Family Planning and Immunization Integration: Reaching postpartum women with family planning services

Background

Most women in the extended postpartum period want to delay or avoid future pregnancies but many are not using a modern contraceptive method.2 Improving uptake of postpartum family planning (PPFP) can enhance the health of women, infants, and children. Closely spaced births (less than 18 to 24 months apart) are associated with increased maternal, newborn, and child morbidity and mortality including preterm birth, low birth weight, and increased neonatal and under age 5 death.3–6 Evidence also suggests that unintended pregnancies are associated with negative outcomes such such as increased likelihood of inadequate immunization, stunting, and increased maternal anxiety and depression.7-8 Despite the significant benefits of the use of voluntary family planning to save lives and improve health outcomes, a large proportion of women in the extended postpartum period may not access contraception as suggested by the fact that birth-to-pregnancy intervals in 50% or more of pregnancies in many low- and middle-income countries are too short (less than 23 months).2 Given this, it is crucial to take advantage of every health care contact with pregnant and postpartum women to offer family planning information, counseling, and services.

This HIP Brief focuses on integration of family planning with immunization during the extended postpartum period, which is the one-year period after delivery. Additional opportunities beyond this can be identified in vaccination schedules for the second year of life and beyond.

Immunization services offer an important opportunity to reach underserved women in the extended postpartum period. Immunization is one of the most widely used health services globally as shown by high vaccination coverage, with approximately one billion children vaccinated over the past decade.9 There are multiple touch points through the repeated visits needed to follow the recommended vaccination schedule during the first year of an infant’s life. Integration offers benefits such as mitigating constraints related to transportation costs and time while also reducing the burden on the overall health system and, potentially, on individual workloads.

Offering family planning services to postpartum women through infant-child immunization contacts is one of several promising “high-impact practices” (HIPs) in family planning identified by the HIP partnership and vetted by the HIP Technical Advisory Group.

