Social Norms: Promoting community support for family planning

- Descriptive social norms are beliefs about what other people do. Example: “In our community, most adolescents are not having sex.”

- Injunctive social norms are beliefs about what other people approve or disapprove of. Example: “It is not acceptable for couples in our community to use contraception until they have had at least one son. If they do so, their parents may punish them.”

Background

An individual’s or couple’s decisions and behaviors around contraception and reproductive health are influenced not only by their individual knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes but also by informal and mostly unwritten rules of the communities where they live known as “social norms.”

Social norms define acceptable and appropriate actions within a given community or group. They are sustained and enforced by people whose opinions or behaviors matter to an individual (e.g., sexual partners, friends, peers, family members, religious or community leaders). These individuals are known as reference groups. Individuals who do not act in accordance with social norms may face sanctions, such as ostracism or lowering of status.1 Social norms that affect an individual’s or couple’s decisions and behaviors around contraception and reproductive health include norms related to who has the power to make decisions; when and how many children to have; who is allowed and when it is appropriate to engage in sexual activity; and who is allowed and when it is appropriate to seek health services.2

Some social norms change quickly, such as expectations and rules around the increasing use of mobile phones. Others are more persistent, such as the household roles that men and women are expected to play. Experts note that social norms can be particularly powerful in influencing behaviors among marginalized populations. For example, young people may be denied participation in critical life decisions in communities where adults are given decision-making power over adolescents.3 Individuals with more resources, such as higher education or economic status, are more likely to engage in desired behaviors that conflict with current social norms than those with fewer resources.4

Gender norms, a subset of social norms, are particularly important in sexual and reproductive health as they shape societal expectations of men and women and often consolidate power and resources among men and male-dominated institutions.5,6 Gender roles and inequalities subsequently influence health outcomes.7

Interventions that address social norms typically do one or more of the following: 1) identify the social norms and reference groups relevant to the behaviors of interest; 2) seek change at the community rather than individual level; 3) confront power imbalances such as those related to gender and age; and/or 4) create or reinforce positive norms to support healthy behaviors.8,9

