Mobile Outreach Services: Expanding access to a full range of modern contraceptives

Background

Mobile outreach services address inequities in access to family planning services and commodities in order to help women and men meet their reproductive health needs. Outreach models allow for flexible and strategic deployment of resources, including health care providers, family planning commodities, supplies, equipment, vehicles, and infrastructure, to areas in greatest need at intervals that most effectively meet demand.

Evidence demonstrates that mobile outreach services can successfully increase contraceptive use, particularly in areas of low contraceptive prevalence, high unmet need for family planning, and limited access to contraceptives, and where geographic, economic, or social barriers limit service uptake. When mobile outreach services are well-designed, they help programs broaden the contraceptive method mix available to clients, including increasing access to long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) and permanent methods (PMs). LARCs and PMs are typically unavailable in most rural or hard-to-reach areas due to lack of skilled providers, commodities, and equipment. Mobile outreach service delivery addresses these access barriers by bringing information, services, contraceptives, and supplies to where women and men live and work, generally free-of-charge or at a subsidized rate. Mobile outreach programs can also leave a lasting legacy that strengthens existing health systems when the model includes developing and supporting local health workers’ knowledge and skills to provide a wider range of methods.

Various models of mobile outreach service delivery have been implemented successfully at large scale. Distinctions between models are based on who is providing the services, where services are being delivered, and what type of arrangement underpins the relationships and shared responsibilities between public and private/nongovernmental sectors. Mobile outreach services are implemented by, or in collaboration with, local public health authorities, strengthening the existing health system and building or strategically deploying local capacity to underserved areas. Mobile outreach services often rely on public-private partnerships, creating an efficient network of private, nongovernmental, and government health care providers that together enable access to comprehensive family planning services.

This brief describes the role of mobile outreach programs as a means of reducing inequities in access to family planning services (particularly LARCs and PMs), discusses the potential contribution of these programs, and outlines key issues for planning and implementation. Mobile outreach services is one of several proven “high-impact practices in family planning” (HIPs) identified by a technical advisory group of international experts. When scaled up and institutionalized, HIPs will maximize investments in a comprehensive family planning strategy (HIPs, 2013). For more information about HIPs, see www.fphighimpactpractices.org/overview.

Which challenges can this practice help countries address?

- Mobile outreach services serve communities with limited access to clinical providers and supplies. Geographic distribution of human resources for health, along with availability of medical commodities and supplies, determines which health services will be available as well as the quantity and quality of such services. Populations residing in rural areas, urban slums, and marginalized communities experience either geographic or economic barriers to qualified health workers, which contribute to large inequities in health outcomes and use of health services. The World Health Report 2006 identified 57 countries facing critical shortages in health personnel (WHO, 2006). In addition to deploying trained clinical providers, mobile outreach service delivery models ensure a reliable supply of contraceptive commodities, medical supplies, and equipment needed to deliver a full range of family planning options.

