Social Franchising: Improving quality and expanding contraceptive choice in the private sector

Background

A social franchise is a network of private-sector health care providers that are linked through agreements to provide socially beneficial health services under a common franchise brand.1 This type of network can be particularly important for expanding availability and improving the quality of family planning services in the private sector, particularly for provider-dependent methods such as intramuscular injectable contraceptives, contraceptive implants, and intrauterine devices (IUDs). This brief describes the potential impact of social franchising on key family planning outcomes. It also provides useful guidance on how social franchising can be used to increase access to high-quality family planning products and services.

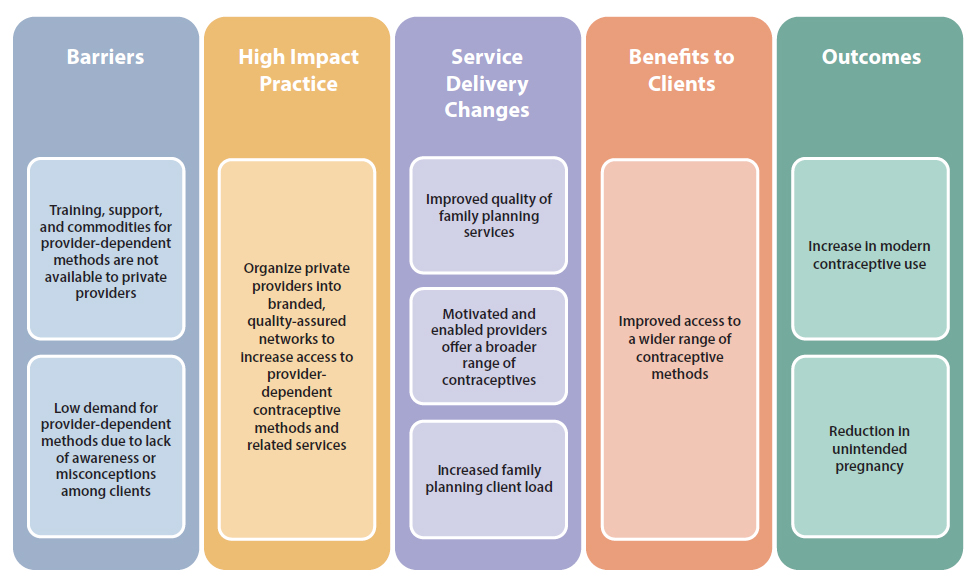

Even though private providers are a common source of family planning services, many do not offer a full range of methods. Independent private providers may lack training and support to offer provider-dependent methods; they may find commodities for these methods prohibitively expensive and accessing free or subsidized stocks difficult and time consuming; and some note low demand for these methods among their clientele (see Figure 1). Nonetheless, failure to offer these methods within the range of services available represents a missed opportunity to leverage existing health care infrastructure and client health-seeking behaviors to expand access to a broad range of family planning methods.

Most social franchise networks are managed by a nongovernmental organization (NGO), referred to as the “franchisor.” The franchisor provides several benefits to franchisees, which often include clinical training, supportive supervision, and quality assurance mechanisms; business skills development and mentoring; access to affordable contraceptive and other health commodities; and support for family planning awareness raising and demand creation within the franchisees’ catchment areas.2-4 Franchisors often brand franchises to signal to clients quality and affordability at franchisee clinics.

Social franchising is one of several promising High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs) identified by a technical advisory group of international experts. A promising practice has limited evidence, with more information needed to fully document implementation experience and impact. The advisory group recommends that such promising interventions be promoted widely, provided they are implemented within the context of research and are carefully evaluated in terms of both impact and process. For more information about HIPs, see www.fphighimpactpractices.org/overview.

What challenges can social franchising help countries address?

Social franchising can improve the quality of clinical family planning services delivered by private-sector providers. In many countries, the quality of health care in the private sector varies substantially among providers, and governments struggle to effectively provide stewardship and oversight of mixed health systems.5 A systematic review found that franchised clinics typically score higher on quality ratings than non-franchised private clinics,4 although an additional review reported mixed results.6 With support from the franchisor, franchisee clinics have demonstrated that they can improve clinical quality standards, including high-quality counseling, provider competence, infection prevention, and clinical governance.7 Beyeler et al. concluded that “franchising may be a particularly useful strategy in areas where a large unregulated private sector provides the majority of health services.”4