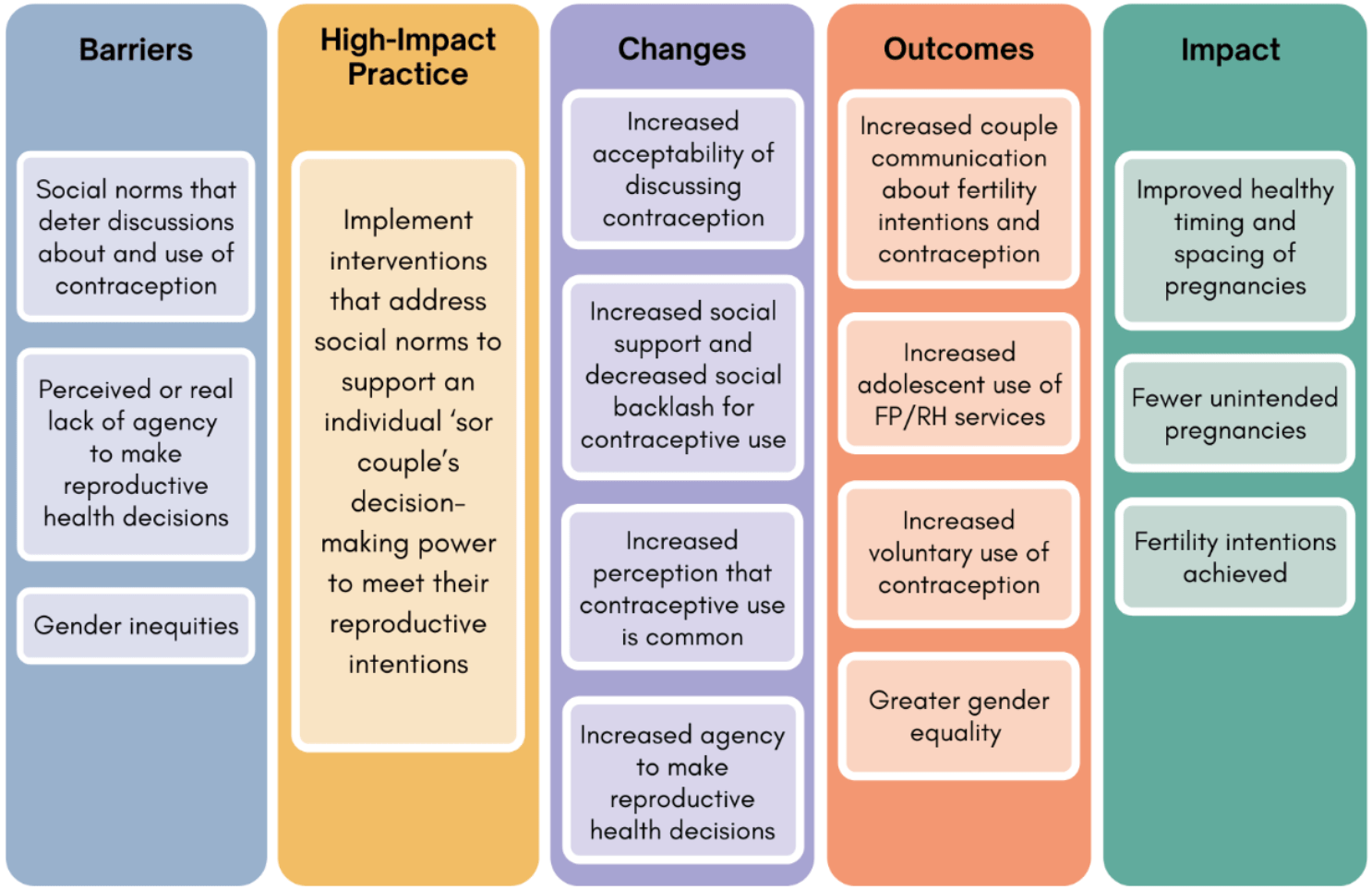

Implementing interventions that address social norms to support an individual’s or couple’s decision-making power to meet their reproductive intentions is one of several proven “high-impact practices in family planning” (HIPs) identified by the HIP partnership and vetted by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. This HIP brief together with the other two HIP briefs focusing on family planning social and behavior change (SBC) programs (couples’ communication and knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs) recognizes that factors influencing health behaviors exist on multiple levels, are interrelated, and extend beyond the individual. Together with the group of briefs on specific channels to reach audiences (mass media, community group engagement, digital health for SBC), they provide critical information on what works in family planning SBC programs. For more information about HIPs, see https://fphighimpactpractices.org/overview/.

Why is this practice important?

Social norms can inhibit an individual’s ability to act on their reproductive intentions. Social norms can overpower an individual’s preferences.10–12 In Kenya researchers found that men’s and women’s contraceptive use was influenced more by their perception of their social network’s approval of family planning than by their own approval of family planning.11

Social norms influence couples’ communication about family planning, which in turn influences contraceptive use. Couples who discuss family planning are more likely to use contraception.13,14 People who believe that other couples discuss family planning or who are encouraged by their networks to discuss family planning with their partners are more likely to report that they discuss family planning with their partner.15–17

Social norms affect individuals’ and couples’ decisions about when to have children. Studies in South Sudan, Ghana, and Ethiopia reported strong social pressure for newly-married couples to begin childbearing promptly. In light of this norm, couples were reluctant to use contraception until after they had had their first child and proven their fertility.18–21 Social norms that encourage parents to space their children for their health and strength affect contraceptive use, sexual activity, and childbearing decisions. In some contexts, social norms make contraceptive use more likely—particularly after a woman becomes a mother18—while in others they emphasize postpartum abstinence.22 Finally, in other contexts, social norms around couples having as many children as possible may be juxtaposed with established norms “which make spacing of pregnancies socially desirable, and from emerging norms on what entails taking good care of one’s children.”19(p11)

