for planning and implementation, and identifies knowledge gaps. Vouchers have been identified as a HIP enhancement by the HIP technical advisory group. A HIP enhancement is a tool or approach that is not a standalone practice, but is often used in conjunction with HIPs to maximize the impact of HIP implementation or increase the reach and access for specific audiences. The intended purpose and impact of enhancements are focused, and therefore the evidence base and impact of a HIP enhancement is subjected to different standards than a HIP. While there is some evidence and programmatic experience implementing voucher programs, more research and documentation is needed to better understand the potential and limitations of this approach. For more information about HIPs, see https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/overview.

How Can Vouchers Enhance HIPs?

Vouchers can support implementation of a number of HIPs (Table 1). In general, they can help family planning programs remove barriers and expand client access to more contraceptive options including those that may be too expensive or otherwise difficult for clients to access. The potential impact of voucher programs at the population level is determined by the size of the target population group, distribution coverage of the program, and client uptake of vouchers. There are few studies that demonstrate a community-level impact on the modern contraceptive prevalence rate (mCPR) of voucher programs. Studies in Jordan and Pakistan have documented significant community-level effects of voucher programs on mCPR,9-11 but other studies in Cambodia, Kenya, and Pakistan have found no statistically significant change in contraceptive prevalence in intervention communities.12-15

Vouchers facilitate client access to more contraceptive options. Even when family planning services are presumed to be free at point of care, subtle financial barriers may exist. For example, a survey of seven countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, where family planning is largely mandated free of charge to clients in public-sector facilities, found that client out-of-pocket expenditure was a significant source of family planning financing.16 A systematic review concluded that “vouchers can expand client choice by reducing financial barriers to contraceptive services and make private providers an option for disadvantaged clients previously restricted by cost.”17

Evidence from voucher programs consistently shows that when a voucher program reduces or removes the client’s cost for provider-dependent methods, use of provider-dependent methods increases while use of other methods either remains the same or increases.9,12,18 Vouchers covering specific methods can promote method choice and reduce method-specific barriers, such as shortages of competent providers, lack of commodities or equipment, and/or limited client demand. In Pakistan, programs offered free vouchers for voluntary IUD insertion and removal by private social franchise clinics and independent, community nurse-midwives to interested married women who met the criteria for poverty to offset the cost of obtaining an IUD. Voluntary IUD uptake increased in communities served by these voucher programs while use for all other modern methods remained the same or increased.9,14

| HIPs | Vouchers enhance the practice by … | Country Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting integrated services by targeting single or multiple related health care services in addition to voluntary family planning services. | A voucher program in Yemen covered both maternity and family planning services19,20 while in India, it included antenatal care, delivery, postnatal care, and family planning services.21 | ||

| Supporting client-centered access to contraceptive products and services, including adolescent-friendly contraceptive services, through preferred and convenient service delivery points including the private sector. |

In Kenya, voucher holders could seek services at their choice of participating private, public, and/or nonprofit clinics.22,23

In Madagascar, a voucher program invested in building capacity of private franchised facilities to offer services for sexually transmitted infections and family planning and to serve youth.24 |

||

| Disseminating key information about contraceptives, services, and how to access them, as well as addressing other nonfinancial barriers. | In Pakistan, a voucher program relied on community outreach workers to raise awareness and counsel about family planning to potential clients.11 | ||

| Improving efficiency of the use of domestic resources by targeting public funding of family planning to beneficiaries facing barriers to access, helping to overcome challenges for clients who are inclined to seek care, but lack motivating information.. | Experience with the Vouchers for Health Programme (Kenya) is helping national policy makers prepare for a national social health insurance program.5 World Bank funds to countries have supported implementation of voucher programs in countries like Bangladesh, India, and Zimbabwe. |

Vouchers improve access to contraceptives for key population groups. A review of 24 NGO-supported voucher programs across 11 countries in Africa and Asia between 2005 and 2015 found that most programs were successful in reaching subgroups, such as the poor and young consumers (under 25 years), although this outcome depended on the targeting approach and how beneficiaries were identified.19