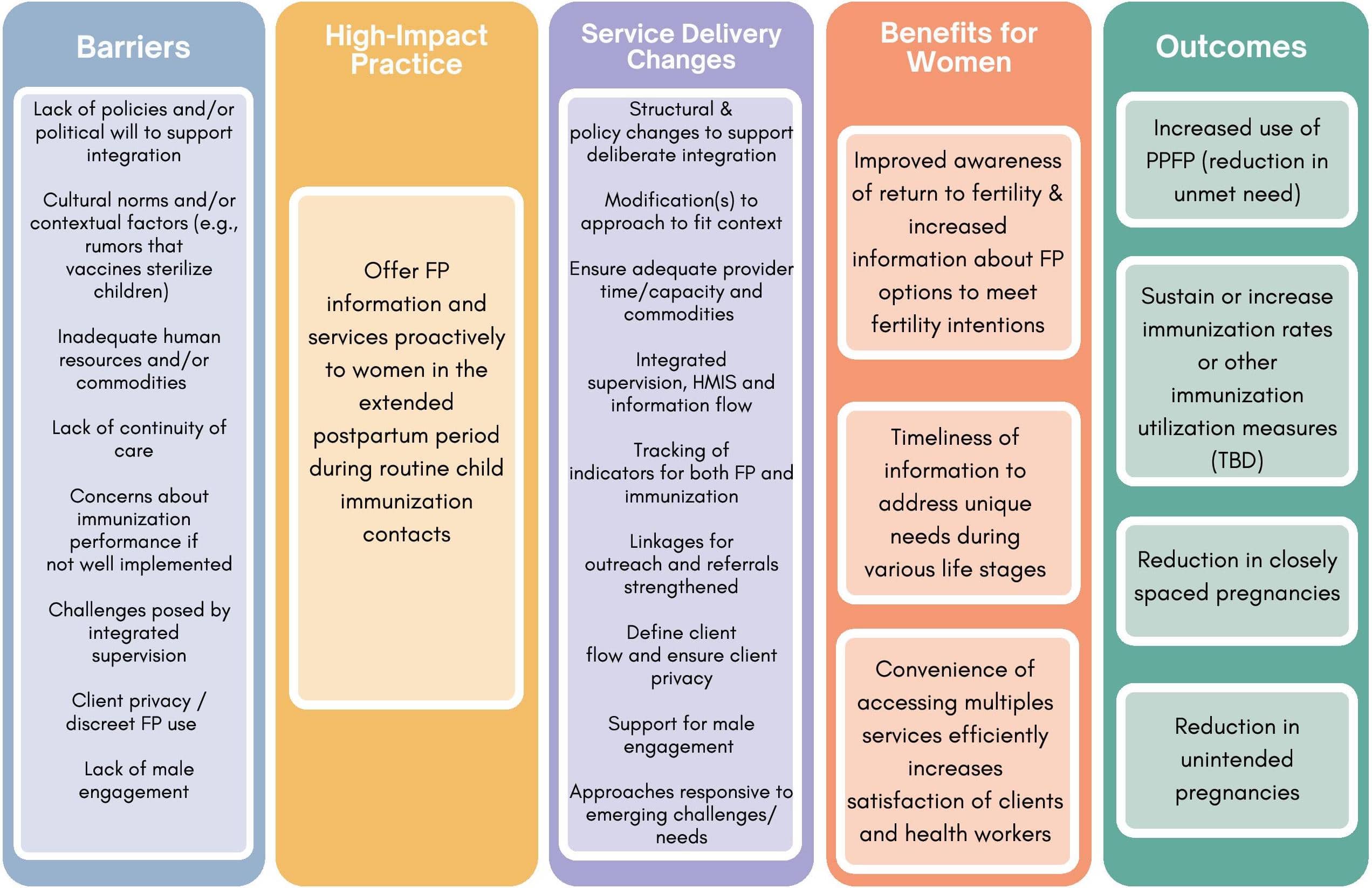

Central to this HIP is the recognition that integration requires deliberate efforts to put in place and/or tailor systems, resources, and practices to establish and support the integrated services. Deliberate efforts extend beyond training alone and must include a multi- pronged approach adapted to the local context. The Theory of Change (Figure 1) for this HIP highlights key barriers and service delivery challenges that must be addressed.

Why is this practice important?

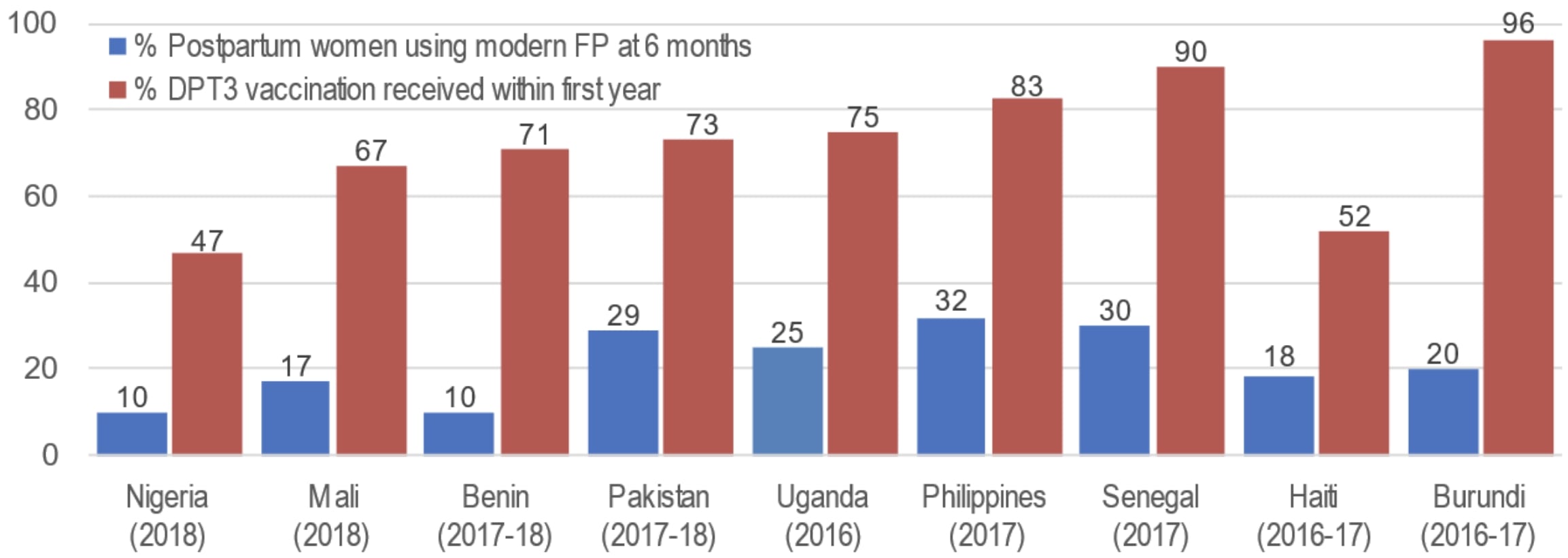

The broad reach and high use of immunization services reflects an ideal opportunity to reach large numbers of postpartum women with family planning. Immunization services are a cornerstone of the primary health care system, reaching more people than any other health service globally.10 Analysis across 68 countries showed that women are often more likely to access routine infant immunization services than family planning services.11 Figure 2 shows the percent of women 6 months postpartum currently using any modern contraceptive method compared to the percent of children who received their third dose protecting against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis-containing vaccine (DTP-3) by age one based on data from Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) in selected countries.

Figure 2 highlights that immunization services may offer an opportunity to reach many women who are taking their children to be immunized and who may also want to access family planning.

