Immediate Postpartum Family Planning: A key component of childbirth care

Background

Offering modern contraception services as part of care provided during childbirth increases postpartum contraceptive use and is likely to reduce both unintended pregnancies and pregnancies that are too closely spaced.1,2 Unintended and closely spaced births are a public health concern as they are associated with increased maternal, newborn, and child morbidity and mortality.3-8 After a live birth, the recommended interval before attempting the next pregnancy is at least 24 months, based on a consultation convened by the World Health Organization (WHO), in order to reduce the risk of adverse maternal, perinatal, and infant outcomes.9 Despite this evidence, 61% of postpartum women in low- and middle-income countries have an unmet need for contraception.10

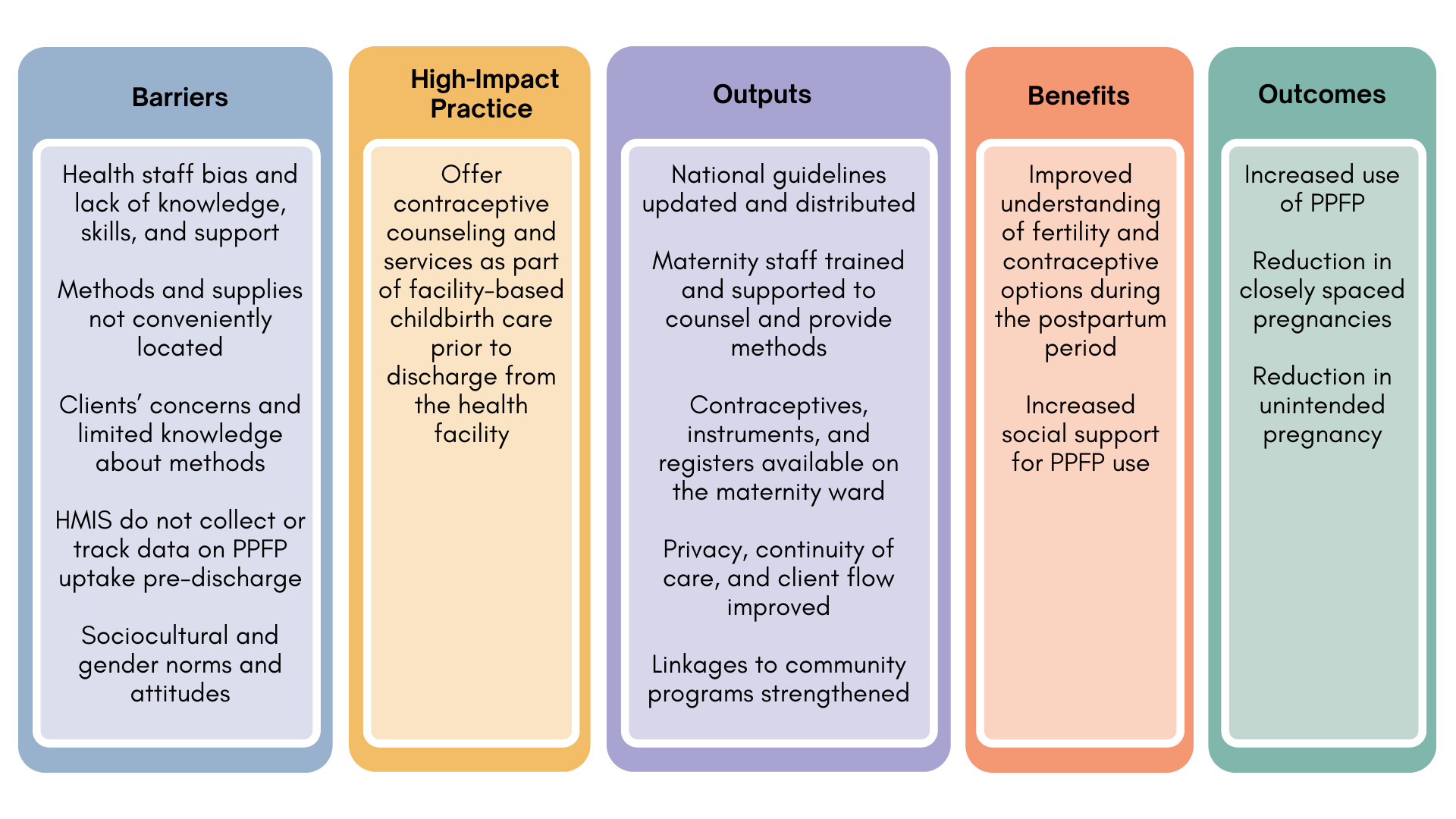

There are many reasons why women do not use effective contraception during the postpartum period, such as sociocultural and gender norms that guide postnatal practices,11,12 timing of return to menses13,14 and sexual activity,12 breastfeeding practices and misconceptions of conditions for lactational amenorrhea,11,15 and lack of access to contraceptive services (Figure 1). The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted access to essential health services, including access to facility-based birth and immediate postpartum family planning care. A WHO survey found 68% of countries surveyed reported disruption to family planning services and 32% reported disruption to facility birth service,16 though these estimates were not specific to postpartum services.

This High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP) brief summarizes the evidence and provides implementation tips for proactively offering family planning as part of care during and immediately after childbirth, often referred to as the immediate postpartum period. (Offering services during the postpartum period is a common approach to addressing gaps in access to services; see, for example, the Family Planning and Immunization Integration HIP brief.)

The WHO recommends that women receive information on family planning and the health and social benefits of birth spacing during antenatal care, immediately after birth, and during postpartum and well-baby care, including immunization and growth monitoring.17 Each visit to a health professional offers a unique opportunity to screen for, counsel, and offer family planning services. Yet each opportunity requires deliberate attention to organize services, update policies and provider practices, and mobilize resources for successful implementation. Facility-based childbirth services offer an ideal platform to reach women and their partners with family planning information and services, provided women’s right to make a full and informed choice are respected. Immediate postpartum family planning is one of several proven HIPs identified by a technical advisory group of international experts. A proven practice has sufficient evidence to recommend widespread implementation as part of a comprehensive family planning strategy, provided that there is monitoring of coverage, quality, and cost as well as implementation research to strengthen impact.18 For more information about other HIPs, see http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/overview.