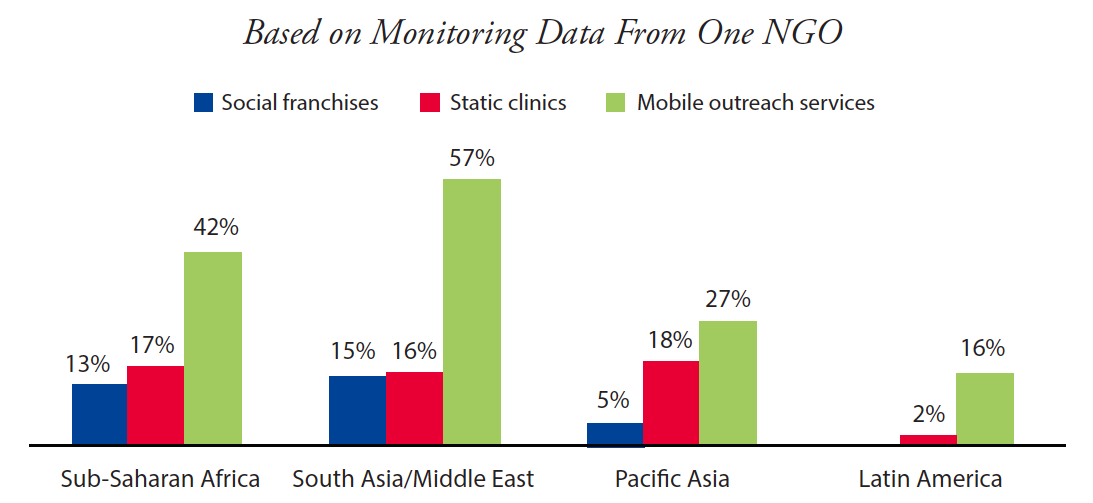

- Mobile outreach services reach new and underserved populations by bringing health services closer to the client. Mobile outreach service clients are likely to be new to family planning—this is the case for 41% of mobile outreach clients in sub-Saharan Africa, 36% in South Asia and the Middle East, 47% in Pacific Asia, and 23% in Latin America (Hayes et al., 2013). Along with other service delivery channels, mobile outreach offers an effective way to also reach the poor. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa in 2012, 42% of mobile outreach clients of one international nongovernmental organization (NGO) lived on less than US$1.25 per day, compared with 17% and 13% of clients of static clinics and social franchises, respectively (Figure 1).

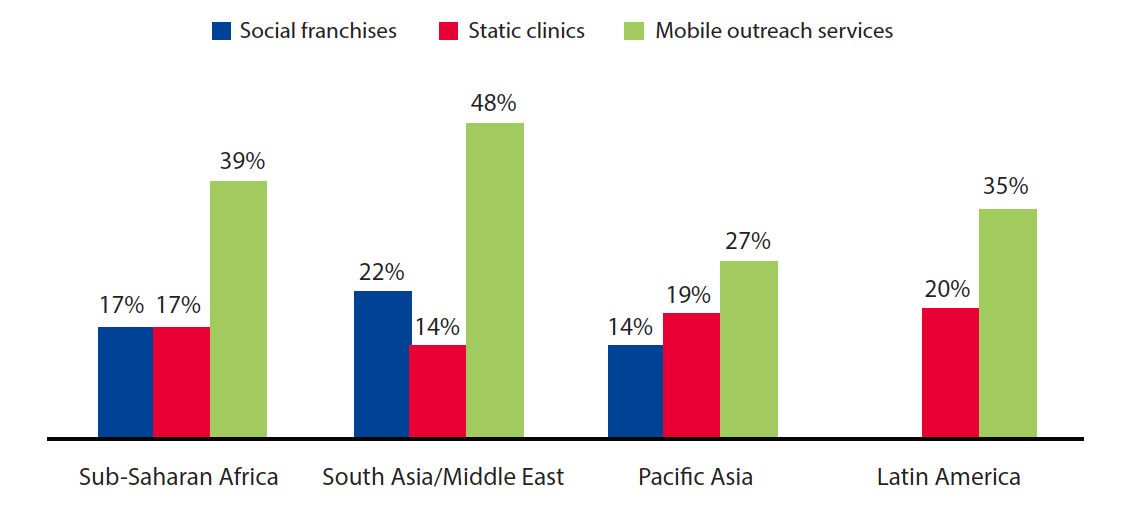

- Mobile outreach services expand method choice. The methods delivered through mobile outreach supplement widely available methods, including short-acting methods. Specifically, mobile outreach services enable access to LARCs and PMs, which are less accessible in many developing-country health systems. While nearly one-quarter of women in developed countries rely on LARCs and PMs to avoid unintended pregnancy, less than 5% of women in the least developed countries use these methods (United Nations, 2011). In 2010, over half of all LARCs and PMs in Tanzania were provided through mobile outreach (Jones, 2011). In Nepal, government-run mobile clinics provide 20% of voluntary female sterilization procedures and over one-third of voluntary male sterilization procedures (MOHP [Nepal] et al., 2012). Service statistics from one international NGO indicate that mobile outreach services may increase opportunities for family planning clients to switch to LARCs or PMs to meet their stated reproductive intentions (Figure 2).

