Adolescent-Responsive Contraceptive Services: Institutionalizing adolescent-responsive elements to expand access and choice

Background

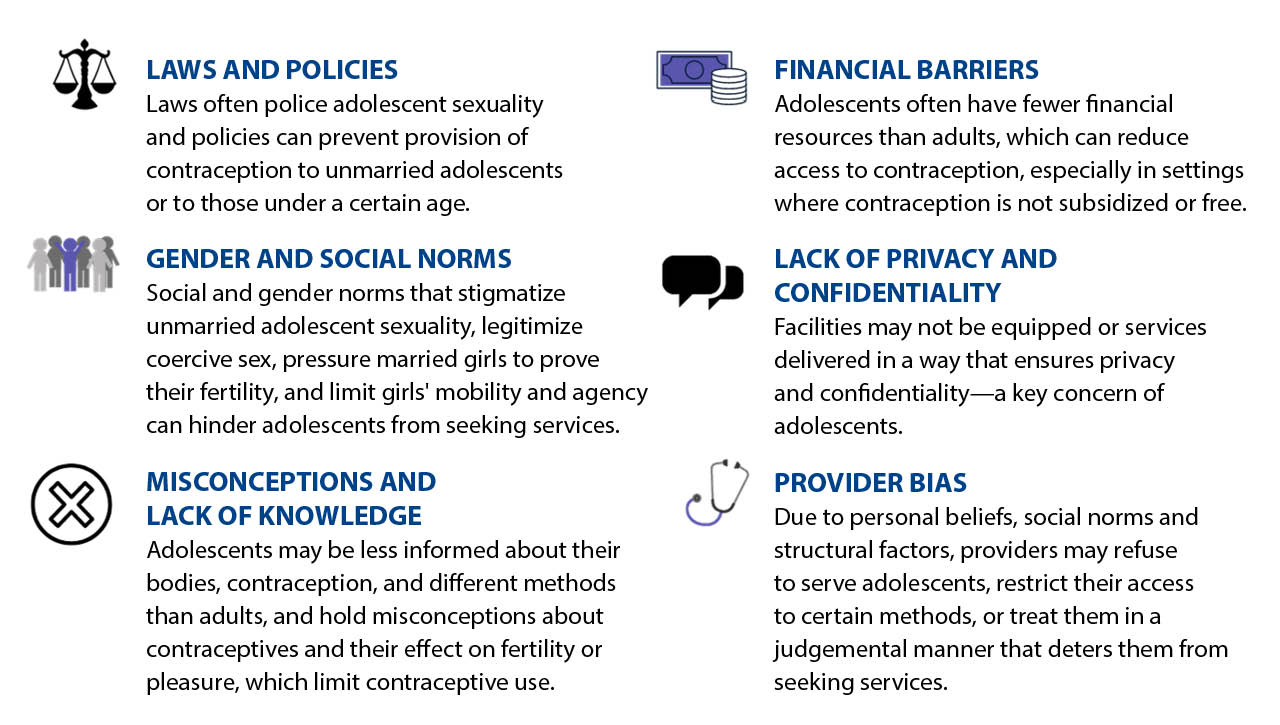

Adolescence, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ages 10 to 19, is a time of tremendous physical, cognitive, and social change1 and when many people initiate sexual activity.2 Adolescents need a range of supports to remain well, to transition safely into adulthood, and to adopt lifelong healthy behaviors; a key support is access to contraceptive information and services.3,4 However, many countries continue to invest in interventions that are ineffective at increasing contraceptive use (e.g., youth centers), demonstrate mixed effects (e.g., peer education), or are challenging to sustain and bring to scale (e.g., separate spaces for young people within health facilities).5-9 This contributes to poor sexual and reproductive health outcomes. For example, about half of all pregnancies among adolescent females (15 – 19 years) in developing regions being unintended.10 With 1.25 billion adolescents, increasing to 1.35 billion in 2050,11 and countries striving to achieve universal health coverage,1,12 health systems must go beyond piecemeal approaches to institutionalize service delivery that acknowledges adolescents as distinct from other age groups and addresses the barriers that limit adolescents’ access to and use of contraception (Figure 1).13-24

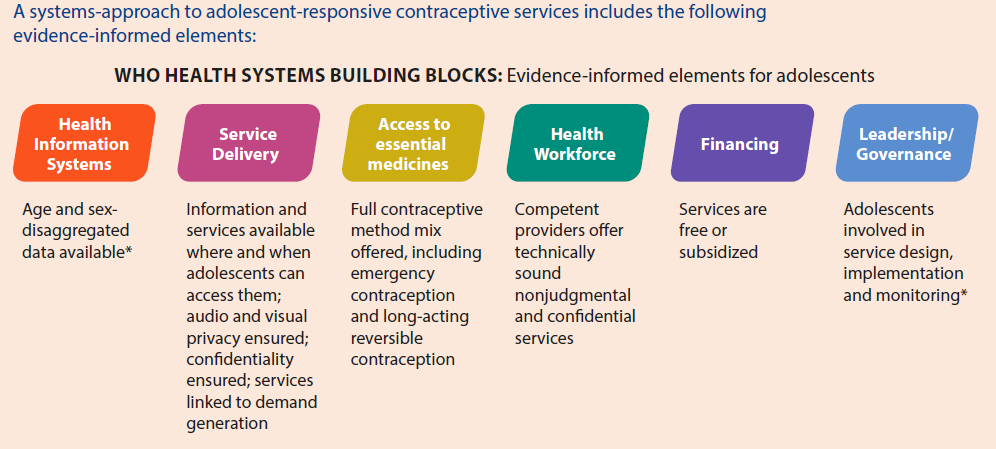

There is evidence that adolescent-friendly services, when well-designed and well-implemented, can help increase access to and use of contraception.25 However, traditional models of specialized service delivery for adolescents have proven difficult to sustain and scale (Box 1). Establishing adolescent-responsive contraceptive services (ARCS) is emerging as a more scalable and sustainable way to meet adolescents’ needs for contraceptive information and services. The term adolescent-responsive contraceptive services (ARCS) signals an evolution from traditional stand-alone models of adolescent-friendly services towards a systems approach to making existing contraceptive services adolescent-responsive by incorporating elements with demonstrated effectiveness for increasing adolescent contraceptive use (Box 2).4, 7, 12, 25-30 A systems approach implies that policies, procedures, and programs across the entire health system are adapted to respond to the diverse needs and preferences of adolescents.