Social norms influence contraceptive use. Numerous studies have shown significant associations between social norms and contraceptive use among adults11,15,23,24 and young people.21,24,26,27 In several research studies, participants who reported social norms in their communities were favorable towards family planning were between two and four times as likely to use contraception.11,15,25 Social norms also affect the types of contraception that is used. For example, women in Bolivia reported using traditional methods of contraception rather than modern methods received from a health care provider because social norms discourage discussions about contraception, even with health care providers.27

Social norms can facilitate or hinder efforts to access good quality sexual and reproductive health care. For example, in Liberian communities with social norms that encourage child spacing by means of postpartum abstinence, postpartum women did not use the available family planning services because of a lack of privacy.22 Qualitative evidence from Laos, Ethiopia, and Vanuatu found that social norms around adolescent sexuality created barriers to adolescents’ use of sexual and reproductive health services, due to the reluctance of adolescents to seek services and disapproval from providers.28–30 In the study in Vanuatu, for example, adolescents reported feeling ashamed to access sexual and reproductive health services. Additionally, health care providers did not want to offer these services to adolescents and they scolded adolescents who accessed services for being sexually active.30 The Adolescent Responsive Contraceptive Services HIP brief notes the need to implement interventions to address social norms contributing to provider bias.31

What interventions address social norms to support an individual’s or couple’s decision-making power to meet their reproductive intentions?

Several SBC interventions have successfully addressed social norms and resulted in increased use of voluntary contraception (Table 1). These successful interventions have included multiple channels of communication, including reflective dialogues10,32–35; mass media32,35; interpersonal communication32,33,35; and an intervention sent via text messages.36

The interventions in Table 1 generally used multiple components to target individuals, couples/households, communities, and systems. Their use of multiple components aligns with the socioecological model.5 For example, in Nigeria, an intervention that sought to increase contraceptive use in urban areas trained hairdressers, barbers, and tailors to talk to their clientele on an individual and small-group basis. Mass media programs shared similar messages at the community level. Finally, to support norm change at the systems level, the project invested in health systems improvement ensuring family planning facilities were clean, welcoming, and had adequate commodities and equipment, and that providers and informational materials reinforced the messages used elsewhere in the campaign.35 Additional evidence from these multi-component interventions is needed to better understand which intervention components and what combinations are most effective in addressing family planning-related social norms and reaching family planning outcomes.

Experts believe that social norms have played a larger role in the success of SBC interventions than is shown through the studies in Table 1. SBC interventions in Egypt, India, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Senegal, and Uganda intentionally set out to address norms (per their design or theory of change) and succeeded in increasing voluntary contraceptive use but did not quantitatively measure or report social norm change (Appendix).37–41 Finally, it is widely believed that “telenovelas” (entertainment-education soap operas) were a key factor in changing social norms related to family size and contraceptive use in Latin America in the 1970–80s, but data on social norms were not collected in those contexts.42

Reflective dialogues are facilitated discussions among community members that encourage critical reflection, dialogue, and consensus about the social norms held in the community and how those norms affect the well-being of all members.

Table 1. Social norm-focused interventions within family planning programs that led to social norm change and contraceptive use

Country / Citation | Intervention Description | Invervention impact on | |

Social norms | Contraceptive use | ||

Benin / IRH 2017 & IRH 201615,32 | Social network mapping identified key influencers who were engaged in reflective dialogues about family planning-related norms. Community radio broadcasted the reflective dialogues. Influencers were encouraged to discuss new ideas and behaviors with their networks. Referrals to health providers were offered. | Men who heard the radio broadcasts were more likely to believe their peers use contraception (descriptive norm).✓ Men and women who had participated in a reflective dialogue were more likely to believe their peers approved of family planning (injunctive norm).✓ | The percentage of women who were using a contraceptive method increased.✓ Community members exposed to select package components were more likely to use a contraceptive method and to meet their family planning needs.✓ |