Social franchising can bring more family planning clientele to participating private-sector clinics. Several studies show that clinics experience a rise in family planning visits after joining a franchise. Studies in Myanmar and Vietnam documented an increase of approximately 40% in client loads of franchisee clinics compared with volumes prior to joining the franchise network.8,9 Franchisee providers in Ghana and Kenya cited increases in family planning client flow as one of several main benefits of social franchise network membership.10 At least one study indicates, however, that increases in client load may be due to more frequent use of services by individuals rather than an increase in total number of clients.9

Social franchising supports access to and voluntary use of long-acting and permanent methods. Studies in Kenya and Pakistan show that women living in catchment areas served by a social franchise facility are more likely to be using a long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) or permanent method than women in areas without a social franchise.11,12 Routine service data from one large global franchisor showed that in 2014 nearly 70% of methods provided by social franchisee clinics were implants and IUDs, and nearly 50% of clients who adopted a method at their visit and who had not been using a modern method for at least three months prior to their visit had chosen an implant or IUD.7

Social franchising can support coordination of independent private providers with public health systems in support of goals like Universal Health Coverage. A key component to most family planning social franchise networks is access to family planning commodities through government stocks. The process, which would be too difficult for individual private providers to successfully navigate, is managed by the franchisor. Accessing free or subsidized commodities enables franchisees to make a reasonable profit margin from family planning services while keeping service prices affordable for the client. These types of linkages between franchise networks and Ministries of Health are also a step toward better collaboration between public and private health sectors. Experts believe that social franchise networks can act as an “aggregator” of the private sector to, for example, link franchisees to national health insurance programs. In the Philippines, midwife-operated social franchisees are supported to become accredited by PhilHealth, the national health insurance program, to deliver contraceptives (and other services such as safe delivery) to insured clients, with reimbursement provided by PhilHealth.13 Similar coordination is taking place in other countries including Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria.

What is the evidence that social franchising programming is high impact?

Social franchise networks deliver family planning services in a wide variety of contexts. There are more than 70 known family planning franchise programs worldwide, largely in Africa and South/Southeast Asia. Large social franchise networks are being implemented in middle-income countries such as India and South Africa as well as in fragile, less-developed markets such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mali.14 The network size varies, with some programs reaching significant scale. In Kenya, for example, internal program data from indicate that more than 750 social franchise facilities operate countrywide (internal MSI and PSI program data). Bangladesh includes more than 6,300 franchised facilities that serve over 1.3 million clients.14

Evidence is unclear as to whether social franchising contributes to population-level increases in contraceptive use.4 Experimental studies in India,15 Nepal,16 and Pakistan12 found no statistically significant difference in contraceptive prevalence in communities before and after franchisee facilities were introduced. In Kenya, multivariate analysis found that women in communities with social franchisees were no more likely to be modern contraceptive users than women living in communities without social franchisees.11 Table 1 provides additional details of these studies.

Social franchising’s contribution to increasing contraceptive prevalence was estimated using the Impact 2 model17 with data from a large international NGO that operates social franchise networks across the world (unpublished data from MSI and Avenir Health, 2017). Between 2012 and 2016, the median contribution to increasing national contraceptive prevalence among the 6 social franchise networks that participated in national health insurance or voucher programs was 0.88 percentage points (range: 0 to 1.59 percentage points). Among the 7 social franchise networks that did not participate in NHI or voucher programs, the median contribution was lower, at 0.39 percentage points (range: 0.10 to 2.59 percentage points). The social franchise network in Mali had the largest impact, with contraceptive prevalence increasing by an estimated 2.59 percentage points over 4 years. The program in Mali does not include vouchers nor does it participate in a national health insurance program.

There may be greater impact when combining social franchising with a voucher program. A study in Pakistan documented a net increase of 23 percentage points in modern contraceptive use in districts served by social franchise facilities participating in a voucher program.2

| Country (Sample Size) | Intervention | Modern Contraceptive Use | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uttar Pradesh, India15 | Social franchise | −3 percentage point net effect | This social franchise model was not effective in improving the quality and coverage of maternal health services, including family planning at the population level. |

| Kenya11 (N=5269) |

Social franchise | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) 0.95 (0.7, 1.2) | There was no statistically significant difference in modern contraceptive use in the community with social franchise clinics compared with the community without. |

| Nepal16 (N=1907) |

Social franchise | +13 percentage point net effect | Modern contraceptive prevalence increased from 45% to 50% in communities with social franchisees while control communities experienced a decrease in contraceptive use from 56% to 48%, resulting in a net change in contraceptive use of 13 percentage points. However, this change in use was not statistically significant (P=0.067). |

| Pakistan12 (N=5338) |

Social franchise | −1.5 percentage point net effect | Modern contraceptive use increased at nearly the same rate in the intervention (+4.7 percentage points) and control (+6.2 percentage points). |

| Pakistan2 (N=8995) |

Social franchise + voucher | +23 percentage point net effect | Modern contraceptive use increased significantly in intervention communities, from 18% to 43%, while control communities showed little change (24% to 26%). |

Social franchising helps private providers incorporate adolescent-friendly contraceptive services. Studies in Kenya and Madagascar demonstrate that training franchisees on youth-friendly principles and including young people in the marketing strategy can increase modern contraceptive use, including the voluntary use of LARCs among youth—both male and female.11,18,19 (See related HIP brief on Adolescent-Friendly Contraceptive Services.)