ARCS is an “enhancement to high-impact practices in family planning” as identified by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. An enhancement is a practice that can be implemented in conjunction with HIPs to further intensify their impact. For more information about HIPs, see https://fphighimpactpractices.org/. For examples of how HIPs can be enhanced through the inclusion of adolescent-responsive elements, please see the ARCS Appendix document. This brief focuses on service delivery aspects of ARCS and does not discuss other investments that support adolescents’ use of contraception or that reduce adolescent births, such as girls’ education, community engagement, engaging men and boys, or social marketing, which are addressed in other HIP briefs.31-35

In an attempt to respond to adolescents’ concerns around stigma, privacy, and confidentiality, many programs and/or countries have implemented adolescent-friendly services using separate space models (e.g., offering adolescent-friendly services in a separate room within an existing health facility).8 However, separate space models have proven difficult to sustain and scale due to staff and resource shortages and low utilization of available specialized services, among many other constraints.9

that they are grounded in good public health practice and are important for adolescent-responsive service delivery 4, 12, 30.

What is the impact?

Evidence is accruing that investing in ARCS can improve adolescent contraceptive use,36-39 and Ethiopia and Chile are showing promising results. Specific actions taken by the government of Ethiopia included:

- The development of policies that supported adolescent access to contraceptive information

and services, regardless of age, parity, or marital status;40 - Changing health management information systems (HMIS) to collect age- disaggregated data for key indicators;

- Training and supervising health service providers;

- Using a variety of service delivery models and/or providers (health extension workers) to reach adolescents;

- Offering free contraceptive services;

- Providing a broad range of methods; refurbishing health facilities; and

- Institutionalizing administrative decision-making at the local level and linking service provision with community engagement and women’s empowerment activities.41-46

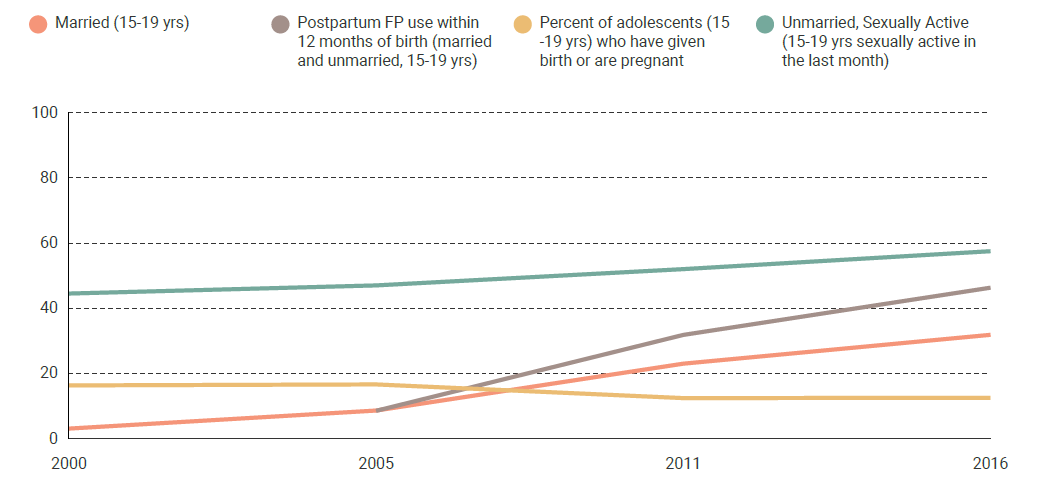

An adaptive management style and involvement of key stakeholders, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and professional associations, facilitated the adoption of these actions and policies.41 While it is not possible to attribute the relative contribution of these actions to increases in adolescent contraceptive use, Ethiopia has reported consistent or increasing contraceptive uptake among all sexually active adolescents and fewer adolescent births (Figure 2).47-49

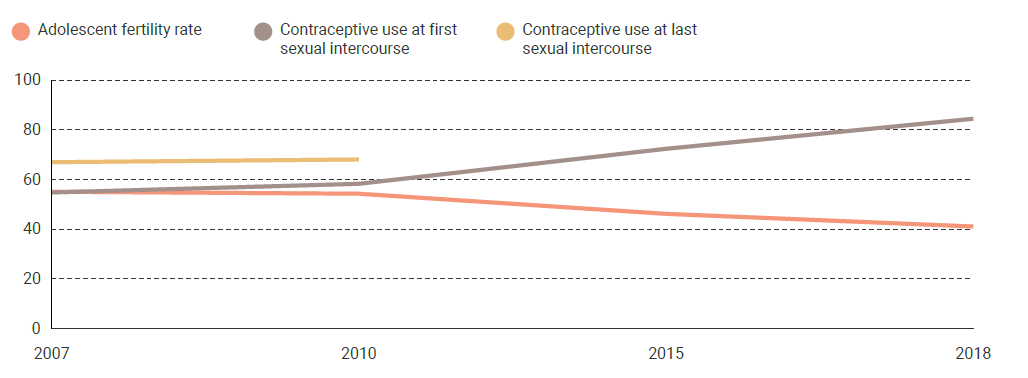

The Chilean government’s 10-year strategy (2011 – 2020) implemented a five-pronged systems-approach that trained health service providers; created adolescent-friendly spacesii in primary health centers; offered the full method mix; improved outreach and referrals; and created a legal framework that articulated stakeholder responsibilities. A monthly register gathered adolescent-specific data. Human and financial resources were sustained throughout the 10-year period, and coordination mechanisms were maintained.41 Advocacy and publicity highlighted the strategy’s positive outcomes, which helped to alleviate public resistance to providing contraception to adolescents. Positive outcomes included a decrease in the birth rate among adolescents aged 15-19:

- From 55.1 births per 1,000 women in 2007 to 41.1 births per 1,000 women in 2018);

- A 51% reduction in the proportion of births to mothers under the age of 19 between 2000-2017; and

- A 30% increase in reported contraceptive use at first sexual intercourse between 2007 and 2018 (Figure 3).41, 50-53

Other sectors implemented complementary efforts, showcasing the value of including ARCS within multi-sectoral adolescent programming.

ii The term adolescent-friendly is used here, as this was the official term used by Chile’s Ministry of Health when referring to these spaces (“espacios amigables para la salud de adolescentes”).

Note: The estimates for contraceptive use at first and last sexual intercourse are for all adolescents and not disaggregated by sex (sex-disaggregated data for this age group was not available in the National Youth Surveys for the respective years).

Although Ethiopia and Chile have not fully addressed the complete list of elements listed in Table 2, their results illustrate how a systems approach to providing ARCS can contribute to improving contraceptive uptake. When an adolescent-responsive lens is intentionally and systematically applied across the health system, the resulting system is stronger and is better able to sustain quality services at scale (Box 2).

The Governments of Chile, Ethiopia, and Uruguay have systematically invested in adolescent sexual and reproductive health. Each country developed its own approach to scale up adolescent-responsive sexual and reproductive health services, and the following points were commonalities in their efforts:37, 41

- Dedicated advocates created momentum for scale-up.

- Supportive policies enabled the development and implementation of evidence-informed

interventions. - The essential intervention package was simplified to the extent possible to facilitate scale-up.

- Communication around scale-up was clear and directive.

- Adequate resources were allocated.

- The scale up effort was effectively managed.

- Scale-up execution was systematic and pragmatic.

- Relevant stakeholders were actively engaged and contributed to sustainability.

- Assessments and periodic reviews enabled the adaptive management of programs and

effectively communicated successes. - Ongoing advocacy ensured sustained integration across policies, programs, strategies, services, and indicators.

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

This is a non-exhaustive list of tips for implementing ARCS. The tips are associated with WHO’s Health Systems Building Blocks to illustrate how to apply a systems approach to ARCS.54 A systems-approach will involve the implementation of these actions and will analyze and coordinate the relationships between them. Because this brief addresses contraceptive service delivery for adolescents, most tips are supply-side related. Demand-side tips can be found in other HIP briefs.31, 33-35

Ensure an enabling policy and legal environment for contraceptive provision to adolescents.

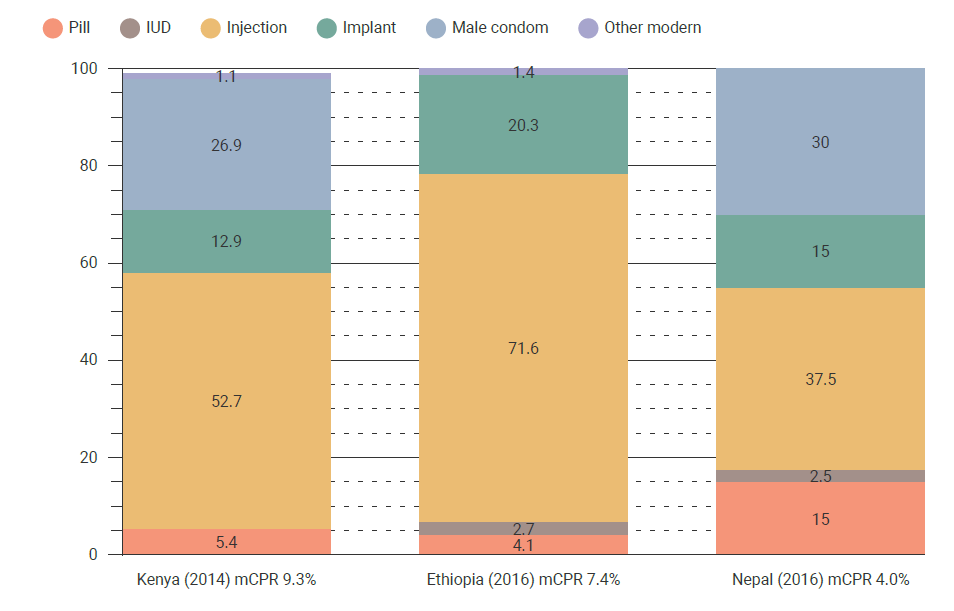

- Support the development, revision, and implementation of laws, policies, and service delivery guidelines that clearly state that all adolescents can obtain accurate, comprehensive sexual and reproductive health information, support in decision-making from a qualified health professional, respectful treatment, and voluntary choice of a full range of contraceptive methods regardless of age, marital status or parity.42, 55-60 Figure 4 shows method mix data from Kenya, Ethiopia, and Nepal highlighting that adolescents will use a variety of methods, including long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs), when offered a full range of contraceptive methods.49, 61, 62

- Ensure copies of relevant laws, policies, guidelines, and adolescent-friendly,iii service standards where they exist are widely available. Provider trainings and follow up support at facility level should reflect these legal rights, policies, guidelines, and standards.63, 64

iii The term adolescent-friendly is used here, as most countries continue to use this term when referring to national services standards.