- Mobile outreach supports capacity building of providers to deliver LARCs and PMs. Regular visits by mobile outreach service providers to under-resourced health facilities offer opportunities for on-the-job training and reinforcement of clinical and counseling skills, infection prevention measures, and management of client flow. Experience from India demonstrates that in areas where use of LARCs and PMs is low, programs can develop and maintain provider skills more efficiently by training a smaller number of mobile providers who serve a large catchment area through different delivery points rather than training a large number of providers who serve a small number of clients (Bakamjian, 2008).

What is the impact?

Mobile outreach can increase contraceptive use. Evidence from a recent evidence review suggests that outreach and community-based distribution are “effective and acceptable ways of increasing access to contraceptives, particularly injectables and long-acting and permanent methods” (Mulligan et al., 2010). When implemented at scale, and with attention to providing high-quality services, communities served by mobile outreach services increase use of modern contraceptives.

- A study in Zimbabwe concluded that mobile outreach services “have a powerful effect” on use of contraceptives. After controlling for social and economic characteristics, researchers found that exposure to mobile outreach services had the same magnitude of effect on current and ever contraceptive use as having a general hospital in the area. The study also found that mobile family planning units had their greatest impact among the poor as they seem to serve women with little education (Thomas and Maluccio, 1996).

- Mobile outreach services have played a critical role in contraceptive provision in Nepal. In 2011, 13% of all modern method users obtained their method from government mobile clinics, including nearly 20% of all female sterilization users and approximately one-third of male sterilization users (MOHP [Nepal] et al., 2012).

- Between 2004 and 2010, Malawi experienced a 14 percentage point increase in modern contraceptive prevalence among married women—from 28% to 42% (NSO [Malawi] and ICF Macro, 2011). A case study of Malawi’s experience concluded that the mobile outreach service delivery program played a key role in achieving this success (USAID/Africa Bureau et al., 2012).

- Introduction of mobile services within existing clinic-based services in a post-conflict setting in Northern Uganda led to increased use of modern contraception, from 7% in 2007 to 23% in 2010, including increased use of LARCs and PMs, from 1% to 10% (Casey, 2013).

- Tanzania experienced a slight but steady increase in modern contraceptive use between 2004/05 and 2010—from 20% to 27% (NBS [Tanzania] and ICF Macro, 2011). According to interviews with key officials, mobile outreach contributed to this increase, although the magnitude of effect is unknown (Wickstrom et al., 2013).

Cost-effectiveness should be evaluated while designing a mobile outreach program. The cost of delivering family planning services through mobile outreach varies by the model used; the number and cadre of providers employed; and the distance that mobile outreach teams must travel and the associated transportation costs. A prospective economic analysis of service delivery in Ethiopia comparing the cost-effectiveness of outreach by clinical specialists with provision of the same services through a referral system found that outreach was 1.45 times more cost-effective in using scarce clinical specialists’ time than the referral system (Kifle and Nigatu, 2010). In Tunisia, a study concluded that although one-fourth of the national family planning operating budget supported the mobile outreach program, the mobile units contributed one-third of the total output of the national program. More importantly, the mobile units contributed an even greater share of the national program’s activities in rural areas and played a critical role in expanding the geographic coverage of family planning services (Coeytaux et al., 1989). It is important to note that cost-efficiencies may not translate to other health services and that there is little information on long-term financial sustainability.

Mobile outreach services can provide high-quality care. A study in Nepal concluded that female sterilization services provided through mobile outreach and in hospitals were comparable in terms of client screening and quality of care (Thapa and Friedman, 1998). Observational studies in India found that incidence of side effects and complications for clients receiving IUDs or sterilization services through mobile services were similar to rates in published literature (Aruldas et al., 2013).

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

The table below describes the range of models used for mobile outreach service delivery. The “classic” model uses a team of clinical providers that travels to communities in a mobile clinic or that sets up a clinic in temporary settings, representing the most resource-intensive model. On the other hand, the “dedicated provider” model involves a single provider who focuses on providing contraceptives, particularly LARCs and/ or PMs, and is embedded in an existing health facility. This model is usually less resource-intensive than other models.