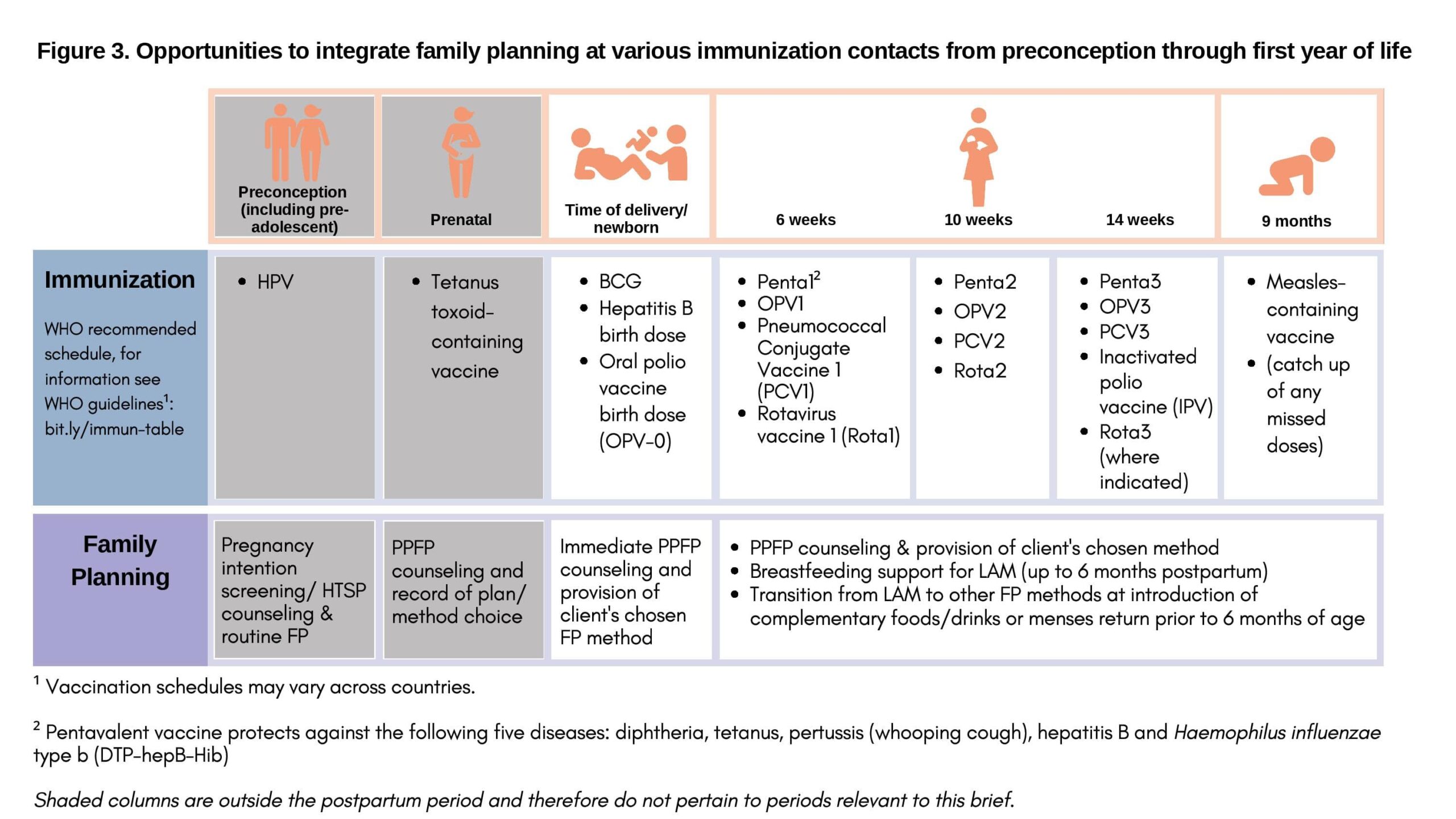

Child immunization services involve multiple timely contacts with mothers during the first year postpartum. The WHO recommended schedule for the first year of life includes vaccinations at birth, 6 weeks, 10 weeks, 14 weeks, and 9 months,12 providing opportunity through multiple contacts with the mother to offer family planning.13 Figure 3 highlights some opportunities to integrate family planning and immunization at various contacts.

Evidence suggests that an integrated model is largely acceptable to clients and service providers without having a negative impact on immunization uptake. Several studies have found providers and users accept family planning and immunization integration and found no negative impact on immunization uptake.14–17 A study in Malawi found substantial perceived benefits associated with family planning and immunization integration among providers and clients, including time-savings for both groups, and perceptions of improved health among women and young children. Most clients reported that an integrated approach allowed them to access the two services in one day at the same place, unlike in the past. Also, some health care workers noted that integration “improved referrals of clients between the two services.”15 A study in Liberia found high acceptability of family planning and immunization integration when offered in clinics and no negative impact on utilization of immunization services.18 In an assessment in Rwanda, 98% of women interviewed supported the idea of integrating family planning service components into infant immunization services.16 Additionally, a study conducted in two northwest Ethiopian districts and another study conducted with survey data from Ethiopia, Malawi, and Nigeria found an association between contraceptive use and child immunization.19,20 It should be noted that in one assessment in four African countries (Kenya, Mali, Ethiopia, and Cameroon), some providers expressed concern about integration potentially being time- and labor-intensive.17

What is the impact?

The existing evidence suggests that when well planned and executed, family planning and immunization integration services can lead to increased family planning uptake with no negative impact on immunization (Table 1). The service delivery models below (and in Figure 4) are summarized from the studies in Table 1.