In rural India, a voucher program contributed to an increase in mCPR among women living below the poverty line, from 33% to 43%.21 Similar results were noted from studies in Pakistan.14 From 2013 to 2014 in Madagascar, a social franchising network offered vouchers for family planning and sexually transmitted infection (STI) services, in which 96% of clients were 20 years old or younger.24 In Nicaragua, adolescents who obtained vouchers had 3.1 higher odds of using participating health centers compared to those who did not receive vouchers. Additionally, sexually active adolescents who received vouchers had twice the odds of using modern contraception, and 2.5 higher odds of reporting condom use at last sex compared with adolescents who did not obtain vouchers.25 Vouchers can also reach other disadvantaged groups, such as those with little or no education. For example, in Uganda, where only 23% of women with no education and 34% of women with a primary education use a modern method,26 a voucher program facilitated family planning access for 330,826 women, 79% of whom had no education or only primary education.18

Vouchers facilitate access to private providers. Some groups, like unmarried youth, may prefer accessing contraceptive services through private providers due to convenience, a perception of higher quality and greater confidentiality than in the public sector, or other factors.27 Vouchers can expand access to the private sector for groups who may face access challenges due to prohibitive user fees, such as low-income individuals or adolescents.28 In addition, vouchers can enable access to health services in private facilities when public facilities are unable to provide services, including in fragile states.9,14,20,29 Engaging the private sector can also expand geographic coverage and/or access to a wider choice of contraceptive methods.30

Vouchers can drive service quality improvements. Two systematic reviews concluded that voucher programs can improve the quality of service provision.31,32 A voucher accreditation process establishes standards of care and assists in developing the capacity of the voucher program to measure and monitor the quality of health services. Voucher payments offer providers a steady flow of income that can be reinvested in improving services. For example, in Kenya 67% to 89% of providers used revenue from voucher payments to improve infrastructure, buy equipment or drugs and supplies, hire new or pay existing staff, or create patient amenities.33 Voucher program health care providers in Nicaragua had better clinical knowledge, improved provider practices, and, to a lesser extent, improved provider attitudes toward adolescent use of family planning and STI services compared with providers not involved in the voucher program.34,35 Client satisfaction was significantly higher among adolescents using vouchers than among those without vouchers.34 A study in Pakistan also noted improvement in quality standards in the provision of family planning information, services, and commodities, including the quality of counseling services, the method mix from which clients could choose, respect for clients’ privacy, and client satisfaction.36

How to do it: Tips from Implementation Experience

- Invest in voucher distribution. Voucher distribution involves identifying members of the client population in a way that is cost-effective, respectful of beneficiary confidentiality and needs, and timely for the beneficiary. Consider working with existing digital platforms or community structures, such as community health workers, particularly when trying to reach youth who may face social barriers to accessing services and adopting contraception. Remuneration to CHWs should not incentivize promotion of particular contraceptive methods and can be mainstreaned into a well-rounded financial and non-financial remuneration strategy. Distributors need to be adequately trained using a client-centered approach that supports voluntary choice. While it can be challenging to implement, regular supportive supervision of community-level distribution is essential. Client and provider-facing digital technologies, where appropriate such as facilitating client health education, client identification, provider payments, provider support or client follow up, may help.

- Develop clear, feasible eligibility criteria. Poverty assessment tools are typically in the form of questionnaires and are used to assess eligibility for vouchers based on wealth assets (e.g. EquityTool.org).37,38,39 Some countries, like India, use an established standard, such as the “below poverty line” or poverty card. Other programs demark geographic areas as poor or vulnerable communities, called geographic targeting. Debate is ongoing about means testing, which can be expensive, time-consuming, and intrusive, and geographic targeting, which is less accurate but simpler and at lower cost.40,41 Voucher programs are increasingly opting for geographic targeting alongside training of voucher distributors to identify eligible clients.