Employ a variety of sectors and channels to reach different adolescent segments.

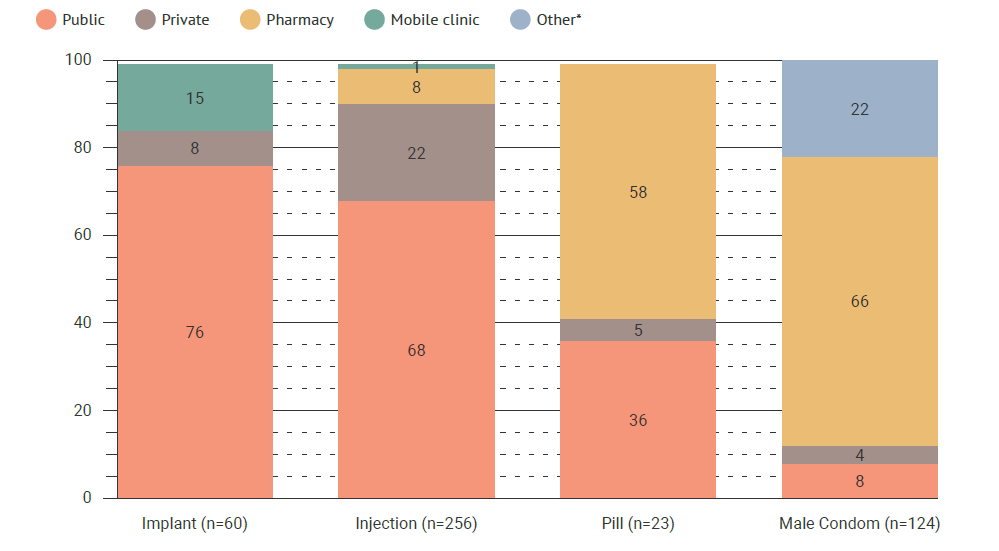

- Use different channels to reach a wide range of adolescents, taking into consideration adolescents’ needs and preferences, as well as the types of methods that can be provided through each channel. These include public and private-sector facilities, community-based distribution, mobile outreach services, pharmacies and drug shops, and school- or workplace-based services. Figure 5 shows an example from Kenya on the importance of offering adolescents a range of channels to obtain contraception.61

- Integrate contraceptive products and services into other health services, especially services that adolescents readily seek (e.g., HIV and MNCH) —this can be especially important from an equity perspective to reach certain adolescent segments (e.g., first-time parents, adolescent boys, etc.).

- Consider promising new modalities, especially relevant in the context of COVID-19, such as self-care models (e.g., self-injection of DMPA-SC),65,66 and direct-to-consumer models (e.g., digital platforms to provide counseling and home delivery of methods).67,68 Also, provide over-the-counter access to emergency contraception and oral contraceptive pills.

Link ARCS with social and behavior change interventions that address adolescent-specific cognitive, cultural, and social challenges and barriers.

- Link multi-sectoral demand-side and gender-transformative community engagement efforts to ARCS, including through strong referral networks.7, 31, 33, 34, 69-77

Total sample size of all users ages 15-19 is 463, and n=the number of users for the method.

Improve providers’ competency in providing ARCS.

- Use whole clinic training that equips all providers and staff, including support staff, with the competencies necessary to offer respectful care, including contraceptive information, counseling, and products to adolescents.78 This can build shared commitment to serving adolescents and complementary responsibilities for delivering ARCS.

- Train small groups using low dose, high frequency training methodologies79 that incorporate WHO’s Core Competencies in Adolescent Health and Development for Primary Care Providers.80

- Reinforce training through job descriptions that reference quality standards, job aids, refresher training, mentorship, and supportive supervision,7, 81 as training alone is insufficient in changing provider behavior.7, 82, 83 Complement trainings with interventions that address the individual situational, and social factors contributing to provider bias.23, 84 This can include values clarifications exercises and creating a supportive environment for change without placing blame on providers, in addition to the dissemination of guidelines and mentoring mentioned earlier.84

Collect and use data to design, improve, and track ARCS implementation.

- Use quantitative and qualitative data to determine the specific needs and preferences of different adolescent groups; identify who is not being reached with contraceptive services; and use a strategic approach to draw on evidence-based interventions that ensure adolescents clients are offered appropriate contraceptive services (See Adolescents: Improving Sexual and Reproductive Health of Young People: A Strategic Planning Guide).34

- Review existing health information systems to collect, compile, and analyze age- and sex-disaggregated data.39, 85, 86

- Collect adolescent feedback. This can be done through exit interviews, self-administered

questionnaires, digital platforms, mystery clients, or other approaches. - Include adolescent-focused indicators in quality improvement frameworks.

- Review data at the facility, district, and national level to ensure that corrective action is taken, and resources are appropriately allocated.29

Address financial barriers to adolescent contraceptive use.

- Include ARCS in universal health coverage (UHC) and national insurance schemes and/or use other approaches such as offering vouchers or offering subsidized services through social marketing, social franchising, and cost-recovery schemes.4, 7, 87

- Finance ARCS through national and sub-national budget allocations and distributions.

Support meaningful participation and leadership of adolescents.

- Ensure that national policies are designed and implemented to acknowledge adolescents’ rights to meaningful engagement and establish mechanisms that facilitate adolescents’

meaningful participation in the design, implementation, and monitoring of ARCS.29 - Support adolescents to effectively contribute to advocacy, governance, and accountability efforts.29, 88

Measurement and Indicators

The following indicators can be used to measure and monitor countries’ progress towards offering ARCS.89 Indicators 1a and 1b should be measured and analyzed together to give a more complete picture of contraceptive service delivery to adolescents.