Why is this practice important?

Providing family planning counseling as part of childbirth care raises awareness of the importance of birth spacing and postpartum contraceptive options. Women and their partners often have limited understanding about contraceptive options, return to fertility, and risks of a closely spaced or unintended pregnancy soon after childbirth.11,12,19 Providers, women, and their support networks cite concerns about contraceptive side effects, especially related to effects of hormonal contraceptives on breast milk and the child’s health as reasons to avoid contraception during the postpartum period.10,20,21 In settings where women seek care well before active labor or in communities where women are able to recuperate in a facility after birth, family planning counseling can be incorporated into care around the preparation for childbirth and/or immediately thereafter; these approaches are considered acceptable to both providers and clients. Providing information at this time can improve knowledge and attitudes regarding the use of postpartum contraception.22-26

An increasing number of women and their partners can be reached through facility-based childbirth services. Globally, 4 of 5 births take place with the assistance of a skilled birth attendant, and increasingly these births are taking place in health facilities.27 For example, in Bangladesh, deliveries in health facilities increased from 17% to 37% between 2007 and 2014. During a similar time frame, facility deliveries increased from 39% to 72% in Burkina Faso and from 43% to 64% in Kenya.28 As countries continue to strengthen facility-based childbirth care, this will be an increasingly important platform to reach women and their partners with family planning services.

Women have more contraceptive options during the immediate postpartum period. Based on a consultation convened by WHO, women can safely use contraceptive implants during the immediate postpartum period,29 in addition to many other types of contraceptives (see Box 01). Therefore, immediately after birth, women may choose from a wide variety of contraceptives including hormonal and non-hormonal, long- and short-acting, and permanent methods.30

For breastfeeding women:

- Female sterilization

- Male sterilization

- Intrauterine device (IUD)

- Implants

- Progestogen-only pills

- Lactational amenorrhea method (LAM)

- Condoms

For non-breastfeeding women*:

- Female sterilization

- Male sterilization

- IUD

- Implants

- Injectables

- Condoms

- Emergency contraception

*Promote advance provision of Combined Oral Contraceptives while women are in the facility with counseling to begin after 21 days.

Source: WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (2015).29

What is the impact?