Niger / Challa et al., 201933; Shakya et al., 202125 | Community health workers conducted home visits to talk with couples. Reflective dialogues were held among small groups of couples and larger groups of community members regarding family planning and timing and spacing of pregnancies. | The young wives who participated in the intervention were more likely to report that their social networks would approve of family planning, a delay between marriage and first birth, and men who listen to their wives’ fertility preference (injunctive norms).✓ | Analysis with data at one point in time (i.e., cross-sectional analysis) revealed that the friends and family of the young wives in the intervention were more likely to report ever having used contraception, especially when they had heard about the program from the participants.✓ |

Zambia / Wegs et al. 201110 | Community health workers led reflective dialogues on gender and family planning. Satisfied family planning users served as role models. Health systems improvements were also made. | Women were more likely to report that their husbands approved of family planning (injunctive norm).✓ | There was an increase in the use of modern contraception for women. Contraceptive use among men decreased. |

Kenya / Wegs et al., 201634 | Influential community members led reflective dialogues on gender and family planning. Satisfied family planning users served as role models. Health systems improvements were also made. | The dialogues increased the perceived social acceptability of both family planning and couples’ communication (injunctive norms). | Women who participated in reflective dialogues more likely to use a modern contraceptive method.✓ |

Nigeria / Krenn et al., 201435 | Mass media, including radio and television, aimed to increase demand for family planning. Hairdressers, barbers, and tailors spoke with their clientele on an individual basis and facilitated small-group reflective dialogues. Health systems improvements were made. | The percentage of women who perceived peer support for (injunctive) and use of family planning (descriptive) increased.✓ With increased exposure to the intervention, women were more likely to report peer support for family planning (injunctive norm). | Use of modern contraceptives increased in most intervention areas.✓ The greater the number of intervention components that women were exposed to, the greater their contraceptive use. |

Palestine / McCarthy et al., 201636 | Up to three mobile phone text messages about contraception and reproductive health self-efficacy were sent daily. | Recipients of the intervention were more likely to report that they believed their friends would use family planning (descriptive norm).✓ | The use of effective contraception increased. Young women who received text messages were more likely to intend to use an effective method of contraception.✓ |

✓ Statistically significant

There are some SBC interventions implemented in Cote D’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria that were unable to show the intended shifts in social norms despite successfully changing family planning behaviors (Appendix).16,23,43 A lack of finding of an effect of an intervention in shifting norms could be either because norms take time to change and research projects are often implemented in short time periods or because of challenges with how norms were measured.

In fact, measurement challenges are a factor in the limited evidence available to demonstrate how interventions can successfully address family planning-related social norms.44,45 A lack of agreement on how to measure social norms, as well as the time and resources required to do so, are potential reasons for studies to not include social norm measures. It can also be difficult to identify, and thus measure, the social norms and/or reference groups with the strongest influence on desired behaviors. In addition, evaluations of SBC interventions are typically more focused on whether the intervention changed behavior than on understanding how the intervention worked. Thus, even when measured, it is difficult to determine which variable(s) (e.g., changes in knowledge, beliefs, social norms) led to the change in behavior.46 Doing formative research on the social norms and reference groups that most influence behavior, using those results in developing evaluation indicators, and using indicators of descriptive and injunctive norms (see Implementation Measures below) can help to mitigate some of these challenges.

How to do it: Tips for implementing interventions that address social norms

Identify the norms and the power dynamics underlying norms and behaviors. Program staff should work with communities to determine which norms influence the behavior/s of interest, who influences norms and behaviors (i.e., reference groups), and who enforces them.47 Careful attention also should be paid to power dynamics, including across genders, age groups, and individuals or groups with differing roles and status within the community. This initial exploration of social norms should seek to identify the full range of norms relevant to the desired behavior, including norms related to gender, sexuality, decision making, and use of health care services.