- Vouchers should be designed and promoted using social and behavior change principles and best practices. Vouchers constitute a key component of comprehensive demand generation that improves knowledge of and access to contraceptive methods among disadvantaged audience groups. Promotion of voucher programs should be integrated into broader family planning campaign channels (e.g., mass media, digital, print, outreach, community forums) and messages to maximize reach. A randomized controlled experiment tested whether vouchers for free contraception, provided with and without behavioral “nudges,” could increase modern contraceptive use during the postpartum period. At six months postpartum, the voucher combined with an SMS reminder increased reported use of modern contraceptive methods by 25 percentage points compared with the comparison group. Estimated impacts of the voucher alone were not statistically significant.42

- Consider whether to use paper vouchers or e-vouchers. As rates of mobile phone use increase, interest in electronic vouchers grows. However, recent experiences suggest caution in relying on e-vouchers because mobile phones may be owned by a household rather than an individual; both distributors and clients require reliable network coverage; and if contraceptive use is clandestine, messages relating to family planning may place beneficiaries in danger, make them uncomfortable, or not reach the intended beneficiary. In Madagascar, adolescents either lacked access to a mobile phone or were concerned about confidentiality when e-vouchers were sent by phone. After adding a paper voucher option, voucher distribution increased rapidly.24 The opportunity for digitizing some aspects of voucher distribution and use is growing as usage of mobile phones and digital platforms continues to expand and be adapted by wider swaths of LMIC populations.

- Choose participating health care providers carefully, using a clear accreditation process. Prior to launching a voucher program, managers should map and assess potential health care providers to ensure the program is geographically accessible to intended beneficiaries and meets quality and managerial requirements. In addition to meeting standards for quality service delivery and expectations for providing nonjudgmental care to clients, providers must be able to collect, organize, and manage the vouchers they receive to ensure that the voucher management agency can verify services rendered and accurately pay the facility/provider. Providers will need to consider their own cost and revenue estimates to decide whether to participate in the voucher program. Program managers must conduct regular monitoring to ensure requirements and standards of the voucher program are upheld. When providers do not comply with the terms of their voucher agreement, managers typically sanction non-compliant providers early and publicly to encourage other providers to comply. Partnering with social franchising networks, in which health care providers are typically accredited and operating under clear service requirements, can facilitate the identification and enrollment of qualified providers.

- Determine how voucher reimbursements will be used when working with public-sector providers. Public facilities may not be able to receive direct payments from the voucher management agency for voucher services rendered or decide how to use the revenue for improvements at the facility level; governments must determine how voucher revenue will be used in line with their domestic public financing goals. Public-sector providers may also lack full autonomy to provide services according to the requirements of the voucher program, including the ability to hire additional medical staff or direct resources to facility-level repairs, supply needs, or other improvements.6 In Cambodia, the voucher program was able to negotiate with the government to make payments, or a portion of payments, directly to facilities. In Kenya, some voucher providers in the public sector have been able to invest a growing proportion of their voucher income into improving service quality.6

- Offer a service package that is responsive to client demand. Including a range of services in the voucher program, typically maternity care (immediate postpartum family planning) or STI diagnosis and treatment services,6 in addition to family planning can facilitate confidentiality and better meet the health needs of beneficiaries. This may be particularly important for adolescents and unmarried women. Counseling, any desired follow-up, and voluntary removals for long-acting reversible contraceptives should be covered in contraceptive voucher services, to ensure client-centered care and avoid prohibitive costs to clients.

- Include safeguards to ensure voluntary, contraceptive choice. As any program involving financial mechanisms or performance-based incentives, monitoring should be in place so that voucher programs do not inadvertently incentivize inappropriate provider behaviors, such as inflating client numbers or promoting provision of one contraceptive method over another.3 If provider reimbursements are differentiated by service or contraceptive method, ensure that rates reflect the time, commodities, and skill level required for that service in order to avoid unintended incentives.3 If a voucher program aims to increase access to specific methods, such as provider-dependent methods, confirm that other methods are also readily available and that providers support voluntary, client-centered family planning service provision. Programs should make sure the cost of a voucher is roughly the same as the cost of obtaining another contraceptive method and that voucher distribution agents provide other contraceptives or refer clients to the closest service point that offers the method of choice.