1a. Number and percent of health facilities that currently provide adolescent contraceptive services (measured by the percent of facilities that provided contraceptive services to at least one adolescent in the last 3 months).iv

1b. Total number of contraceptive visits by clients under the age of 20 years.v

2. Proportion of districts (or other geographic area) in which adolescents aged 15-19 years have a designated place in community accountability mechanismsvi on access to and quality of health services. (The denominator is the number of districts with a community accountability mechanism in place, and the numerator is the number of them in which adolescents have a designated place.) 89 vii

iv Performance Indicator Reference Sheet forthcoming.

v For countries collecting family planning data for 10 – 14 yrs. and 15 – 19 yrs., this indicator should be calculated by taking the sum of both age bands. For countries that only collect FP data for 15 – 19 years, this indicator should be calculated by taking the sum of visits to 15 – 19 years.

vi Illustrative examples of community accountability mechanisms include: community audits, community score cards, monitoring citizen charters, public hearings, health committees at the district/ sub-district/ health facility levels, financial monitoring committees, public expenditure tracking surveys, school health management committees, and participatory research and evaluation.

vii This indicator is adapted from a forthcoming handbook on universal health coverage being developed by WHO and draws from evidence on social accountability, including Hurd et al. (2020).

- What are the factors and system conditions that allow for adolescent-responsive contraceptive services to be scaled and sustained?

- What actions have governments taken to integrate ARCS into UHC, and what were the results?

- What social accountability mechanisms—including those that are led by adolescents—could increase contraceptive services’ responsiveness for adolescents?

Search Strategy

To compile the list of documents meeting inclusion criteria, a literature search was conducted using bibliographic databases and hand searching of online websites for peer-reviewed articles and grey literature that highlight adolescents and family planning usage from 2015 to 2019.

For more information, download the Methods for literature search, information sources, abstraction and synthesis document.

References

- World Health Organisation, Health for the world’s adolescents. A second chance for a second decade. 2014, World Health Organisation: Geneva. Available from: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/second-decade/en/ Accessed on: April 2, 2020.

- Liang, M., et al., The State of Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2019. 65(6): p. S3-S15 DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.015.

- Patton, G.C., et al., Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. The Lancet, 2016. 387(10036): p. 2423-2478 DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1.

- World Health Organization, Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation 2017, World Health Organization: Geneva.

- Chandra-Mouli, V., C. Lane, and S. Wong, What Does Not Work in Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health: A Review of Evidence on Interventions Commonly Accepted as Best Practices. Global health, science and practice, 2015. 3(3): p. 333-340 DOI: 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00126.

- Zuurmond, M.A., R.S. Geary, and D.A. Ross, The effectiveness of youth centers in increasing use of sexual and reproductive health services: a systematic review. Stud Fam Plann, 2012. 43(4): p. 239-54 DOI: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00324.x.

- Denno, D.M., A.J. Hoopes, and V. Chandra-Mouli, Effective strategies to provide adolescent sexual and reproductive health services and to increase demand and community support. J Adolesc Health, 2015. 56(1 Suppl): p. S22-41 DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.012.

- Simon, C., et al., Thinking outside the separate space: A decision-making tool for designing youth-friendly services. 2015, Evidence to Action Project/Pathfinder International: Washington D.C. Available from: https://www.e2aproject.org/wp-content/uploads/thinking-outside-the-separate-space-yfs-tool.pdf

- Hainsworth, G., et al., Scale-up of Adolescent Contraceptive Services: Lessons From a 5-Country Comparative Analysis. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 2014. 66 Suppl 2: p. S200-8 DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000180.

- Darroch, J.E., et al., Adding It Up: Costs and Benefits of Meeting the Contraceptive Needs of Adolescents. 2016, Guttmacher Institute: New York. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/adding-it-meeting-contraceptive-needs-of-adolescents

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Probabilistic Population Projections Rev. 1 based on the World Population Prospects 2019 Rev. 1. 2019. Available from: http://population.un.org/wpp/

- Lehtimaki, S., N. Schwalbe, and L. Sollis, Adolescent Health: The Missing Population in Universal Health Coverage. 2019, Plan International: Woking. Available from: https://plan-uk.org/sites/default/files/Adolescent%20Health%20%20UHC%20Report_FINAL%20May%202019.pdf

- Atuyambe, L., et al., Understanding sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents: Evidence from a formative evaluation in Wakiso district, Uganda Adolescent Health. Reproductive health, 2015. 12: p. 35 DOI: 10.1186/s12978-015-0026-7.

- Amankwaa, G., K. Abass, and R. Gyasi, In-school adolescents’ knowledge, access to and use of sexual and reproductive health services in Metropolitan Kumasi, Ghana. Journal of Public Health, 2018. 26 DOI: 10.1007/s10389-017-0883-3.

- Ayehu, A., T. Kassaw, and G. Hailu, Level of Young People Sexual and Reproductive Health Service Utilization and Its Associated Factors among Young People in Awabel District, Northwest Ethiopia. PLOS ONE, 2016. 11(3): p. e0151613 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151613.

- Banerjee, S.K., et al., How prepared are young, rural women in India to address their sexual and reproductive health needs? a cross-sectional assessment of youth in Jharkhand. Reproductive health, 2015. 12: p. 97-97 DOI: 10.1186/s12978-015-0086-8.

- Barroy, H., et al., Addressing Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Niger, in Health, Nutrition and Population Discussion Paper. 2016, World Bank: Washington D.C. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/24432

- Birhanu, Z., K. Tushune, and M.G. Jebena, Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Use, Perceptions, and Barriers among Young People in Southwest Oromia, Ethiopia. Ethiopian journal of health sciences, 2018. 28(1): p. 37-48 DOI: 10.4314/ejhs.v28i1.6.