Ensure staff and facilitators have the training and skills to support community-led social norm processes. In reflective dialogues, the role of the facilitator is to create an inclusive and trusting environment in which community members can respectfully discuss social norms, while using his/her skills to probe for different points of view, prompt critical thinking, and manage tensions. To ensure that facilitator beliefs and unconscious biases do not unintentionally limit the ability of the community to set their own values or cause harm, staff and facilitators should engage in separate reflective dialogues and/or values clarification activities to explore their own beliefs.48

Create or reinforce positive social norms by modeling desired behavior(s). Modeling is a powerful tool to affect social norms. It can be done through mass and/or digital media, by engaging role models in reflective dialogues and other community events, and/or through testimonies or other storytelling approaches. Modeling demonstrates the process of accepting and acting on the desired behavior, conveys the benefits of practicing the behavior, and provides examples of how to resist norms and strengthen individual agency. The perception that other people, particularly others like them, are doing the same thing and/or approve of it, can increase positive norms and self-efficacy.

Anticipate, plan for, monitor, and mitigate pushback and unanticipated harmful effects. Challenging a social norm can lead to unintentional harm, with the potential for backlash that affects the well-being and safety of staff, facilitators, and community members and that can be detrimental to future interventions. Programs must maintain strong “do no harm” principles. This requires careful consideration of the complex sensitivities around social norms, as well as planning for ways to lessen risks for all involved, especially marginalized groups.47,49

Implementation Measurement

The measurement of social norms has evolved in the last decade, with experts now recommending measures of descriptive and injunctive social norms, and diffusion of social norms. As written below, these indicators would be measured through surveys, but could be adapted for use with qualitative methods such as focus group discussions. They can also be tailored to address behaviors other than contraceptive use, such as spacing births or discussing family planning with a partner, and to specific reference groups.

- Descriptive norm: Percent of intended audience who report that people in their reference group use a contraceptive method. (What others do)

- Injunctive norm: Percent of intended audience who report that their reference group would approve of them using contraception. (What others think I should do)

- Diffusion: Percent of intended audience who have discussed new family planning-related ideas or behaviors with others in their community.

Priority Research Questions

- Capturing evidence on how SBC interventions can address social norms and thus change family planning behaviors can be challenging, time-consuming, and costly. How do we best evaluate the effectiveness of interventions that address social norms?

- Most interventions with evidence showing that norms were successfully shifted included reflective dialogues. What other types of interventions (e.g., mass and digital media, advocacy for policy change) and what combinations of interventions can effectively address family planning-related social norms?

- Do interventions that address social norms lead to sustained changes in family planning behaviors by creating an environment in which contraceptive use is considered normal and approved of? And if so, how can programs accelerate diffusion of positive social norms to more quickly reach that “tipping point”?

Tools and Resources

- 20 Essential Resources on Social Norms and Family Planning. This collection of resources is for program planners, designers, and implementers who want to understand and measure social norms and incorporate social norm interventions into their work.

- The Advancing Learning and Innovation on Gender Norms (ALIGN) Platform. This website brings together resources on gender norms and creates a related community of practice; it includes many resources for family planning-related social norms.

- Getting Practical: Integrating Social Norms Into Social and Behavior Change Programs. This tool is for program planners, designers, and evaluators to address the gap between formative social norms research and the other phases of the program design cycle.

- A Taxonomy for Social Norms That Influence Family Planning in Ouagadougou Partnership Countries. This tool offers a simple classification system for social norms related to family planning. It can be used to help those who are new to social norms to quickly understand what norms in their community may look like.

- Social Analysis and Action (SAA) Global Implementation Guide. SAA is a facilitated process through which individuals explore and challenge the social norms and practices that shape their lives and health.