Various Models of Mobile Outreach Service Delivery

| More Resource-Intensive ←→ Less Resource-Intensive | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Classic | Streamlined | Dedicated Provider | |

| Who? |

|

|

A single provider (medical doctor, assistant medical clinical officer, nurse, or nurse-midwife). |

| What? | LARCs and PMs, in addition to short-acting methods. |

|

LARCs (and possibly PMs). |

| Where? | Existing health facilities, schools, community buildings, tents, or mobile van. | Existing health facilities, schools, or community buildings, or, in unique settings with limited mobility of women, a client’s home. | Seconded to one or more health facilities. |

| Arrangement | NGO-led and staffed, or NGO-coordinated and public sector-staffed. | NGO-led and staffed, or NGO-coordinated and public sector-staffed. | Providers may be attached to or employed by the facility, such as a district hospital, but are mobile to offer services at lower-level facilities or in clients’ homes. |

| Potential Application |

|

|

|

| Special Considerations |

|

|

|

- Coordinate with community leaders to identify appropriate locations. Distance from a service provider is not always the primary barrier for clients with unmet need for family planning. Barriers may also include inability to pay for transport or lack of contraceptive choice at a nearby facility. Consequently, mobile outreach services can be successfully deployed to address unmet need in rural as well as urban areas. Coordination with local government well in advance of outreach visits helps ensure that selected sites have appropriate space and that site staff are committed to accommodating space and other needs of the mobile team.

- Map the geographic area. Mapping the location of focus communities within an outreach catchment area will enable service providers to identify appropriate outreach sites and effectively plan and schedule the mobile team’s visit. In Somalia, use of a geographic information system (GIS) map helped with the logistical planning and delivery of mobile outreach services by directing the ambulance and nurses safely to refugee camps in an area marred with long and prolonged natural and human disasters (Shaikh, 2008). (For more information about new technologies, see the Digital Health HIP brief at www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/digital-health-systems.)

- Ensure that sites are clean, safe, and private. Any site used for mobile outreach services needs to be safe and clean, and it needs to provide space for privacy during counseling, the procedure, and recovery. Adequate space can be a significant barrier for effective outreach service delivery.

- Develop effective public-private partnerships. Mobile outreach service arrangements allow Ministries of Health and NGOs to work together in order to expand the reach of both partners to meet national health goals. These partnerships facilitate a holistic approach by filling gaps where services are lacking or providing technical assistance where services are limited. Although mobile outreach often has been seen as a stop-gap measure while building the capacity of under-resourced health systems, an increasing number of countries are experimenting with contracting relationships that position mobile outreach as an integral part of the health system. Formal contracting allows governments to commission mobile outreach services that are delivered, in part or fully, by private/NGO providers in collaboration with the public sector. These relationships leverage the clinical skills and geographic flexibility of private/NGO providers while allowing Ministries of Health to guide priority setting and allocation of resources.

- Work with CHWs to assist with follow up and to refer complications to higher levels of service.

- Use mobile phones and SMS for follow-up messaging.

- Use hotlines for information about follow-up care.

- Ensure mobile outreach teams are equipped to offer LARC removals, and ensure a strong referral network is in place to guarantee access to removals between visits.

- Recruit and support dedicated staff. Recruiting and retaining trained mobile outreach providers—either from the government or through NGOs—is critical to the success of any mobile outreach program. Staff may be engaged on a part-time or full-time basis or may offer outreach services as part of their regular jobs. Travel demands and time away from family and community can be challenging, especially with the classic mobile outreach model that reaches rural areas. Thus, mobile outreach programs often struggle with staff retention. Staff work plans and schedule rotations should be reviewed regularly, and travel dates should be set in advance so that the arrival of the mobile team is predictable for both clients and providers.