- Capurchande, R., et al., “It is challenging… oh, nobody likes it!”: a qualitative study exploring Mozambican adolescents and young adults’ experiences with contraception. BMC women’s health, 2016. 16: p. 48-48 DOI: 10.1186/s12905-016-0326-2.

- de Castro, F., et al., Perceptions of adolescent ‘simulated clients’ on barriers to seeking contraceptive services in health centers and pharmacies in Mexico. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 2018. 16: p. 118-123 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2018.03.003.

- Donahue, C., et al., Adolescent access to and utilisation of health services in two regions of Côte d’Ivoire: A qualitative study. Glob Public Health, 2019. 14(9): p. 1302-1315 DOI: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1584229.

- Geary, R.S., et al., Evaluating youth-friendly health services: young people’s perspectives from a simulated client study in urban South Africa. Glob Health Action, 2015. 8: p. 26080 DOI: 10.3402/gha.v8.26080.

- Starling, S., et al., Literature Review and Expert Interviews on Provider Bias in the Provision of Youth Contraceptive Services: Research Summary and Synthesis. 2017, Pathfinder International: Washington D.C. Available from: https://www.pathfinder.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/BB_Research-Synthesis.pdf

- Müller, A., et al., “You have to make a judgment call”. – Morals, judgments and the provision of quality sexual and reproductive health services for adolescents in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 2016. 148: p. 71-78 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.048.

- Brittain, A.W., et al., Youth-Friendly Family Planning Services for Young People: A Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med, 2015. 49(2 Suppl 1): p. S73-84 DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.019.

- Senderowitz, J., Making Reproductive Health Services Youth Friendly. 1999, Pathfinder International: Washington D.C. Available from: https://www.pathfinder.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Making-Reproductive-Health-Services-Youth-Friendly.pdf

- Bankole, A. and S. Malarcher, Removing Barriers to Adolescents’ Access to Contraceptive Information and Services. Studies in family planning, 2010. 41: p. 117-24 DOI: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00232.x.

- Erulkar, A.S., C.J. Onoka, and A. Phiri, What is youth-friendly? Adolescents’ preferences for reproductive health services in Kenya and Zimbabwe. Afr J Reprod Health, 2005. 9(3): p. 51-8.

- World Health Organization, Global standards for quality health-care services for adolescents. A guide to implement a standards-driven approach to improve the quality of health care services for adolescents. 2015, WHO: Geneva. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/183935/9789241549332_vol1_eng.pdf;jsessionid=C2434185AB56F765BE6BE25FE2F3D4A3?sequence=1

- Catino, J., E. Battistini, and A. Babcheck, Young People Advancing Sexual and Reproductive Health: Toward a New Normal. 2019, YIELD Project: Seattle. Available from: https://www.summitfdn.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/YIELD_full-report_June-2019.pdf

- High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs), Educating girls: creating a foundation for positive sexual and reproductive health behaviors. 2014, USAID: Washington D.C. Available from: http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/educating-girls

- High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs), Community engagement: changing norms to improve sexual and reproductive health. 2016, USAID: Washington D.C. Available from: http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/community-group-engagement.

- High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs), Engaging Men and Boys in Family Planning: A Strategic Planning Guide. 2018, USAID: Washington D.C. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/guides/engaging-men-and-boys-in-family-planning/

- High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs), Adolescents: Improving Sexual and Reproductive Health of Young People: A Strategic Planning Guide. 2015, USAID: Washington D.C. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/guides/improving-sexual-and-reproductive-health-of-young-people/

- High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs), Social marketing: leveraging the private sector to improve contraceptive access, choice, and use. 2013, USAID: Washington D.C. Available from: http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/social-marketing

- Chandra-Mouli, V., S. Chatterjee, and K. Bose, Do efforts to standardize, assess and improve the quality of health service provision to adolescents by government-run health services in low and middle income countries, lead to improvements in service-quality and service-utilization by adolescents? Reprod Health, 2016. 13: p. 10 DOI: 10.1186/s12978-015-0111-y.

- Chandra-Mouli, V., et al., The Political, Research, Programmatic, and Social Responses to Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in the 25 Years Since the International Conference on Population and Development. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2019. 65(6, Supplement): p. S16-S40 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.011.

- Chandra-Mouli, V., et al., Programa Geração Biz, Mozambique: how did this adolescent health initiative grow from a pilot to a national programme, and what did it achieve? Reproductive health, 2015. 12: p. 12-12 DOI: 10.1186/1742-4755-12-12.

- Huaynoca, S., et al., Documenting good practices: scaling up the youth friendly health service model in Colombia. Reproductive Health, 2015. 12(1): p. 90 DOI: 10.1186/s12978-015-0079-7.

- Harris, S., et al., Youth Family Planning Policy Scorecard: Measuring Commitment to Effective Policy and Program Interventions. 2020, Population Reference Bureau: Washington D.C. Available from: https://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Youth-Family-Planning-Scorecard-2020_English.pdf

- Chandra-Mouli, V., et al., Lessons learned from national government led efforts to reduce adolescent pregnancy in Chile, England and Ethiopia. 2019.

- Fikree, F.F., et al., Strengthening Youth Friendly Health Services through Expanding Method Choice to include Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives for Ethiopian Youth. Afr J Reprod Health, 2017. 21(3): p. 37-48 DOI: 10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i3.3.