Summary of intervention studies where family planning was systematically offered as part of immunization services

| Country/Citation | Intevention | Effect on Family Planning Uptake | Effect on Immunization Services |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt, Ahmed, et al., 201324 | FP counseling to first-time mothers bringing children to immunization services. In the control group no family planning counseling was provided. | The rate of use of family planning methods was higher in women in the intervention group than in the control group. | Not assessed |

| Liberia, Cooper et al., 201514 | Co-located provision of same-day, facility based services: vaccinators were trained to provide family planning messages using job aids and same-day family planning referrals to mothers bringing their infants to the facility for routine immunizations. | Increased new contraceptive users among women referred from immunization services to same day, co-located family planning clinic. | Increase in the number of Penta1 and Penta3 doses administered across pilot sites compared with the same period of the previous year in sites in Lofa. In sites in Bong little difference. |

| Malawi, Cooper et al., 202015 | Nurses and Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs) offered same day family planning services to mothers seeking routine infant immunization services at facilities. Nurses and HSAs screened family planning clients who were mothers of infants for immunization schedule completion or a need for infant immunization services. During outreach sessions, HSAs offered mothers routine infant immunization and family planning services, including direct provision of pills, condoms, and injectables and referrals for other methods. | Increase in family planning uptake and use at both facility and community service points with integration of family planning and immunization including same-day referrals at co-located facilities and inter-facility linkages. | No negative impact on immunization doses delivered or dropout rates. |

| Nepal, Phillipson, 201323 | For women bringing children to immunization services, group education about healthy timing of pregnancies followed by an immunization provider giving further family planning counseling to women who indicated they wish to use contraception. Internal referral provided for methods available at clinic (short acting) or external referral to methods not available on-site (long acting). | Increase in family planning uptake among hard-to-reach populations via integration with immunization service | No effect on routine utilization of immunization services |

| Rwanda, Dulli et al., 201616 | The intervention included family planning group education to women attending immunization services, a family planning brochure, individual family planning screening by an immunization provider or another provider while the child was being immunized, and referral to co-located family planning services. | Increase in uptake and modern contraceptive use | No negative impact on uptake or utilization |

| Togo, Huntington et al., 199422 | For women bringing children to immunization services, the provider encourages clients to go to same-day co-located family planning services | Family planning uptake increased in the intervention group. Awareness of family planning service availability also increased significantly among this group. | Significant increase in the number of vaccines administered per month during the study period in the intervention and control groups. |

| Did not achieve intended family planning outcome | |||

| Ghana & Zambia, Vance et al., 201421 | Vaccinators were trained to provide individualized family planning messages and same-day referrals to co-located family planning services to women presenting their child for immunization services. There were challenges with fidelity of intervention implementation in this study. | No significant difference in non-condom family planning use. No improvement in referrals to family planning services. Women’s knowledge of factors related to return of fecundity did not improve. | Not assessed |

| Liberia, Nelson et al., 201918 | Referral of women and their children from immunization services to family planning and vice versa for same-day services at the facility. Family planning leaflets provided to clients who were interested but needed more time to decide. Privacy screens not provided despite shown to be essential in pilot. | Slightly higher family planning uptake in intervention over non-intervention facilities, but differences were not statistically significant. | No negative impact on uptake or utilization of immunization services; no increase in dropout rates. |