- Invest in sustained awareness-raising and communication activities. Clients in underserved communities often lack knowledge about family planning and have limited exposure to media and communication channels (Mwaikambo, 2011). Low population density in rural areas makes effective communication more challenging. Clients in peri-urban and urban areas, while more exposed to media than their rural counterparts, may still face information barriers stemming from poor educational opportunities and limited access to health information. Therefore, sustained awareness-raising through community channels is critical to the success of investments in mobile outreach service delivery. Clients of mobile outreach services frequently report that they first heard of the program either through word-of-mouth (friends, relatives, and satisfied clients), community health workers (CHWs), loudspeakers, radio, and community events (Eva and Ngo, 2010). (For more information about communication, see the Health Communication HIP brief at www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/health-communication.)

- Link outreach programs with CHWs and local clinics for family planning counseling, referrals, and community mobilization. CHWs typically live in the community they serve and are generally selected by the communities in which they operate. As a result, CHWs often have strong local networks and knowledge. Mobile outreach programs often engage CHWs to communicate the location and dates of mobile outreach service days. In addition, CHWs conduct demand generation, education activities, and basic family planning counseling a few days prior to the visit of the mobile outreach team. This helps to secure buy-in and to generate interest within the community prior to the delivery of services, offers an opportunity for direct referrals for services, and links to the nearest clinic in case of adverse events or need for method removal.

- Anticipate and address challenges. Potential challenges range from transportation difficulties and logistics issues to client misinformation about family planning and ensuring follow-up care. Anticipating these challenges in advance and making plans for how to address them if they arise will help ensure mobile outreach programs are successful.

Expanding Contraceptive Choice to the Underserved Through Delivery of Mobile Outreach Services: A Handbook for Program Planners provides general guidance on how to design and implement mobile outreach family planning services and should be adapted to each country’s context. This handbook includes two tools as appendices: (1) minimum guidelines for managing an outreach program, and (2) a sample partner agreement. Available from: https://toolkits.knowledgesuccess.org/toolkits/communitybasedfp/expanding-contraceptive-choice-underserved-through-delivery-mobile

For more information about High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs), please contact the HIP team.

References

Aruldas K, Khan ME, Ahmad J, Dixit A. Increasing choice and access to family planning services via outreach in Rajasthan, India: an evaluation of MSI India’s outreach services. New Delhi: Population Council; 2013.

Bakamjian L. Linking communities to family planning and LAPM via mobile services. Presented at: Flexible Fund Partner’s Meeting; 2008; Washington, DC.

Casey S, McNab S, Tanton C, Odong J, Testa A, Lee-Jones L. Availability of long-acting and permanent family-planning methods leads to increase in use in conflict-affected northern Uganda: evidence from cross-sectional baseline and endline cluster surveys. Global Public Health 2013;8(3):284-297. Available

from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2012.758302

Coeytaux F, Donaldson D, Aloui T, Kilani T, Fourati H. An evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of mobile family planning services in Tunisia. Studies in Family Planning 1989;20(3):158-169.

Eva G, Ngo TD. MSI mobile outreach services: retrospective evaluations from Ethiopia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sierra Leone and Viet Nam. London: Marie Stopes International; 2010. Available from: https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/outreach_web.pdf

Hayes G, Fry K, Weinberger M. Global impact report 2012: reaching the under-served. London: Marie Stopes International; 2013. Available from: http://www.mariestopes.org/sites/default/files/Global-Impact-Report-2012-Reaching-the-Under-served.pdf

High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). High-impact practices in family planning list. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development; 2013. Available from: http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/high-impact-practices-in-family-planning-list

Jones B. Mobile outreach services: multi-country study and findings from Tanzania. New York: The RESPOND Project/EngenderHealth; 2011. Available from: http://www.respond-project.org/pages/files/5_in_action/lapm-cop-mobile-services/Barbara-Jones.pdf

Kifle Y, Nigatu T. Cost-effectiveness analysis of clinical specialist outreach as compared to referral system in Ethiopia: an economic evaluation. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 2010;8:13. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-7547-8-13

Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) [Nepal]; New ERA; ICF International Inc. Nepal demographic and health survey 2011. Kathmandu, Nepal: MOHP; 2012. Co-published by ICF International. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR257/FR257[13April2012].pdf