Offering modern contraception as part of childbirth services increases postpartum contraceptive use. Immediate postpartum family planning is not a new concept. The International Postpartum Program, implemented from 1966 to 1973 in 138 institutions across 21 countries and reaching 3.5 million women, demonstrated the feasibility of providing family planning services in the context of hospital-based obstetric care. In 1971, at the height of implementation, approximately 21% of obstetric patients in participating facilities obtained contraception during the immediate postpartum period, proving that family planning services could be incorporated into obstetric wards quickly and at low cost.31 The program is estimated to have averted 500,000 unwanted pregnancies over its 8 years of implementation.31

More recent experiences consistently demonstrate the potential impact of this practice. Between 2013 and 2017, the International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians conducted a large multi-country collaboration with ministries of health to strengthen immediate postpartum family planning, including counseling, training, monitoring, and service delivery.32 One component was revitalizing voluntary postpartum IUDs (PPIUD) as a method for immediate postpartum family planning. In four countries—India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania—6,477 doctors, nurses, and midwives were trained, serving 239,033 women delivering between January 2016 and November 2017; 68% received balanced counseling on family planning and 20% chose an IUD.33 Multiple counseling sessions during the course of a pregnancy contributed to higher postpartum family planning uptake. In Sri Lanka, a pilot introduction of PPIUD in 12 major hospitals over several years led to PPIUDs being included as a method in the national family planning program in 2017.34

Training nurses and midwives in immediate PPIUD insertion was particularly successful, achieving increased PPIUD uptake with few complications, expulsions, and removals. In a major Indian hospital, PPIUD uptake increased from 2.3% to 49.0% over 2 years with 99.5% of 2,626 vaginal insertions performed by trained nurses.35 In Tanzania, midwives performed 58.5% of 2,347 PPIUD insertions.36 Overall lessons for success included emphasis on country-level and hospital-based leadership, on-the-job training, competency standards, prenatal counseling, and robust monitoring, evaluation, and feedback.32,37,38

Table 1 summarizes experience from 6 country programs, 3 of which (Afghanistan, Indonesia, and Niger) are based on unpublished data. The time frame examined in all the studies was the immediate postpartum period prior to women leaving the facility. Studies were considered if multiple contraceptive methods were offered. Taken together, old and new, these findings show that if women are provided comprehensive counseling and are proactively offered contraception from a range of choices as part of childbirth care, between 20% and 50% of women will leave the facility with a method. This is consistent with other evidence that found women were significantly more likely to be using modern contraception postpartum if they were offered family planning services at the time of delivery.39-41

Percentage of Women Giving Birth Leaving the Facility With a Modern Contraceptive Method, Before and After Introduction of Contraceptive Counseling and Services During Childbirth Care

| Country | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan42,43 | 4% (180/4179) | 51% (1700/3362) |

| Honduras44* | 10% (47/474) | 33% (188/571) |

| Honduras45† | 9% (23/251) | 46% (142/308) |

| Indonesia46 | 9% (307/3373) | 41% (1286/3101) |

| Niger47,48 | 0% (7/2193) | 31% (686/2213) |

| Rwanda49 | 7.7 PPIUD/month | 214.6 PPIUD/month |

* Hospital Escuela, the government-run hospital.

† Hospital Materno-Infantil in Tegucigalpa, the Honduran Social Security System.

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

Invest in good documentation and monitoring to help ensure voluntarism and informed choice. Childbirth can be a stressful and challenging time for women. Clear documentation and recordkeeping, along with consistent monitoring, can help programs assess progress while ensuring clients’ rights are protected. For example, when counseling is provided during antenatal care, method choice should be indicated on the client’s record, whether it be a woman-held card or a facility chart. This documentation facilitates communication across providers who are caring for the same client and ensures continuity of care. The record should emphasize method choice or refusal, rather than whether or not counseling was provided.

Update national service delivery guidelines and clarify the role of service providers. This is particularly critical if existing guidelines reflect delayed start of progestin- only methods, like implants, which are now an option for immediate postpartum family planning use.29 Guidelines as well as job descriptions should clearly articulate that all antenatal and maternity care providers have a role in postpartum family planning, and that it is not just the responsibility of a few trained provider(s). The role of community health workers in promoting postpartum family planning can also be specified.