NSSC: No statistically significant change

+ indicates statistically significant positive change at the .01 level or higher

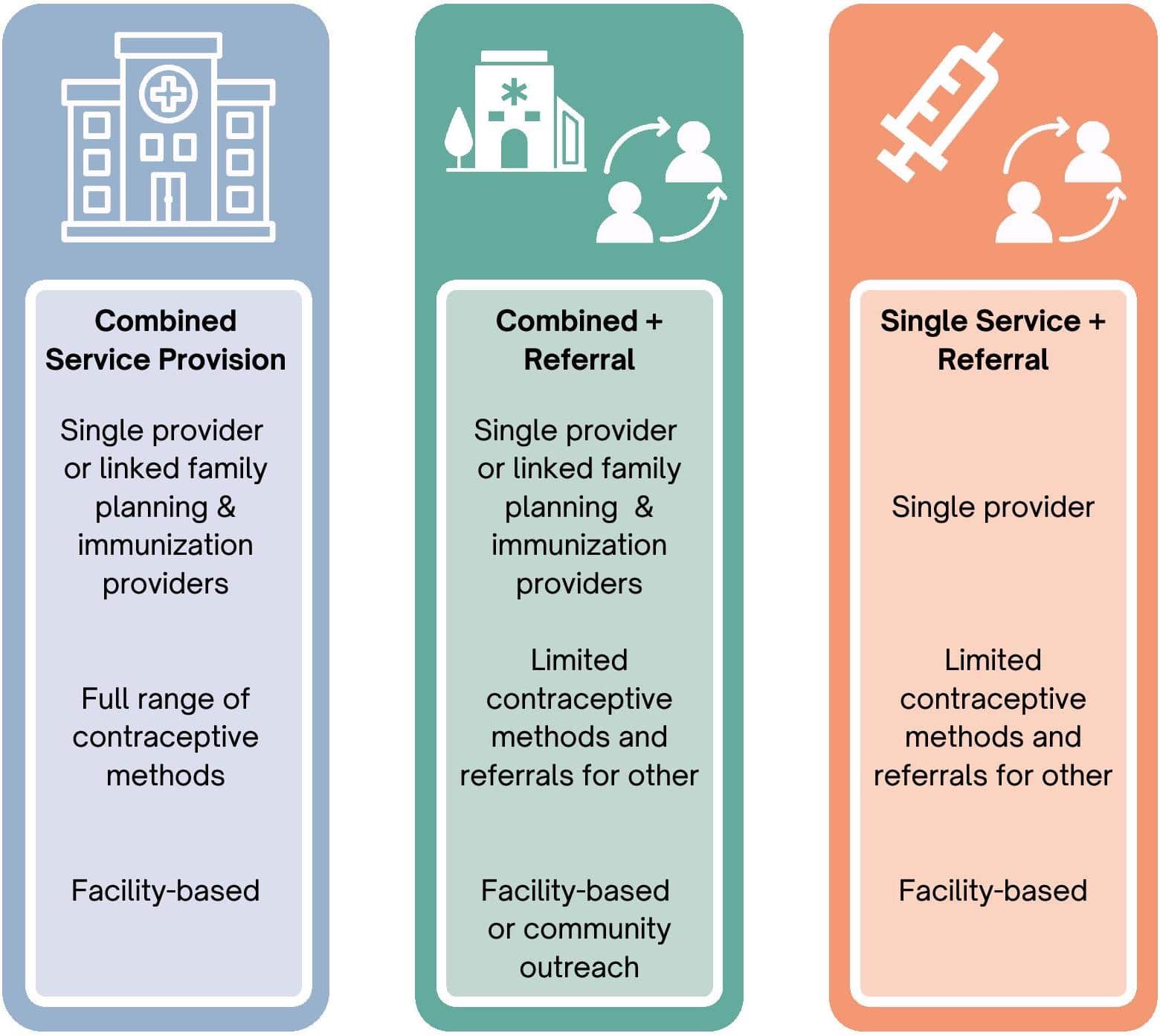

- Combined Service Provision: This model entails the availability of co-located, same-day family planning services during routine immunization visits. This approach may involve group talks, individualized screening, or brief motivational messages given with the immunization service that link the two services. Evaluations using program data in Liberia and Malawi14,15 and quasi experimental studies in Ghana and Zambia,21 Rwanda,16 and Togo22 tested the effects of this model. The studies in Liberia,14 Rwanda,16 and Togo22 found a statistically significant increase in contraceptive use with no change in use of immunization services in Rwanda and Togo, and an increase in the administration of Penta1 and Penta3 vaccinations in pilot sites in Liberia. In Ghana and Zambia, the intervention did not lead to a statistically significant increase in contraceptive uptake and data on the effect on immunization services was not collected. Process data from Ghana and Zambia indicated that the model was not implemented as planned. In Zambia, family planning information was often given in group talks rather than one-on-one, and in Ghana, messages were not delivered consistently.21

- Combined Service Provision Plus Referral: This model entails the availability of co-located, same-day or follow-up family planning services for methods available at the site during routine immunization visits plus the provision of offsite referrals for methods not available at the facility. A Nepal operations research study found that this model successfully increased access to family planning information and counseling for women who attended immunization services without a negative impact on immunization uptake.23 Additionally, in this model the service provision may also happen in the community (outside of health facilities), helping to address access barriers by bringing services closer to clients. This model was also successfully implemented in Malawi where paid community health workers who were linked to primary care facilities provided both immunization services and family planning counseling and short-acting methods, and made referrals for long-acting and permanent methods.15

- Single Service Provision Plus Referral: This model, which involves offsite referrals or referrals requiring a follow-up visit at the same location, may be most appropriate where co-located, same-day services are not feasible. A study in Egypt tested this model finding increases in family planning uptake.24

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

Based on programmatic experience, the following strategies can help facilitate successful integration of family planning and immunization services.

- Conduct formative research prior to designing the integrated approach. This is critical to ensure a service delivery model that addresses contextual factors (e.g., gender norms and beliefs around postpartum abstinence, PPFP, privacy, and client preferences). It is also key to designing effective communication tools to enhance service quality. Formative research should explore the system context including infrastructure, client flow, privacy, provider workload, and job descriptions. For example, when exploring options to integrate family planning into well-attended immunization sessions in Bangladesh, the need for an additional cadre to be present was revealed. This also highlights the importance of understanding such human resources considerations from the outset.

- Design integrated services with systems in mind. Deliberate modifications to existing systems are necessary, including revising job descriptions for providers, supervisors, and other staff; reorganizing client flow and other aspects of service delivery; ensuring contraceptive and vaccine commodities are available; ensuring that systems track the number of referrals from one service to the other; conducting initial, refresher, on-the-job training and/or mentoring; and providing job aids with tasks and standards for integrated services.