The cost-effectiveness of family planning social franchise networks remains undetermined.

Studies in Ethiopia, Myanmar, and Pakistan have examined the cost-effectiveness of social franchising.20,21 However, differences in study approaches, methodologies, and measures make it difficult to draw generalizable conclusions from these works. Efforts are underway to standardize methods and approaches for more conclusive results.

How to do it: Tips from the implementation experience

The following are common considerations for successful implementation of social franchising.

Assess health market conditions. Social franchising is more likely to deliver intended results in markets where certain conditions exist, such as when the private sector is already delivering a substantial portion of health services and when the government is supportive of private-sector partnerships (see Box 1).

Seek opportunities to engage large social franchise networks and geographic coverage. Larger networks benefit more from economies of scale with certain activities, for example, in procurement of health commodities and supplies, demand-side interventions, and marketing support. Additionally, a degree of regional focus allows supportive supervision to be conducted in a more cost-effective manner and supports cross-network learnings and referrals (i.e., interaction between franchisees).

Recruit franchisees selectively. Successful franchisees must see value in franchise network membership, be motivated to expand their contraceptive service offerings, and be open and responsive to supportive supervision. With attention to equity, prospective franchisees should be located in lower-income catchment areas.

Identify franchisees that have underutilized capacity to maximize health impact. Prospective franchisees should have the ability to increase the range and quality of services they offer and the capacity to serve more clients. De-franchising—that is, removing a facility from the franchise network—is sometimes necessary when franchisees are unable or unwilling to improve their quality to meet clinical standards or other franchise requirements. However, high rates of de-franchising point to poor initial franchisee selection and/or failure of the franchisor to deliver inputs that are valuable to the franchisee.

Clarify expectations and commitments between franchisor and franchisee at the outset. A written agreement between franchisor and franchisee sets out defined quality standards, expected services available, and roles and responsibilities between parties. Agreements may also include the price guidance at which these services should be offered.

Take into account client service volumes of each franchisee. Franchisee providers must serve enough clients and deliver enough services to maintain their technical skills and benefit from network-related increases in revenue. Furthermore, since ongoing supportive supervision of franchisees is resource-intensive, client and service volume are key for the intervention to be cost-effective. Many franchisors offer support to franchisees with clinic branding, marketing of franchised services, and family planning awareness raising at the community level. These interventions can help promote the availability of new services and grow and maintain family planning client volumes.

Consider offering a broad range of services as part of the franchise package. IUD and implant services are the most commonly added family planning services when a clinic joins a family planning social franchise network. Currently, social franchising is not a major channel for expanding access to voluntary permanent methods because franchisee clinics tend to be staffed by mid-level providers who, in most contexts, are not permitted to deliver tubal ligation and vasectomy. However, looking forward, social franchising may present increased opportunities for permanent methods, especially in countries with task-shifting policy changes underway. Including non-family planning services in the package of franchised services can also present a strategic opportunity. Franchisees may be better positioned for inclusion in national health insurance programs when a broader package of services is offered.

Meet the needs and preferences of female and male clients under age 25 by including youth-friendly contraceptive services. Young clients may already prefer accessing family planning from the private sector, where many may perceive greater anonymity and privacy. However, franchisors can proactively support franchisee providers to better reach and serve young clients through organized media campaigns, use of social media, flexible clinic hours, and provider training on how to deliver confidential, nonjudgmental services. (See related HIP brief on Adolescent-Friendly Contraceptive Services.)