- Pathfinder International, Bringing Youth-Friendly Services to Scale in Ethiopia. 2012, Pathfinder International: Watertown. Available from: http://www2.pathfinder.org/site/DocServer/Bringing_Youth-Friendly_Services_to_Scale_in_Ethiopia.pdf?do-

- Pathfinder International, Youth-friendly Services: Piloting to Scaling-up in Ethiopia. 2016. Available from: https://www.pathfinder.org/publications/youth-friendly-services-piloting-scaling-ethiopia/

- Hounton, S., et al., Patterns and trends of contraceptive use among sexually active adolescents in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, and Nigeria: Evidence from cross-sectional studies. Global Health Action, 2015. Glob Health Action 2015, 8: 29737 DOI: 10.3402/gha.v8.29737.

- Damtew, Z.A., C.T. Chekagn, and A.S. Moges, The health extension program of Ethiopia: Strengthening the community health system. Harvard Health Policy Review, 2016.

- Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. 2012, Central Statistical Agency and ICF International: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA.

- Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. 2006, Central Statistical Agency and ORC Macro: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA.

- Central Statistical Agency/CSA/Ethiopia and ICF international, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. 2016, CSA and ICF International: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- INJUV, Quinta Encuesta Nacional de Juventud. 2007, Instituto Nacional de la Juventud: Santiago, Chile.

- INJUV, Sexta. Encuesta Nacional de Juventud. 2010, Instituto Nacional de la Juventud: Santiago, Chile.

- INJUV, Novena Encuesta Nacional de Juventud. 2019, Instituto Nacional de la Juventud: Santiago, Chile.

- Salud Sexual Salud Reproductiva y Derechos Humanos en Chile. Estado de Situación 2016, C. Dides and C. Fernández, Editors. 2016, Corporaci Miles: Santiago, Chile.

- World Health Organization, Everybody business : strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes : WHO’s framework for action. 2007, World Health Organization: Geneva. Available from: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf Accessed on: 27 May, 2020.

- Arinze‑Onyia, S., E. Aguwa, and E. Nwobodo, Health education alone and health education plus advance provision of emergency contraceptive pills on knowledge and attitudes among university female students in Enugu, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 2014. 17(1) DOI: 10.4103/1119-3077.122858.

- World Health Organization, Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. Fifth edition. 2015, World Health Organization: Geneva. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/MEC-5/en/

- Thapa, S., A new wave in the quiet revolution in contraceptive use in Nepal: the rise of emergency contraception. Reproductive Health, 2016. 13(1): p. 49 DOI: 10.1186/s12978-016-0155-7.

- Global Statement: Committing ourselves to full and informed choice of contraceptives for adolescents and youth. Available from: http://www.familyplanning2020.org/youth-larc-statement Accessed on: 9 November, 2020.

- Fikree, F.F., et al., Making good on a call to expand method choice for young people – Turning rhetoric into reality for addressing Sustainable Development Goal Three. Reproductive Health, 2017. 14(1): p. 53 DOI: 10.1186/s12978-017-0313-6.

- Kaewkiattikun, K., Effects of immediate postpartum contraceptive counseling on long-acting reversible contraceptive use in adolescents. Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics, 2017. 8: p. 115-123 DOI: 10.2147/AHMT.S148434.

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, et al., Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014. 2015, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health/Kenya, National AIDS Control Council/Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute, National Council for Population and Development/Kenya, and ICF International: Rockville, MD, USA.

- Ministry of Health/Nepal, New ERA/Nepal, and ICF, Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016. 2017, Ministry of Health Nepal/Nepal, New ERA/Nepal, ICF: Kathmandu, Nepal.

- Greifinger, R. and M. Ramsey, Making Your Health Services Youth-Friendly: A GUIDE FOR PROGRAM PLANNERS AND IMPLEMENTERS. 2014, Population Services Internationa: Washington D.C.

- Senderowitz, J., C. Solter, and G. Hainsworth, Clinic Assessment of Youth Friendly Services: A Tool for Assessing and Improving Reproductive Health Services for Youth. 2002, Pathfinder International: Watertown, MA. . Available from: http://www2.pathfinder.org/site/DocServer/mergedYFStool.pdf?docID=521 Accessed on: 9 November, 2020.

- World Health Organization, WHO consolidated guideline on self-care interventions for health: sexual and reproductive health and rights: executive summary (No. WHO/RHR/19.14). 2019, World Health Organization: Geneva.

- Cover, J., et al., PRESENTATION: Adolescent client survey results (Adolescent Platform) from the Self-injection Best Practices program evaluation. 2019, PATH: Seattle.

- Green, E.P., et al., “What is the best method of family planning for me?”: a text mining analysis of messages between users and agents of a digital health service in Kenya. Gates open research, 2019. 3: p. 1475-1475 DOI: 10.12688/gatesopenres.12999.1.

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs), Digital health for Social and Behavior Change: New technologies, new ways to reach people. 2017, USAID: Washington D.C. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/digital-health-sbc/

- Firestone, R., et al., Intensive Group Learning and On-Site Services to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health Among Young Adults in Liberia: A Randomized Evaluation of HealthyActions. Global Health: Science and Practice, 2016. 4(3): p. 435-451 DOI: 10.9745/ghsp-d-16-00074.

- Futures Group International, End of Project Report: Jamaica Adolescent Reproductive Health Activity. 2005, Futures Group International: Washington D.C.

- Gottschalk, L.B. and N. Ortayli, Interventions to improve adolescents’ contraceptive behaviors in low- and middle-income countries: a review of the evidence base. Contraception, 2014. 90(3): p. 211-225 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.017.

- Kesterton, A.J. and M. Cabral de Mello, Generating demand and community support for sexual and reproductive health services for young people: A review of the Literature and Programs. Reproductive Health, 2010. 7(1): p. 25 DOI: 10.1186/1742-4755-7-25.

- Hardee, K., M. Croce-Galis, and J. Gay, Are men well served by family planning programs? Reproductive Health, 2017. 14(1): p. 14 DOI: 10.1186/s12978-017-0278-5.