- Careful attention should be given to estimating the cost of managing and implementing a voucher program, including costs for training, accreditation, supervision, administration, and other key inputs. These costs are highly variable depending on design, size, content, and context of the program. A rural voucher program in Pakistan with private sector social franchise clinics cost approximately US$3.3 million.43 Kenya’s safe motherhood and family planning voucher programs were budgeted at 6.5 million Euros between 2006 and 2008.5

- Design programs to promote accountability. Voucher management agencies or other voucher governing bodies are charged with putting in place mechanisms to prevent, detect, and manage fraud, should it occur in the program. The physical record of service provision, in most cases a uniquely numbered paper voucher, simplifies auditing, giving these programs a strong accountability mechanism. Separation of the voucher management agency function from participating health care providers can increase transparency, allow for independent verification of service delivery, and help curb informal payments. Results verification and routine voucher data analysis, including tracking trends in vouchers distributed and claims made and use of spot checks, are used to counteract fraud.

Priority Research Questions

These research questions, reviewed by the HIP technical advisory group, reflect the prioritized gaps in the evidence base specific to the topics reviewed in this brief and focus on the HIP criteria.

- What are the costs of voucher programs, including voucher management, fraud detection, etc.?

- Can selected characteristics of vouchers and voucher programs increase voucher redemption? (e.g., expiration dates, free vs. priced, single vs. multiple method)

Voucher programs work best where:

- Financial and other access barriers restrict access to contraceptives among a specific underserved client group.

- Eligible clients can be accurately identified and effectively reached.

- Adequate resources exist to implement vouchers at sufficient scale and over a long enough period of time to justify a fully functional voucher management system.

- There is at least one, but optimally more, providers with the potential capacity to provide contraceptive services, including voluntary long-acting reversible contraceptives and permanent methods.

- Robust supply-side mechanisms are in place to build and assure service quality, including sanctions for providers who do not meet quality standards.

Factors contributing to failure of voucher programs:

- Poor management of voucher distributors and inadequate attention to voucher distribution and marketing.

- Provider reimbursement is not set appropriately to make up for the costs of delivering services.

- Providers are not reimbursed in a timely manner for voucher services rendered.

- Definition of what is included in the voucher service package is not clear to the provider and/or the client.

- Ability to verify voucher service delivery is limited.

- Poor design of voucher program such that target groups are not optimally reached or services covered are not those desired by target groups.

It is recommended that programs implementing family planning vouchers include the following indicators:

- Percent of vouchers distributed that are redeemed by target groups

A Guide to Competitive Vouchers in Health: Identifies the advantages of competitive voucher schemes in delivering subsidies; describes the circumstances under which they are superior to other subsidy mechanisms; and explains how to design, implement, monitor, and evaluate a voucher scheme. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/179801468324054125/A-guide-to-competitive-vouchers-in-health

E-Vouchers for Family Planning: Advantages, Challenges and Trends: Mobile Finance to Reimburse Sexual and Reproductive Health Vouchers in Madagascar: Compares strengths and weaknesses of innovative approaches using digital technology relative to traditional paper voucher initiatives and offers best practices. https://www.

shopsplusproject.org/resource-center/e-vouchers-family-planning-advantages-challenges-and-trends

Reproductive Health Vouchers: From Promise to Practice: Presents key implementation lessons drawn from Marie Stopes International’s experience in setting and managing reproductive health voucher programs in various settings. https://healthmarketinnovations.org/sites/default/files/Reproductive%20Health%20Vouchers%20from%20promise%20to%20practice_0.pdf

Vouchers for Health: A Focus on Reproductive Health and Family Planning Services: Discusses key aspects of voucher programs, elements for assessing the feasibility of a prospective program, and steps for designing and implementing a program where feasible. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADI574.pdf

Search Strategy

To compile the list of documents meeting inclusion criteria, a literature search was conducted using bibliographic databases and hand searching of online websites for journal and grey literature. Evidence relevant to how vouchers can be used to enhance High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs) was systematically analyzed. The period of review focused on documents published between 2012 and January 2018–after the previous HIP brief on Vouchers was developed.

For more information, download the Methods for literature search, information sources, abstraction and synthesis document.