References

- Lundgren R, Uysal J, Barker K, et al. Social Norms Lexicon. Institute for Reproductive Health/Passages Project; 2021. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://irh.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Social-Norms-Lexicon_FINAL_03.04.21-1.pdf

- Breakthrough ACTION. A Taxonomy for Social Norms That Influence Family Planning in Ouagadougou Partnership Countries. Breakthrough ACTION; 2020. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Taxonomy-for-Social-Norms-OP-Countries.pdf

- Buller AM, Schulte CM. Aligning human rights and social norms for adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights. Reprod Health Matters. 2018;26(52):38–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2018.1542914

- Mayaki F, Kouabenan D. Social norms in promoting family planning: a study in Niger. South African J Psychol. 2015;45(2):249–259. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0081246315570356

- Pulerwitz J, Blum R, Cislaghi B, et al. Proposing a conceptual framework to address social norms that influence sexual and reproductive health. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(4S):S7–S9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.014

- Cislaghi B, Heise L. Gender norms and social norms: differences, similarities and why they matter in prevention science. Sociol Health Illn. 2020;42(2):407–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13008

- Heise L, Greene ME, Opper N, et al. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. Lancet. 2019;393(10189):2440–2454. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30652-X

- Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH). Identifying and Describing Approaches and Attributes of Norms-Shifting Interventions – Background Paper. IRH; 2019. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://irh.org/resource-library/identifying-and-describing-approaches-and-attributes-of-normative-change-interventions-background-paper/

- Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH). Toward Shared Meaning: A Challenge Paper on SBC and Social Norms. IRH; 2021. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://irh.org/resource-library/challenge-paper/

- Wegs C, Feyisetan B, Alaii J, Cheeba P, Mbewe F. Social and Behavior Change Communication to Address Family Planning Uptake in an Integrated Program in Zambia. FHI 360/C-Change Project; 2011.

- Dynes M, Stephenson R, Rubardt M, Bartel D. The influence of perceptions of community norms on current contraceptive use among men and women in Ethiopia and Kenya. Health Place. 2012;18(4):766–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.04.006

- Adongo PB, Phillips JF, Kajihara B, Fayorsey C, Debpuur C, Binka FN. Cultural factors constraining the introduction of family planning among the Kassena-Nankana of northern Ghana. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(12):1789–1804. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00110-x

- Rosen JE, Bellows N, Bollinger L, Plosky WD, Weinberger M. The Business Case for Investing in Social and Behavior Change for Family Planning. Population Council/Breakthrough RESEARCH; 2019. Accessed April 12, 2022. https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/20191211_BR_FP_SBC_Gdlns_Final.pdf

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Promoting Healthy Couples’ Communication to Improve Reproductive Health Outcomes. HIPs Partnership; 2021. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/couple-communication/

- Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH). Effects of a Social Network Diffusion Intervention on Key Family Planning Indicators, Unmet Need and Use of Modern Contraception: Household Survey Report on the Effectiveness of the Tékponon Jikuagou Intervention. IRH; 2016. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://irh.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Tekponon_Jikuagou_Final_Pilot_Report.pdf

- Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH); FHI 360. Transforming Masculinities/Masculinité, Famille, et Foi Intervention; Endline Quantitative Research Report. IRH/Center for Child and Human Development; 2020.

- Avogo W, Agadjanian V. Men’s social networks and contraception in Ghana. J Biosoc Sci. 2008;40(3):413–429. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932007002507

- Velonjara J, Crouthamel B, O’Malley G, et al. Motherhood increases support for family planning among Kenyan adolescents. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018;16:124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2018.03.002

- Kane S, Kok M, Rial M, Matere A, Dieleman M, Broerse JE. Social norms and family planning decisions in South Sudan. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3839-6

- Adams MK, Salazar E, Lundgren R. Tell them you are planning for the future: gender norms and family planning among adolescents in northern Uganda. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123(suppl 1):e7–e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.07.004

- Addis Continental Institute of Public Health (ACIPH). Improving Adolescent Reproductive Health and Nutrition Through Structural Solutions in West Hararghe, Ethiopia (Abdiboru Project). ACIPH; 2020. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/improving-adolescent-reproductive-health-and-nutrition-through-structural-solutions-west