- McCleary-Sills, J., et al., Womens demand for reproductive control: Understanding and addressing gender barriers. Journal of Biosocial Science, 2012. 44(1): p. 43-56.

- Jejeebhoy, S.J., et al., Meeting Contraceptive Needs: Long-Term Associations Of the PRACHAR Project with Married Women’s Awareness and Behavior in Bihar. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2015. 41(3): p. 115-125 DOI: 10.1363/4111515.

- Fleming, P.J., et al., Can a Gender Equity and Family Planning Intervention for Men Change Their Gender Ideology? Results from the CHARM Intervention in Rural India. Studies in Family Planning, 2018. 49(1): p. 41-56 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12047.

- Raj, A., et al., Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluation of a Gender Equity and Family Planning Intervention for Married Men and Couples in Rural India. PLOS ONE, 2016. 11(5): p. e0153190 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153190.

- Winston, J., et al., Impact of the Urban Reproductive Health Initiative on family planning uptake at facilities in Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal. BMC Women’s Health, 2018. 18(1): p. 9 DOI: 10.1186/s12905-017-0504-x.

- Jhpiego, Low Dose, High Frequency: A Learning Approach to Improve Health Workforce Competence, Confidence, and Performance 2016, Jhpiego: Baltimore. Available from: https://hms.jhpiego.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/LDHF_briefer.pdf Accessed on: 9 November, 2020.

- World Health Organization, Core competencies in adolescent health and development for primary care providers: Including a tool to assess the adolescent health and development component in pre-service education of health-care providers. 2015, World Health Organization: Geneva.

- Chandra-Mouli, V. and E. Akwara, Improving access to and use of contraception by adolescents: What progress has been made, what lessons have been learnt, and what are the implications for action? Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 2020. 66: p. 107-118 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.04.003.

- Barden-O’Fallon, J., et al., Evaluation of mainstreaming youth-friendly health in private clinics in Malawi. BMC Health Services Research, 2020. 20(1): p. 79 DOI: 10.1186/s12913-020-4937-9.

- Rowe, A.K., et al., How can we achieve and maintain high-quality performance of health workers in low-resource settings? The Lancet, 2005. 366(9490): p. 1026-1035 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67028-6.

- Solo, J. and M. Festin, Provider Bias in Family Planning Services: A Review of Its Meaning and Manifestations. Global Health: Science and Practice, 2019. 7(3): p. 371-385 DOI: 10.9745/ghsp-d-19-00130.

- Neal, S., et al., Mapping adolescent first births within three east African countries using data from Demographic and Health Surveys: exploring geospatial methods to inform policy. Reproductive Health, 2016. 13(1): p. 98 DOI: 10.1186/s12978-016-0205-1.

- Neal, S., et al., Trends in adolescent first births in five countries in Latin America and the Caribbean: disaggregated data from demographic and health surveys. Reproductive Health, 2018. 15(1): p. 146 DOI: 10.1186/s12978-018-0578-4.

- Burke, E., et al., Youth Voucher Program in Madagascar Increases Access to Voluntary Family Planning and STI Services for Young People. Global Health: Science and Practice, 2017. 5(1): p. 33-43 DOI: 10.9745/ghsp-d-16-00321.

- Engel, D.M.C., et al., A Package of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Interventions—What Does It Mean for Adolescents? Journal of Adolescent Health, 2019. 65(6, Supplement): p. S41-S50 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.014.

- Hurd, S., M. Folse, and S. Fox, In Brief: Evidence on the Role of Social Accountability in Advancing Women, Children, and Adolescents’ Health. Global Health Visions. 2020, Global Health Visions: Saugerties, NY. Available from: https://www.globalhealthvisions.com/docs/in-brief-evidence-on-the-role-of-social-accountability-in-advancing-women-children-and-adolescents-health

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Adolescent-Responsive Contraceptive Services: Institutionalizing adolescent-responsive elements to expand access and choice. Washington, DC: HIPs Partnership; 2021 March. Available from:

http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/adolescent-responsive-contraceptive-services

Acknowledgements

This HIP enhancement was authored by Venkatraman Chandra-Mouli (World Health Organization), Katie Chau (Independent Consultant), Jill Gay (What Works Association), Gwyn Hainsworth (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation), Lynn Heinisch (Independent Consultant), Catherine Lane (Family Planning 2020), and Aditi Mukherji (YP Foundation).

This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Elsie Akwara (WHO), Jason Bremner (FP2030), Satvika Chalasani (UNFPA), Peter Fajans (ExpandNet) Laura Ghiron (ExpandNet), Jennie Greaney (UNFPA), Meghan Greeley (Jhpiego), Jamie Greenberg (Institute of Reproductive Health), Maja Hansen (UNFPA), Anjalee Kohli (Institute of Reproductive Health), Ricky Lu (Jhpiego), Rebecka Lundgren (University of California San Diego), Katie Meyer (Save the Children), Erin Portillo (Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs), Shannon Pryor (Save the Children), Eric Ramirez-Ferrero (E2A/Pathfinder International), Laura Raney (FP2030), Elaine E. Rossi (JSI), Rachel Shapiro (CARE), Ruth Simmons (ExpandNet), Callie Simon (Save the Children), Shefa Sikder (CARE), Sara Stratton (Palladium), Renata Tallarico (UNFPA), Amy Uccello (USAID), and Melanie Yahner (Save the Children).

The World Health Organization/Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of these documents which are viewed as a summary of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs are used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: http://www.who.int/topics/family_planning/en/.

For more information about HIPs, please contact the HIP team https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/contact/

The HIP Partnership is a diverse and results-oriented partnership encompassing a wide range of stakeholders and experts. As such, the information in HIP materials does not necessarily reflect the views of each co-sponsor or partner organization.