References

- Ahmed S, Khan MM. Is demand-side financing equity enhancing? Lessons from a maternal health

voucher scheme in Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(10):1704-1710. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.031 - Musgrove P. Financial and other rewards for good performance or results: A guided tour of concepts and terms and a short glossary. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2011. https://www.rbfhealth.org/sites/rbf/files/RBFglossarylongrevised_0.pdf. Accessed April 18, 2019.

- Eichler R, Wright J, Bellows B, Cole M, Boydell V, Hardee K. Strategic purchasing to support voluntarism, informed choice, quality and accountability in family planning: Lessons from results-based financing. Rockville, MD: Health Finance & Governance Project, Abt Associates Inc.; 2018. https://www.hfgproject.org/?download=25655. Accessed April 18, 2019.

- Bashir H, Kazmi S, Eichler R, Beith A, Brown E. Pay for performance: Improving maternal health services in Pakistan. Bethesda, MD: Health Systems 20/20 Project, Abt Associates Inc.; 2009. https://www.hfgproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Pay-for-Performance-Improving-Maternal-Health-Services-in-Pakistan.pdf. Accessed April 18, 2019.

- Abuya T, Njuki R, Warren CE, Okal J, Obare F, Kanya L, et al. A policy analysis of the implementation of a Reproductive Health Vouchers Program in Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:540. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-540

- Grainger CG, Gorter AC, Okal J, Bellows B. Lessons from sexual and reproductive health voucher program design and function: A comprehensive review. Int J Equity Health. 2014; 13(33):1-25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-13-33

- Ali M, Farron M, Azmat SK, Hameed W. The logistics of voucher management: the underreported component in family planning voucher discussions. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:683-690. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S155205

- Bellows B, Bajracharya A, Bulaya C, Inambwae S. Family planning vouchers to improve delivery and uptake of contraception in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Lusaka, Zambia: Population Council; 2015. http://healthmarketinnovations.org/sites/default/files/Family%20Planning%20Vouchers%20to%20Improve%20Delivery%20and%20Uptake%20of%20Contraception%20in%20Low%20and%20Middle%20Income%20Countries-A%20Systematic%20Review.pdf. Accessed April 18, 2019.

- Azmat SK, Shaikh BT, Hameed W, Mustafa G, Hussain W, et al. Impact of social franchising on

contraceptive use when complemented by vouchers: a quasi-experimental study in rural Pakistan.

PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74260. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074260 - El-Khoury M, Thornton R, Chatterji M, Kamhawi S, Sloane P, Halassa M. Counseling women and couples on family planning: A randomized study in Jordan. Stud Fam Plann. 2016; 47(3). http://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.69

- Ali M, Azmat SK, Hamza HB, Rahman MM, Hameed Are family planning vouchers effective in increasing use, improving equity and reaching the underserved? An evaluation of a voucher program in Pakistan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:200. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4027-z

- Bajracharya A, Veasnakiry L, Rathavy T, Bellows B. Increasing uptake of long-acting reversible contraceptives in Cambodia through a voucher program: Evidence from a difference-in-differences analysis. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4(Suppl 2):S109-S121. http://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00083

- Obare F, Warren C, Njuki R, et al. Community-level impact of the reproductive health vouchers programme on service utilization in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28(2):165-175. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czs033

- Azmat SK, Hameed W, Hamza HB, Mustafa G, Ishaque M, et al. Engaging with community-based public and private mid-level providers for promoting the use of modern contraceptive methods in rural Pakistan: Results from two innovative birth spacing interventions. Reprod Health. 2016; 13(1):25. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0145-9

- Agha S. Changes in the proportion of facility-based deliveries and related maternal health services among the poor in rural Jhang, Pakistan: Results from a demand-side financing intervention. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(57):1-12. http://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-10-57

- Fagan T, Dutta A, Rosen J, Olivetti A, Klein K. Family planning in the context of Latin America’s Universal Health Coverage Agenda. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(3):382-398. http://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00057

- Bellows B, Bulaya C, Inambwae S, Lissner CL, Ali M, Bajracharya A. Family planning vouchers in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Stud Fam Plann. 2016;47(4):357-370. http://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12006