- Nelson AR, Cooper CM, Kamara S, et al. Operationalizing integrated immunization and family planning services in rural Liberia: lessons learned from evaluating service quality and utilization. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(3):418–434. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00012

- Silva M, Komlan E, Dougherty L. Monitoring the Quality Branding Campaign Confiance Totale in Côte d’Ivoire. Breakthrough RESEARCH Technical Report. Population Council; 2021. Accessed April 12, 2022. http://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/BR_Confiance_Totale_Rprt.pdf

- Agha S, Morgan B, Archer H, Paul S, Babigumira JB, Guthrie BL. Understanding how social norms affect modern contraceptive use. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1061. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11110-2

- Shakya HB, Challa S, Nouhou AM, Vera-Monroy R, Carter N, Silverman J. Social network and social normative characteristics of married female adolescents in Dosso, Niger: associations with modern contraceptive use. Glob Public Health. 2021;16(11):1724–1740. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1836245

- Sedlander E, Rimal RN. Beyond individual-level theorizing in social norms research: how collective norms and media access affect adolescents’ use of contraception. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(4S):S31–S36. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jadohealth.2018.12.020

- Schuler SR, Choque ME, Rance S. Misinformation, mistrust, and mistreatment: family planning among Bolivian market women. Stud Fam Plann. 1994;25(4):211–221. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137904

- Sychareun V, Vongxay V, Houaboun S, et al. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy and access to reproductive and sexual health services for married and unmarried adolescents in rural Lao PDR: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):219. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1859-1

- Birhanu Z, Tushune K, Jebena MG. Sexual and reproductive health services use, perceptions, and barriers among young people in southwest Oromia, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018;28(1):37–48. https://dx.doi.org/10.4314%2Fejhs.v28i1.6

- Kennedy EC, Bulu S, Harris J, Humphreys D, Malverus J, Gray NJ. “Be kind to young people so they feel at home”: a qualitative study of adolescents’ and service providers’ perceptions of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in Vanuatu. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:455. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-455

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Adolescent-Responsive Contraceptive Services: Institutionalizing Adolescent-Responsive Elements to Expand Access and Choice. HIPs Partnership; 2021. Accessed April 11, 2022. http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/adolescent-responsive-contraceptive-services

- Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH). Tékponon Jikuagou: Final Report. IRH; 2017.

- Challa S, DeLong SM, Carter N, et al. Protocol for cluster randomized evaluation of reaching married adolescents – a gender-synchronized intervention to increase modern contraceptive use among married adolescent girls and young women and their husbands in Niger. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0841-3

- Wegs C, Creanga AA, Galavotti C, Wamalwa E. Community dialogue to shift social norms and enable family planning: an evaluation of the family planning results initiative in Kenya. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153907. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153907

- Krenn S, Cobb L, Babalola S, Odeku M, Kusemiju B. Using behavior change communication to lead a comprehensive family planning program: the Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2(4):427–443. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00009

- McCarthy OL, Zghayyer H, Stavridis A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an intervention delivered by mobile phone text message to increase the acceptability of effective contraception among young women in Palestine. Trials. 2019;20(1):228. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3297-4

- Hutchinson PL, Meekers D. Estimating causal effects from family planning health communication campaigns using panel data: the “your health, your wealth” campaign in Egypt. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e46138. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046138

- Daniel EE, Masilamani R, Rahman M. The effect of community-based reproductive health communication interventions on contraceptive use among young married couples in Bihar, India. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2008;34(4):189–197. https://doi.org/10.1363/ifpp.34.189.08

- Subramanian L, Simon C, Daniel EE. Increasing contraceptive use among young married couples in Bihar, India: evidence from a decade of implementation of the PRACHAR project [published correction appears in Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018 Oct 4;6(3):617]. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018;6(2):330–344. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00440

- Lusambili AM, Wisofschi S, Shumba C, et al. A qualitative endline evaluation study of male engagement in promoting reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health services in rural Kenya. Front Public Health. 2021;9:670239. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.670239