- Design integrated services to avoid negatively affecting immunization. Ideally, integration will create “win-win” outcomes for both immunization and family planning services to foster buy-in. Integration of immunization into family planning services can benefit immunization programs by providing additional opportunities to reach zero-dose and under-immunized infants, children, and communities.

- Consider additional integration of family planning and immunization services with other health services to holistically address client needs. Integrating in immunization visits may be even more effective at encouraging PPFP use by 12 months postpartum if PPFP is discussed during pregnancy and/or at the time of birth.Thus, it is important to consider implementing family planning and immunization integration concurrently with immediate PPFP when possible (see HIP on immediate PPFP). Also, in Kenya, integrated approaches to reach pastoralist communities living in remote areas include a cross-sectoral, “one health” approach offering family planning/reproductive health and maternal and child care along with veterinary care for nomadic populations at watering points, and mobile outreach to serve remote locales. Observed benefits include reduction in distances traveled by clients, increased turnout, increased immunization coverage, and increased uptake of family planning.25,26

- Do not integrate family planning services into mass vaccination campaigns. These campaigns often occur episodically, are often chaotic in nature, are highly donor-dependent, and typically disease-specific. Family planning provision requires ongoing services, including counseling to address side effects, method switching (if desired), resupply of methods, and other follow-up. Provision of family planning education is also not appropriate during mass vaccination campaigns because experience shows challenges with lack of privacy for family planning counseling and a risk of misinformation being circulated.

- Keep family planning messages simple and reinforce provider communication skills via

training, job aids, and on-site mentoring for vaccinators. Some vaccinators may lack effective communication skills. In Ethiopia, for example, a study in the Benishangul-Gumuz region concluded

that vaccinators do not communicate all key immunization messages to caregivers and need interpersonal communication training to improve their skills and practice.27 To gain the skills and confidence to provide family planning information or conduct screening or referrals, vaccinators

should receive training, on-site coaching, and user-friendly job tools and job aids. - Consider systematic screening. Systematic screening is an evidence-based approach to comprehensively assess clients’ needs in a single visit using a standardized checklist. Evidence indicates that systematic screening helps to increase family planning uptake when used at facilities28 and communities.29 Systematic screening can lead to increased referrals from immunization to family planning.30

- Establish straightforward referral systems that facilitate client access to family planning services. For intra-facility or cross-unit collaboration, there should be options for both same-day and different-day referrals. Same-day referrals may increase convenience for some clients, but others may prefer to return on a different day out of privacy concerns or because they want to discuss family planning with their partner. When offering same-day services, encourage providers to confirm that mothers receive both family planning and immunization through simple measures such as jointly comparing registers for specific periods on a regular basis.18 Tracking referrals can involve simple paper tallies/dashboards to create feedback loops between originating and receiving providers.

- Assess the acceptability of integrated services in open air or outreach sites. In some contexts, integrated service in the open may not be acceptable due to community norms and privacy concerns. In Liberia, for example, greater privacy with screens in fixed facilities reduced stigma of

family planning use in context of postpartum abstinence norms and ensured women’s confidentiality as they made decisions about family planning use.14 That program did not include outreach sites for this reason.31 Elsewhere, privacy screens or alterations to client flow to increase confidentiality can help to address any client concerns.18,32 - Ensure a clearly defined client flow to provide both services within a specified window of time during outreach services. An evaluation of an integrated outreach program in Malawi found that improving client flow increased efficiency when handling a high volume of clients, improved community health worker (CHW) confidence, and resulted in more consistent documentation.33

- Ensure outreach services are well staffed. Increase the number of providers on anticipated busy days such as market days to avoid having long wait times. Also, consider having CHWs rotate positions at different service points during outreach services to offer both family planning and immunization services side-by-side to maintain proficiency in providing both services. Experience in Malawi showed that sufficient numbers of CHWs supported by the addition of community volunteers were key factors in providing integrated services.33

- Tailor integrated services to address client needs using an iterative, data-based, team-driven process. Tailoring services requires a dynamic, data-driven, team-based process that should be centered on information/data gathered from various sources including routine monitoring and evaluation, supportive supervision, input from clients, community leaders, and staff from different departments and cadres. Data-driven problem identification and team engagement will help to generate service provider buy-in and ownership to foster effective follow through. An assessment of family planning and immunization integration in Benin, for example, emphasized the importance of monitoring progress to address emerging challenges.32 Tailored approaches may result in several models being used in one setting to address the specific needs of underserved populations(e.g., adolescents, young married couples, pastoralist communities).

- Monitor integration’s impact on both family planning and immunization services and outcomes. Ongoing monitoring and supportive supervision can uncover additional constraints to integration of services. Avoiding negative impacts on immunization outcomes is essential to ensure collaboration.

Indicators

The following indicators are proposed for the measurement of family planning and immunization integration practices across programs:

- Number/percent of service delivery points that integrate family planning services during immunization visits disaggregated by health facility or outreach service delivery point. (Family planning services should include provision of contraceptive services and methods that goes beyond merely providing family planning information.)

- Number/percent of women attending routine immunization services who follow through on a family

planning referral from a vaccinator.