- Bellows B, Mackay A, Dingle A, Tuyiragize R, Nnyombi W, Dasgupta A. Increasing contraceptive access for hard-to-reach populations with vouchers and social franchising in Uganda. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(3):446-455. http://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00065

- Eva G, Quinn A, Ngo TD. Vouchers for family planning and sexual and reproductive health services: A review of voucher programs involving Marie Stopes International among 11 Asian and African countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;130(S3):E15-E20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.06.023

- Boddam-Whetham L, Gul X, Al-Kobati E, Gorter AC. Vouchers in fragile states : Reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception in Yemen and Pakistan. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4(Suppl 2):S94-S108. http://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00308

- IFPS Technical Assistance Project (ITAP). SAMBHAV: Vouchers make high-quality reproductive health services possible for India’s poor. Gurgaon, Haryana:: Futures Group, ITAP; 2012. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnadz573.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Janisch CP, Albrecht M, Wolfschuetz A, Kundu F, Klein S. Vouchers for health: A demand side output‐based aid approach to reproductive health services in Kenya. Global Public Health. 2010;5(6):578–594. http://doi.org/10.1080/17441690903436573

- Bellows N. Vouchers for reproductive health care services in Kenya and Uganda. 2012. https://www.kfw-entwicklungsbank.de/Download-Center/PDF-Dokumente-Diskussionsbeitr%C3%A4ge/2012_03_Voucher_E.pdf Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Burke E, Gold J, Razafinirinasoa L, Mackay A. Youth voucher program in Madagascar increases access to voluntary family planning and STI services for young people. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(1):33-43. http://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00321

- Meuwissen LE, Gorter AC, Knottnerus AJ. Impact of accessible sexual and reproductive health care on poor and underserved adolescents in Managua, Nicaragua: A quasi-experimental intervention study. J Adolesc Health. 2006a;38(1):56.e1-56.e9. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.01.009

- Uganda. Bureau of Statistics, ICF. DHS Program. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Kampala, Uganda and Rockville, MD: 2018. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR333/FR333.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Bradley SE, Shiras T. Sources for family planning in 36 countries: Where women go and why it matters. Rockville, MD: Abt Associates, Sustaining Health Outcomes through the Private Sector Plus Project; 2020. https://www.shopsplusproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/Sources%20for%20Family%20Planning%20in%2036%20Countries-Where%20Women%20Go%20and%20Why%20it%20Matters.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2020.

- Health Policy Initiative. Targeting resources and efforts to the poor: Implementing a voucher scheme in India. Washington, DC: USAID | Health Policy Initiative, Task Order 1; 2010. https://www.healthpolicyplus.com/archive/ns/pubs/hpi/1404_1_7_3_Targeting_Resources_to_the_Poor_Voucher_acc.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Grainger CG, Gorter AC, Al-Kobati E, Boddam-Whetham L. (2017). Providing safe motherhood services to underserved and neglected populations in Yemen: the case for vouchers. J Int Humanitarian Action. 2017:2:6. http://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-017-0021-4

- Mishra AK, Singh S, Sharma S, Sharma S, Singh S, Dikshit M. Does demand side financing help in better utilization of family planning and MCH services? Evidence from rural Uttar Pradesh, India. Presented at the 2011 International Conference on Family Planning, Senegal, 2011 Nov 29 – Dec 2. Dakar, Senegal. http://fpconference.org/2011/wp-content/uploads/FPConference2011-Agenda/447-mishra-does_demand_side_financing_help_in_better_utilization-3.3.06.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Bellows NM, Bellows BW, Warren C. Systematic Review: The use of vouchers for reproductive health services in developing countries: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(1):84-96. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02667.x

- Brody CM, Bellows N, Campbell M, Potts M, The impact of vouchers on the use and quality of health care in developing countries: a systematic review. Glob Public Health. 2013; 8(4):363-88. http://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2012.759254