- Shattuck D, Kerner B, Gilles K, Hartmann M, Ng’ombe T, Guest G. Encouraging contraceptive uptake by motivating men to communicate about family planning: the Malawi Male Motivator project. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1089–1095. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300091

- Bertrand JT, Ward VM, Santiso-Gálvez R. Family Planning in Latin America and the Caribbean: The Achievements of 50 Years. MEASURE Evaluation; 2015. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/tr-15-101.html

- Jah F, Connolly S, Barker K, Ryerson W. Gender and reproductive outcomes: the effects of a radio serial drama in Northern Nigeria. Int J Popul Res. 2014:326905. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/326905

- Costenbader E, Lenzi R, Hershow RB, Ashburn K, McCarraher DR. Measurement of social norms affecting modern contraceptive use: a literature review. Stud Fam Plann. 2017;48(4):377–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12040

- Costenbader E, Cislaghi B, Clark CJ, et al. Social norms measurement: catching up with programs and moving the field forward. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(4S):S4–S6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.001

- Carrasco MA, Mickler AK, Young R, Atkins K, Rosen JG, Obregon R. Behavioural and social science research opportunities. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(11):834–836. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.285370

- Cislaghi B, Heise L. Theory and practice of social norms interventions: eight common pitfalls. Global Health. 2018;14(1):83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0398-x

- Kambou SD, Magar V, Gay J, et al. Walking the Talk: Inner Spaces, Outer Faces, a Gender and Sexuality Initiative. Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, Inc./International Center for Research on Women; 2006. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Walking-the-Talk-Inner-Spaces-Outer-Faces-A-Gender-and-Sexuality-Initiative.pdf

- Igras S, Kohli A, Bukuluki P, Cislaghi B, Khan S, Tier C. Bringing ethical thinking to social change initiatives: why it matters. Glob Public Health. 2021;16(6):882–894. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1820550

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). Social Norms: Promoting community support for family planning. Washington, DC: USAID; 2022 May. Available from: https://www. fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/social-norms/

Acknlowedgements

This brief was written by: Maria Carrasco (USAID), Christine Galavotti (BMGF), Jennifer Gayles (Save the Children), Rebecka Lundgren (Center on Gender Equity and Health – University of California San Diego), Collins Otieno (Planned Parenthood Global), Shefa Sikder (CARE), Caitlin Thistle (USAID), Claudia Vondrasek (JHU-CCP), and Lucy Wilson (Independent Consultant).

This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Shittu Abdu-Aguye (JHU-CCP), Arzum Ciloglu (JHU-CCP), Elizabeth Costenbader (FHI 360), Leanne Dougherty (Population Council), Sally Griffin, Xaher Gul (Pathfinder International), Sherry Hutchinson (Population Council), Nrupa Jani (Population Council), Amanda Kalamar (Population Council), Joan Kraft (USAID), Rachel Lenzi (FHI 360), Lara Lorenzetti (FHI 360), Aramanzan Madanda (CARE), Shawn Malarcher (USAID), Donna McCarraher (FHI 360), Courtney McLarnon (Georgetown IRH), Alice Payne Merritt (JHU-CCP), Sarah Nabukera (Pact), Catherine Packer (FHI 360), Stephanie Perlson (PRB), Laura Reichenbach (Population Council), Rajiv Rimal (Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health), Boniface Sebikali, Barbara Seligman (PRB), Martha Silva (Population Council), Linda Sussman (USAID), Youssef Tawfik, John Townsend (Population Council), Samantha Wilde (Banyan Global), Rachel Yavinsky (Population Council).

The World Health Organization/Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception

The HIP Partnership is a diverse and results-oriented partnership encompassing a wide range of stakeholders and experts. As such, the information in HIP materials does not necessarily reflect the views of each co-sponsor or partner organization.

To engage with the HIPs please go to: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/engage-with-the-hips/