Consider demand-side subsidies, such as vouchers or participation in health insurance, to effectively serve youth and clients from the lowest income quintiles. Most frequently, clients of social franchisees pay a family planning service fee, although these prices are typically subject to price guidance by the franchisor to maintain affordability. To reach the lowest-wealth quintile clients and young people with limited purchasing power, voucher programs, sliding-scale fees, and, increasingly, participation in health insurance schemes have been successfully used alongside social franchising in a number of countries. (See related HIP brief on Vouchers.) Given the higher up-front costs associated with LARCs, voucher programs have successfully increased the proportion of clients opting for a voluntary LARC method at a social franchise facility within the context of informed choice.2,22

- The private medical sector, especially the outpatient sector, has adequate infrastructure and human resource capacity

- Poor and underserved client groups currently seek care from private providers

- The public sector is overburdened and/or unable to adequately address unmet need for family planning

- The government is interested in and supportive of developing, regulating, or contracting the private sector

- Clients or third-party payers are willing to buy health services offered in small or mid-size private-sector outlets

- Clients or third-party payers are able to pay for services, either through out-of-pocket payments, health insurance, or other demand-side financing schemes

- Adequate resources are available for franchise set-up and ongoing management

- The policy environment is favorable to task sharing whereby mid-level providers can offer the franchised package of services

These research questions, reviewed by the HIP technical advisory group, reflect the prioritized gaps in the evidence base specific to the topics reviewed in this brief and focus on the HIP criteria.

- What is the effect of social franchising on contraceptive prevalence in communities served by social franchise clinics?

- What is the differential impact on contraceptive use of social franchising with and without a voucher component?

- What are the associated costs with maintaining a social franchise?

Social Franchising for Health e-learning course uses interactive content and real-life country examples to teach participants about social franchising models. https://www.globalhealthlearning.org/course/social-franchising

Total Market Approach to Family Planning Services e-learning course aims to teach participants about effectively targeting subsidies in health systems where health care is delivered through both the public and private sector. https://www.globalhealthlearning.org/course/total-market-approach-family-planning-services

Clinical Social Franchising Compendium. An Annual Survey of Programs: Findings From 2015 features findings from an annual survey of social franchise programs worldwide, including the geographies and populations they serve, the health care services they franchise, how they work, and how well they work. https://globalhealthsciences.ucsf.edu/sites/globalhealthsciences.ucsf.edu/files/pub/sf4h-social-franchising-compendium-2016.pdf

The Metrics Working Group, comprised of implementing, academic, research, and donor institutions, identifies, tests, and advocates for clear, robust performance metrics to address critical gaps in the social franchising evidence base; it has identified six areas for standardization of metrics and expansion of the evidence base. https://m4mgmt.org/resources/

References

1. About Social Franchises. Social Franchising for Health website. http://sf4health.org/about-social-franchises. Accessed January 29, 2018.

2. Azmat SK, Shaikh BT, Hameed W, et al. Impact of social franchising on contraceptive usewhen complemented by vouchers: a quasi-experimental study in rural Pakistan. PLoS One.2013;8(9):e74260. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074260

3. Duvall S, Thurston S, Weinberger M, Nuccio O, Fuchs-Montgomery N. Scaling up deliveryof contraceptive implants in sub-Saharan Africa: operational experiences of Marie StopesInternational. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2(1):72-92. doi: https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00116

4. Beyeler N, York De La Cruz A, Montagu D. The impact of clinical social franchising on healthservices in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60669.doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060669

5. Berendes S, Heywood P, Oliver S, Garner P. Quality of private and public ambulatory healthcare in low and middle income countries: systematic review of comparative studies. PLoS Med.2011;8(4):e1000433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000433

6. Patouillard E, Goodman CA, Hanson K, Mills A. Can working with the private for-profit sectorimprove utilization of quality health services by the poor? A systematic review of the literature. IntJ Equity Health. 2007;6:17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-6-17

7. Munroe E, Hayes B, Taft J. Private-sector social franchising to accelerate family planningaccess, choice, and quality: results from Marie Stopes International. Glob Health Sci Pract.2015;3(2):195-208. doi: https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00056

8. Huntington D, Mundy G, Mo Hom N, Li Q, Aung T. Physicians in private practice: reasonsfor being a social franchise member. Health Res Policy Syst. 2012;10:25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-10-25

9. Ngo AD, Alden DL, Pham V, Phan H. The impact of social franchising on the use of reproductivehealth and family planning services at public commune health stations in Vietnam. BMC HealthServ Res. 2010;10:54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-54

10. Sieverding M, Briegleb C, Montagu D. User experiences with clinical social franchising: qualitativeinsights from providers and clients in Ghana and Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0709-3

11. Chakraborty NM, Mbondo M, Wanderi J. Evaluating the impact of social franchising on familyplanning use in Kenya. J Health Popul Nutr. 2016;35(1):19. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-016-0056-y

12. Hennink M, Clements S. The impact of franchised family planning clinics in poor urbanareas of Pakistan. Stud Fam Plann. 2005;36(1):33-44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2005.00039.x

13. Keeley R, Vogus A, Mitchell S, Amper MR. Private midwife provision of IUDs: lessons fromthe Philippines. Bethesda, MD: Strengthening Health Outcomes through the Private SectorProject, Abt Associates Inc; 2014. https://www.shopsplusproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/Private%20Midwife%20Provision%20of%20IUDs%20-%20Lessons%20from%20the%20Philippines.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2018.