Include humanitarian crisis settings. Humanitarian crises are enormous and ever-growing, and the sexual and reproductive health needs of women and adolescent girls experiencing them are often greater than in stable settings.50 With clinical training, community outreach, and a wide range of contraceptive options, programs document rapid increases of immediate postpartum family planning uptake, including long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs). When offering implants and IUDs with balanced counseling and competent services, these methods quickly achieve popularity in unstable settings where women and families may be uprooted at a moment’s notice.51,52

Conduct formative assessments to guide social and behavior change strategies. Understanding barriers to PPFP uptake and tailoring programmatic approaches to address those barriers can improve uptake.53,54 Programs have found that when first starting PPFP services, providers can identify interested clients through counseling during antenatal care services and at birth. As services become established, and programs seek to increase uptake on a sustained basis, demand creation at the community level is needed.55 This is particularly helpful in contexts where misinformation and resistance to IUDs or LARCs is strong in the community in general.55

Consider home visits if targeting postpartum family planning adoption among first-time, young parents. Programs targeting young married women and adolescents have found value in using home visits or community group engagement.56 (See the HIP brief on Community Group Engagement.) Mothers-in-law, co-wives, and other senior women are key influencers of married adolescents. These programs documented the need to carefully test strategies for approaching and counseling young married women, as well as their partners and senior women in the household.57-59

Offer the broadest range of contraceptive methods possible and make them available prior to maternity discharge. Institutions that demonstrate marked improvements in postpartum contraceptive uptake did so by expanding the method mix and by focusing on method adoption during the pre-discharge period. For example, in Honduras, the range of methods available was expanded from IUDs and female sterilization to include progestin-only oral contraceptives and condoms. The result was a fivefold increase in the percentage of postpartum women leaving the hospital with a method of their choice, from 9% in December 1990 to 47% in February 1992.45 A study in Egypt found that counseling on and advance provision of emergency contraceptive pills for LAM users in the event of a delay in transitioning from LAM to another method significantly decreased the incidence of unintended pregnancy and increased timely transition to another method.60

Consider leveraging antenatal care visits to educate clients on contraception. While the effect of including family planning counseling as part of antenatal care on increased postpartum family planning uptake is unclear, doing so may allow women to fully explore their intentions and to make an informed decision about contraception before delivery.61 Counseling earlier during a pregnancy may be particularly helpful if introducing IUD or sterilization, as women often need more time to consider and discuss these options with their partners.

Engage men. In many cultures male partners exert considerable influence on uptake and continuation of immediate postpartum family planning.62-64 Men’s involvement during and after pregnancy can reduce the occurrence of postpartum depression and improve use of maternal health services, such as skilled birth attendance and postnatal care.65

Using couples’ counseling—with women’s concurrence— during antenatal visits at a Northern Nigeria hospital increased immediate postpartum family planning uptake from 29% to 49%.66 A pilot mHealth interactive short messaging service for women and men was well received by both and confirmed men’s desire for inclusion in family planning programs. Utilizing mHealth messaging is a promising approach to enhance couples’ communication and to address men’s and women’s contraceptive knowledge gaps, anticipated side effects, and misconceptions.67 Inequitable gender norms have a powerful effect on women’s ability to make and act on decisions about birth spacing and limiting. Providing men and women the opportunity to engage in family planning discussions as part of maternity care—together or separately—can directly address these inequitable norms and create space for joint decision making for effective use of family planning.

Plan for contraceptive uptake later during the postpartum period. In Rwanda, the postpartum family planning counseling session is an opportunity to make a plan for returning to a facility for postnatal care and immunization and for obtaining a postpartum family planning method at that time. Data from one quarter in 2017 from 10 districts showed that 24% of women adopted a method pre-discharge and an additional 67% left with a plan of when to start (data unpublished). Immunization services tend to reach high coverage and provide a possible platform for linking or integrating family planning services (see related HIP brief on Family Planning and Immunization Integration).