Priority Research Questions

- What are feasible and validated indicators to routinely monitor the integration of family planning and immunization without creating extra workload for health care providers and other staff?

- Does integration lead to cost savings or other efficiencies in terms of organization of care or deployment of staff resources in various settings?

- What are some key considerations to make family planning and immunization integrated services responsive to adolescent needs (e.g., to address the specific needs of adolescents and youth who are first-time parents)?

- What integration models are more effective in different contexts? How is the success or failure of integrated service delivery affected by contextual factors within the service setting and community?

- Family Planning and Immunization Integration Toolkit https://toolkits.knowledgesuccess.org/toolkits/family-planning-immunization-integration

- Key Considerations for Monitoring and Evaluating Family Planning (FP) and Immunization Integration Activities https://toolkits.knowledgesuccess.org/sites/default/files/FP%20Immunization%20Monitoring%20and%20Evaluation%20Briefer_0.pdf

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Programming Strategies for Postpartum Family Planning. WHO; 2020. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/ppfp_strategies/en/

- Moore Z, Pfitzer A, Gubin R, Charurat E, Elliott L, Croft T. Missed opportunities for family planning: an analysis of pregnancy risk and contraceptive method use among postpartum women in 21 low- and middle-income countries. Contraception. 2015;92(1):31-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2015.03.007

- Swaminathan A, Fell DB, Regan A, Walker M, Corsi DJ. Association between interpregnancy interval and subsequent stillbirth in 58 low-income and middle-income countries: a retrospective analysis using Demographic and Health Surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(1):e113-e122. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30458-9

- Nisha MK, Alam A, Islam MT, Huda T, Raynes-Greenow C. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with short and long birth intervals in Bangladesh: evidence from six Bangladesh Demographic and Health Surveys, 1996-2014. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e024392. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024392

- Brown W, Ahmed S, Roche N, Sonneveldt E, Darmstadt GL. Impact of family planning programs in reducing high-risk births due to younger and older maternal age, short birth intervals, and high parity. Semin Perinatol. 2015;39(5):338-344. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2015.06.006

- Kozuki N, Walker N. Exploring the association between short/long preceding birth intervals and child mortality: using reference birth interval children of the same mother as comparison. BMC Public Health. 2013;13 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S6

- Singh A, Singh A, Thapa S. Adverse consequences of unintended pregnancy for maternal and child health in Nepal. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(2):NP1481-NP1491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539513498769

- Bahk J, Yun SC, Kim YM, Khang YH. Impact of unintended pregnancy on maternal mental health: a causal analysis using follow up data of the Panel Study on Korean Children (PSKC). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0505-4

- Immunization coverage. World Health Organization. July 15, 2021. 2020. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage

- World Health Organization (WHO). Immunization Agenda 2030: A Global Strategy to Leave No One Behind. WHO; 2020. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.who.int/immunization/immunization_agenda_2030/en/

- Department for Internal Development (DFID). Choices for Women: Planned Pregnancies, Safe Births and Healthy Newborns: The UK’s Framework for Results for Improving Reproductive, Maternal and Newborn Health in the Developing World. DFID; 2010. Accessed August 6, 2021. https:// assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/ system/uploads/attachment_data/file/67640/RMNH-framework-for-results.pdf

- WHO Recommendations for Routine Immunization – Summary Tables. World Health Organization; 2020. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://www.who.int/ immunization/policy/immunization_tables/en/

- FHI 360/PROGRESS. Postpartum Family Planning: New Research Findings and Program Implications. FHI 360; 2012. Accessed August 6, 2021. http:// www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/ Postpartum%20Family%20Planning.pdf

- Cooper CM, Fields R, Mazzeo CI, et al. Successful proof of concept of family planning and immunization integration in Liberia. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(1):71-84. https://doi.org/10.9745/ GHSP-D-14-00156

- Cooper CM, Wille J, Shire S, et al. Integrated family planning and immunization service delivery at health facility and community sites in Dowa and Ntchisi districts of Malawi: a mixed methods process evaluation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijerph17124530

- Dulli LS, Eichleay M, Rademacher K, Sortijas S, Nsengiyumva T. Meeting postpartum women’s FP needs through integrated FP and immunization services: results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial in Rwanda. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4(1):73-86. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00291

- Ryman TK, Wallace A, Mihigo R, et al. Community and health worker perceptions and preferences regarding integration of other health services with routine vaccinations: four case studies. J Infect Dis. 2012;205 Suppl 1:S49-S55. https://doi.org/10.1093/ infdis/jir796

- Nelson AR, Cooper CM, Kamara S, et al. Operationalizing integrated immunization and family planning services in rural Liberia: lessons learned from evaluating service quality and utilization. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(3):418-434. https://doi. org/10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00012

- Hounton S, Winfrey W, Barros AJ, Askew I. Patterns and trends of postpartum family planning in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Nigeria: evidence of missed opportunities for integration. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:29738. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.29738

- Derso T, Biks GA, Yitayal M, et al. Prevalence and determinants of modern contraceptive utilization among rural lactating mothers: findings from the primary health care project in two northwest Ethiopian districts. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):67. https://bmcwomenshealth. biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-020- 00933-7

- Vance G, Janowitz B, Chen M, et al. Integrating family planning messages into immunization services: a cluster-randomized trial in Ghana and Zambia. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(3):359-366. https://doi. org/10.1093/heapol/czt022

- Huntington D, Aplogan A. The integration of family planning and childhood immunization services in Togo. Stud Fam Plann. 1994;25(3):176-183.