14. Viswanathan R, Behl R, Seefeld CA. Clinical social franchising compendium. An annual survey ofprograms: findings from 2015. San Francisco, CA: The Global Health Group, Global Health Sciences, University of California, San Francisco. Social Franchising for Health; 2016. http://sf4health.org/sites/sf4health.org/files/sf4h-social-franchisingcompendium-2016.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2018.

15. Tougher S, Dutt V, Pereira S, et al. Effect of a multifaceted social franchising model on quality and coverage of maternal, newborn, and reproductive health-care services in Uttar Pradesh, India: a quasi-experimental study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(2):e211–e221. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30454-0

16. Agha S, Karim AM, Balal A, Sosler S. The impact of a reproductive health franchise on client satisfaction in rural Nepal. Health Policy Plann. 2007;22(5):320-328. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czm025

17. Impact 2: An innovative tool for measuring the impact of reproductive health programmes. Marie Stopes International website. http://mariestopes.org/impact-2. Accessed February 11, 2018.

18. Plautz A, Meekers D, Neukom J. The impact of the Madagascar TOP Réseau social marketing program on sexual behavior and use of reproductive health services. PSI Research Division Working Paper No. 57. Washington, DC: Population Services International (PSI); 2003.

19. Decker M, Montagu D. Reaching youth through franchise clinics: assessment of Kenyan private sector involvement in youth services. J Adol Health. 2007;40:280-282. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.018

20. Shah NM, Wang W, Bishai DM. Comparing private sector family planning services to government and NGO services in Ethiopia and Pakistan: how do social franchises compare across quality, equity and cost? Health Policy Plann. 2011;26:63-71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czr027

21. Bishai D, Sachathep K, LeFevre A, et al; Social Franchising Research Team. Cost-effectiveness of using a social franchise network to increase uptake of oral rehydration salts and zinc for childhood diarrhea in rural Myanmar. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2015;13:3. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-015-0030-3

22. Bellows B, Mackay A, Dingle A, Tuyiragize R, Nnyombi W, Dasgupta A. Increasing contraceptive access for disadvantaged populations with vouchers and social franchising in Uganda. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(3):446-455. doi: https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00065

23. Thurston S, Chakraborty NM, Hayes B, Mackay A, Moon P. Establishing and scaling-up clinical social franchise networks: lessons learned from Marie Stopes International and Population Services International. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(2):180–194. doi: https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00057

Suggested citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Social franchising: Improving quality and expanding contraceptive choice in the private sector. Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development; 2018 February. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/social-franchising

Acknowledgements

This brief was written by Sarah Thurston, Elaine Menotti, and Shawn Malarcher. Critical review and helpful comments were provided by Michal Avni, Joe Bish, Luke Boddam-Whetham, Paata Chikvaidze, Tamar Chitashvili, Megan Christofield, Kimberly Cole, Ramatu Dorada, Hillary Eason, Ellen Eiseman, Gillian Eva, Mario Festin, Sarah Fox, Kate Gray, Anna Gerrard, Denise Harrison, Dana Hovig, Roy Jacobstein, Joan Kraft, Ben Light, Anna Mackay, Baker Maggwa, Ados May, Erin Mielke, Dani Murphy, Alice Payne Merritt, John Pile, Pierre Moon, May Post, Caroline Quijada, Jim Shelton, Martyn Smith, Nandita Thatte, Caitlin Thistle, Caroll Vasquez, and Matthew Wilson.

This brief is endorsed by: Abt Associates, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, CARE, Chemonics International, EngenderHealth, FHI 360, FP2020, Georgetown University/Institute for Reproductive Health, International Planned Parenthood Federation, IntraHealth International, Jhpiego, John Snow, Inc., Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, Marie Stopes International, Options, Palladium, PATH, Pathfinder International, Population Council, Population Reference Bureau, Population Services International, Promundo US, Public Health Institute, Save the Children, U.S. Agency for International Development, United Nations Population Fund, and University Research Co., LLC.

The World Health Organization/Department of Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: http://www.who.int/topic/family_planning/en/.

For more information about HIPs, please contact the HIP team.