Ensure adequate staff, equipment, and supplies, and if possible ensure their availability 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Needs vary considerably from country to country and from facility to facility, depending on the existing clinic space, the extent to which current staff can undertake this additional responsibility, and the availability of equipment and supplies. Ensuring systematic postpartum family planning counseling may entail making postpartum family planning– trained providers available on call at night or on weekends.45,46,68-70 In addition, conducting whole-site orientations helps ensure that even staff who have not been trained or do not possess a clinical background can support postpartum family planning.55 Make sure to pre- position supplies and organize client flow through labor, delivery, and postnatal wards to identify appropriate space for counseling. In Niger, when the schedule was revised to offer postpartum family planning services at all times rather than during the morning only, the number of women delivering who left with their method of choice increased from 44% to 55% within one month in one rural district hospital (unpublished data).47,48

Encourage facility leadership and adjust management practices based on facility size. Larger facilities may require more intensive engagement of staff than smaller facilities to achieve similar output. In the International Postpartum Family Planning Program, small facilities with motivated providers demonstrated the highest rate of postpartum contraceptive uptake. Among facilities with fewer than 10,000 patients per year, about 27% of obstetric patients opted for contraception during the immediate postpartum period. Facilities with 10,000 to 20,000 patients, however, averaged 17% postpartum contraceptive uptake, and the largest institutions (with caseloads of 20,000 or more) averaged only 13%.71 These findings are consistent with research in Guatemala that found higher rates of postpartum contraceptive uptake at lower levels of the health system.71 Problem-solving strategies, as part of leadership, management, or quality improvement approaches, help staff address barriers as they arise.47,48,72

Implementation measurement

It is recommended that programs implementing postpartum family planning include the following indicators.

- Number/percent of women who delivered in a facility and received counseling on family planning prior to discharge (disaggregated by age group, <20 years vs. ≥20 years). See MEASURE Evaluation FP/RH Indicators Database.

- Number/percent of women who deliver in a facility and initiate or leave with a modern contraceptive method prior to discharge (disaggregated by type of method and age group, <20 years vs. ≥20 years). See MEASURE Evaluation FP/RH Indicators Database.

Compendium of WHO Recommendations for Postpartum Family Planning73 is a web-based tool that integrates core WHO guidance to guide women through their family planning decision-making during the first year postpartum.

Postpartum Family Planning (PPFP) Toolkit74 provides a comprehensive collection of best practices and

evidence-based tools and documents on postpartum family planning.

Programming Strategies for Postpartum Family Planning18 is a resource for program planners and managers when designing interventions to integrate PPFP into national and subnational strategies.

Service Communication Case Study: Bangladesh: Behavioral Maintenance and Follow-Up75 is an example of a project that has successfully used social and behavior change communication via mHealth to communicate important information about pregnancy and the first year of a child’s life, including PPFP, to expecting and new mothers and their families.

References

- Baqui AH, Ahmed S, Begum N, et al. Impact of integrating a postpartum family planning program into a community-based maternal and newborn health program on birth spacing and preterm birth in rural J Glob Health. 2018;8(2):020406. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.08.020406

- Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, Glasier A, Innis Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1810-1827. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(06)69480-4

- Kozuki N, Walker N. Exploring the association between short/long preceding birth intervals and child mortality: using reference birth interval children of the same mother as comparison. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(3):S6. https://doi. org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S6

- Rutstein Effects of preceding birth intervals on neonatal, infant and under-five years mortality and nutritional status in developing countries: evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys. Int J Gyn Obstet. 2005;89:S7-S24. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.012

- Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermúdez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. 2006;295(15):1809-1823. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.15.1809

- DaVanzo J, Hale L, Razzaque A, Rahman The effects of pregnancy spacing on infant and child mortality in Matlab, Bangladesh: how they vary by the type of pregnancy outcome that began the interval. Popul Stud (Camb). 2008;62(2):131-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720802022089

- Conde-Agudelo A, Belizán Maternal morbidity and mortality associated with interpregnancy interval: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2000;321(7271):1255-1259. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7271.1255

- Sully EA, Biddlecom A, Darroch JE, et al. Adding It Up: Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health Guttmacher Institute; 2020. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/adding-it-up-investing-in-sexual-reproductive- health-2019

- World Health Organization (WHO). Report of a WHO Technical Consultation on Birth WHO; 2007. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://apps.who.int/ iris/handle/10665/69855

- Chebet JJ, McMahon SA, Greenspan JA, et al. “Every method seems to have its problems”- Perspectives on side effects of hormonal contraceptives in Morogoro Region, BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:97. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12905-015-0255-5

- Kouyate LAM and the Transition Barrier Analysis: Sylhet, Bangladesh. Jhpiego; 2010.