- Phillipson R. Case Study 5: Integration of Expanded Program on Immunisation and Family Planning Clinics: Value and Money Study. Kalikot Operational Research Pilot, 2012-2013. Nepal Health Sector Support Programme; 2013. Accessed August 6, 2021. http://www.nhssp.org.np/NHSSP_Archives/value/ Integrating_FP_within_the_EPI_august2013.pdf

- Ahmed AA, Nour SA, Genied AS, Mostafa NE. Impact of postpartum family planning counseling on use of female contraceptive methods in upper Egypt. Zagazig Nurs J. 2013;9(2):15-30. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://znj.journals.ekb.eg/ article_38658_59a73c3104e4c3581dff5d9523a4a64c. pdf

- Griffith EF, Ronoh Kipkemoi J, Robbins AH, et al. A One Health framework for integrated service delivery in Turkana County, Kenya. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice. 2020;10:7. https://doi. org/10.1186/s13570-020-00161-6

- Mwakangalu Mtungu D, Mukami D, Kosgei S, Omari A. Integrating FP and reproductive health programs: lessons from Kenya. Knowledge SUCCESS. May 20, 2020. Accessed November 19, 2020. https://knowledgesuccess.org/2020/05/20/integrating-family-planning-and-reproductive-health-programs-lessons-from-kenya/

- Teshome S, Kidane L, Asress A, Alemu M, Asegidew B, Bisrat F. Quality of health worker and caregiver interaction during child vaccination sessions: a qualitative study from Benishangul-Gumuz region of Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2020;34(2):122-128. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://ejhd.org/index.php/ ejhd/article/view/2980

- Das NP, Shah U, Chitania V, et al. Systematic Screening to Integrate Reproductive Health Services in India. FRONTIERS Final Report. Population Council; 2005. Accessed August 6, 2021. https:// knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/cgi/viewcontent. cgi?article=1422&context=departments_sbsr-rh

- Balasubramaniam S, Kumar S, Sethi R, et al. Quasi-experimental study of systematic screening for family planning services among postpartum women attending village health and nutrition days in Jharkhand, India. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18(1):7. https://doi. org/10.5334/ijic.3078

- Charurat E, Bashir N, Airede LR, Abdu-Aguye S, Otolorin E, McKaig C. Postpartum Systematic Screening in Northern Nigeria: A Practical Application of FP and Maternal Newborn and Child Health Integration. ACCESS-FP; 2010. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://toolkits.knowledgesuccess.org/toolkits/ ppfp/postpartum-systematic-screening-northern-nigeria-practical-application-family-planning

- Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP). Family Planning and Immunization Integration Implementation Guide: Liberia. MCHIP; 2014. Accessed August 6, 2021. https://toolkits. knowledgesuccess.org/sites/default/files/liberia_fp_ immunization_integration_implementationguide_ final.pdf

- Erhardt-Ohren B, Schroffel H, Rochat R. Integrated family planning and routine child immunization services in Benin: a process evaluation. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24(6):701-708. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10995-020-02915-5

- Hamon JK, Krishnaratne S, Hoyt J, Kambanje M, Pryor S, Webster J. Integrated delivery of family planning and childhood immunisation services in routine outreach clinics: findings from a realist evaluation in Malawi. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):777. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020- 05571-1

Suggested Citation

Suggested citation: High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). Family Planning and Immunization Integration: Reaching postpartum women with family planning services. Washington, DC: USAID; 2021 Sep. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/family-planning-andimmunization-integration/

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments: This brief was written by: Maria A. Carrasco (USAID), Rebecca Fields (JSI), Linda Ippolito (Strategy2Impact, LLC), Erin Mielke (USAID), Katy Mimno (IntraHealth International), Anne Pfitzer (Jhpiego), Shannon Pryor (Save the Children), Kate Rademacher (FHI 360), and Deborah Samaila Hassan (JHU/CCP).

This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Anthony Arasio (Amref Health Africa-Kenya), Chris Morgan (Jhpiego), Folake Olayinka (USAID), Laura McGough (URC), Laura Nic Lochlainn (WHO), Linda Gutierrez, Lizzie Noonan, Melanie Yahner, Misozi Kambanje, Samir Sodha (WHO), Sara Stratton, Susan Otchere (World Vision). It was updated from a previous version published in July 2013, available here.

The World Health Organization/Department of Sexual Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHOFP Tools and Guidelines:

https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception.

The HIP Partnership is a diverse and results-oriented partnership encompassing a wide range of stakeholders and experts. As such, the information in HIP materials does not necessarily reflect the views of each co-sponsor or partner organization.

To engage with the HIPs please go to:

https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/engagewith-the-hips/.