Mulligan J, Nahmias P, Chapman K, Patterson A, Burns M, Harvey M, et al. Improving reproductive, maternal and newborn health: reducing unintended pregnancies. Evidence overview. A working paper (version 1.0). London: Department for International Development (DFID); 2010. Available from: http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/Output/185828/Default.aspx

Mwaikambo L, Speizer IS, Schurmann A, Morgan G, Fikree F. What works in family interventions: a systematic review. Studies in Family Planning 2011; 42(2):67-84. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3761067/

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) [Tanzania]; ICF Macro. Tanzania demographic and health Survey 2010. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: NBS; 2011. Co-published by ICF Macro. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR243/FR243[24June2011].pdf

National Statistical Office (NSO) [Malawi]; ICF Macro. Malawi demographic and health survey 2010. Zomba, Malawi: NSO; 2011. Co-published by ICF Macro. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR247/FR247.pdf

Shaikh MA. Nurses’ use of global information systems for provision of outreach reproductive health services to internally displaced persons. Prehosp Disaster Med 2008;23(3):s35-8.

Thapa S, Friedman M. Female sterilization in Nepal: a comparison of two types of service delivery. Int Fam Plann Perspect 1998;24(2):78–83. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/2407898.pdf

Thomas D, Maluccio J. Fertility, contraceptive choice, and public policy in Zimbabwe. The World Bank Economic Review 1996;10(1):189-222. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/860011468336005200/pdf/771130JRN0WBER0Box0377291B00PUBLIC0.pdf

United Nations (UN), Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World contraceptive use 2011. New York: UN; 2011. Available from: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/contraceptive2011/contraceptive2011.htm

USAID/Africa Bureau; USAID/Population and Reproductive Health; Ethiopia Federal Ministry of Health; Malawi Ministry of Health; Rwanda Ministry of Health. Three successful Sub-Saharan Africa family planning programs: lessons for meeting the MDGs. Washington, DC: USAID; 2012. Available from: http://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/africa-bureau-case-study-report.pdf

Wickstrom J, Yanulis J, Van Lith L, Jones B. Approaches to mobile outreach services for family planning: a descriptive inquiry in Malawi, Nepal, and Tanzania. The RESPOND Project Study Series: Contributions to Global Knowledge, Report No. 13. New York: The RESPOND Project, EngenderHealth; 2013. Available from: http://www.respond-project.org/pages/files/6_pubs/research-reports/Study13-Mobile-Services-LAPM-September2013-FINAL.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO). The World Health Report 2006: working together for health. Geneva: WHO; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/

Suggested Citation

High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Mobile outreach services: expanding access to a full range of modern contraceptives. Washington, DC: USAID; 2014 May. Available from: http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/mobile-outreach-services

Acknowledgements

This document was originally drafted by Julie Solo and Shawn Malarcher. Critical review and helpful comments were provided by Ian Askew, Lynn Bakamjian, Regina Benevides, Salwa Bitar, Christine Bixiones, Linda Casey, Maxine Ebers, Fariyal Fikree, Nomi Fuchs-Montgomery, Leah Sawalha Freij, Jennifer Friedman, Gwyn Hainsworth, James Harcourt, Trish MacDonald, Stembile Mugore, Hashina Begum, Mohammad Murtala Mai, Nithya Mani, Ilka Rondinelli, Jeff Spieler, Sarah Thurston, Jane Wickstrom, and John Yanulis.

This HIP brief is endorsed by: Abt Associates, Chemonics, EngenderHealth, FHI 360, Futures Group, Gates Foundation, Georgetown University’s Institute for Reproductive Health, International Planned Parenthood Federation, IntraHealth International, Jhpiego, John Snow, Inc., Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Communication Programs, Marie Stopes International, Pathfinder International, Plan International USA, Population Council, Population Reference Bureau, Population Services International, United Nations Population Fund, and the United States Agency for International Development.

The World Health Organization/Department of Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of this document, which is viewed as a summary of evidence and field experience. It is intended that this brief be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: http://www.who.int/topics/family_planning/en/.