- Arur A, Gitonga N, O’Hanlon B, Kundu F, Senkaali M, Ssemujju R. Insights from innovations: lessons from designing and implementing family planning/reproductive health voucher programs in Kenya and Uganda. Bethesda, MD: Private Sector Partnerships-One Project, Abt Associates; 2009. https://www.shopsplusproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/5361_file_FINAL_FP_Voucher_Innovations.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Meuwissen LE, Gorter AC, Kester ADM & Knottnerus JA. Does a competitive voucher program for adolescents improve the quality of reproductive health care? A simulated patient study in Nicaragua. BMC Public Health. 2006b;6:204. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-204

- Meuwissen LE, Gorter AC, Kester AD, Knottnerus JA. Can a comprehensive voucher programme prompt changes in doctors’ knowledge, attitudes and practices related to sexual and reproductive health care for adolescents? A case study from Latin America. Trop Med Int Health. 2006c;11(6):889-898. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01632.x

- Azmat SK, Ali M, Hameed W, Awan MA. Assessing family planning service quality and user experiences in social franchising programme – Case studies from two rural districts in Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2018;30(2):187-197. http://jamc.ayubmed.edu.pk/index.php/jamc/article/download/3542/1894. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data—or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38(1):115-132. http://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2001.0003

- Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS Wealth Index. DHS Comparative Reports No. 6. Calverton, Maryland: ORC Macro; 2004. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/cr6/cr6.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Chakraborty NM, Fry K, Behl R, Longfield K. Simplified asset indices to measure wealth and equity in health Programs: A reliability and validity analysis using survey data from 16 countries. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4(1):141-154. http://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00384

- Gwatkin DR. The current state of knowledge about targeting health programs to reach the poor. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2000. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/29585. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Hanson K, Worrall E, Wiseman V. Targeting services towards the poor: A review of targeting mechanisms and their effectiveness. In: Mills A, Bennett S, Gilson L. Health, Economic Development and Household Poverty: From Understanding to Action. London: Routledge; 2007. 304 pp. https://www.eldis.org/document/A22157. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- McConnell M, Rothschild CW, Ettenger A, Muigai F, Cohen J. Free contraception and behavioural nudges in the postpartum period: Evidence from a randomised control trial in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2018;3(5):e000888. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000888

- Broughton EI, Hameed W, Gul X, Sarfraz S, Baig IY, Villanueva M. Cost-effectiveness of a family planning voucher program in rural Pakistan. Front Public Health. 2017;5:227. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00227

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). Family planning vouchers: a tool to boost contraceptive method access and choice. Washington, DC: HIPs partnership; 2020 June. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/family-planning-vouchers

Acknowledgements

This brief was updated by: Caroline Quijada and Marguerite Farrell with input from Ben Bellows, Luke Boddam-Whetham and Elaine Menotti. It was updated from previous drafts authored by Ben Bellows, Anna Mackay, Elaine Menotti, and Shawn Malarcher. Critical review and helpful comments were provided Michal Avni, Margaret D’Adamo, Molly Fitzgerald, Anna Gorter, Karen Hardee, Brendan Michael Hayes, Jeanna Holtz, Roy Jacobstein, Beverly Johnston, Jesse Joseph, Baker Maggwa, Erastus Maina, Emily Mangone, Ados May, Alice Payne Merritt, Erin Mielke, Ali Moazzam, Gael O’Sullivan, May Post, John Stanback, Sara Stratton, Nandita Thatte, Caitlin Thistle, and Matthew Wilson.

The following organizations contributed to the development of this brief: Abt Associates, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, CARE, Chemonics International, EngenderHealth, FHI360, FP2020, International Planned Parenthood Federation, IntraHealth International, Jhpiego, John Snow, Inc., Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, Management Sciences for Health, Palladium, PATH, Pathfinder International, Population Council, Population Reference Bureau, Population Services International, Promundo US, Public Health Institute, Save the Children, United Nations Population Fund, U.S. Agency for International Development, and the University Research Co., LLC.

The World Health Organization/Department of Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: http://www.who.int/topics/family_planning/en/.

For more information about HIPs, please contact the HIP team.

The HIPs represent a diverse and results-oriented partnership encompassing a wide range of stakeholders and experts. As such, the information in HIP materials does not necessarily reflect the views of each co-sponsor or partner organization.

Provide Comments

To provide comments on this brief, please fill out the form on the Community Feedback page.