- Rossier C, Hellen Traditional birthspacing practices and uptake of family planning during the postpartum period in Ouagadougou: qualitative results. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;40(2):87-94. https://doi.org/10.1363/4008714

- Borda MR, Winfrey W, McKaig Return to sexual activity and modern family planning use in the extended postpartum period: an analysis of findings from seventeen countries. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14(4).

- Gahungu J, Vahdaninia M, Regmi PR. The unmet needs for modern family planning methods among postpartum women in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of the literature. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01089-9

- Tran NT, Yameogo WME, Gaffield ME, et al. Postpartum family-planning barriers and catalysts in Burkina Faso and the Democratic Republic of Congo: a multiperspective study. Open Access J Contracept. 2018;9:63-74. https://doi.org/10.2147/ OAJC.S170150

- World Health Organization (WHO). Pulse Survey on Continuity of Essential Health Services During the COVID-19 Interim report 27 August 2020. WHO; 2020. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO- 2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2020.1

- Ndugwa RP, Cleland J, Madise NJ, Fotso J-C, Zulu EM. Menstrual pattern, sexual behaviors, and contraceptive use among postpartum women in Nairobi urban J Urban Health. 2011;88(2):341-355. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11524-010-9452-6

- World Health Organization (WHO). Programming Strategies for Postpartum Family Planning. WHO; 2013. Accessed October 5, https://www.who. int/publications/i/item/9789241506496

- High Impact Practices in Family Updated October 2020. Accessed October 5, 2022. http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/high-impact- practices-in-family-planning-list

- Rossier C, Hellen Traditional birthspacing practices and uptake of family planning during the postpartum period in Ouagadougou: qualitative results. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;40(2):87-94. https://doi.org/10.1363/4008714

- Dev R, Kohler P, Feder M, Unger JA, Woods NF, Drake A systematic review and meta-analysis of postpartum contraceptive use among women in low- and middle- income countries. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0824-4

- Winfrey W, Rakesh Use of Family Planning in the Postpartum Period. ICF International; 2014. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://dhsprogram.com/ publications/publication-cr36-comparative-reports.cfm

- Caleb-Varkey L, Mishra A, Das A, et al. Involving Men in Maternity Care in India. Frontiers in Reproductive Health Program, Population Council; 2004. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/ departments_sbsr-rh/420/

- Abdel-Tawab NG, Loza S, Zaki Helping Egyptian Women Achieve Optimal Birth Spacing Intervals Through Fostering Linkages Between Family Planning and Maternal/Child Health Services. Population Council; 2008. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/ departments_sbsr-rh/389/

- Ahmed S, Ahmed S, McKaig C, et The effect of integrating family planning with a maternal and newborn health program on postpartum contraceptive use and optimal birth spacing in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plann. 2015;46(3):297-312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2015.00031.x

- Soliman M. Impact of antenatal counselling on couples’ knowledge and practice of contraception in Mansoura, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5(5):1002-1013.

- Delivery care: Each year, millions of births still occur without any assistance from a skilled attendant despite recent progress. UNICEF Data: Monitoring the Situation of Children and Updated July 2022. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://data.unicef. org/topic/maternal-health/delivery-care

- Indicator: Percentage of live births in the five (or three) years preceding the survey delivered at a health facility. STATcompiler, The DHS Accessed October 5, 2022. http://www.statcompiler.com/

- World Health Organization (WHO). Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive 5th ed. WHO; 2015. Accessed October 5, 2022. http:// www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/ family_planning/MEC-5/en/

- Maternal and Child Survival Program. Pathway of Opportunities for Postpartum Women to Adopt Family Jhpiego; 2015. Accessed October 5, 2022. http://www.mcsprogram.org/resource/pathway-of-opportunities-for-postpartum- women-to-adopt-family-planning/

- Castadot RG, Sivin I, Reyes P, Alers JO, Chapple M, Russel The international postpartum family planning program: eight years of experience. Rep Popul Fam Plann. 1975;(18):1-53.

- de Caestecker L, Banks L, Bell E, Sethi M, Arulkumaran S. Planning and implementation of a FIGO postpartum intrauterine device initiative in six countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143(Suppl 1):4-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12598

- Makins A, Taghinejadi N, Sethi M, et al. Factors influencing the likelihood of acceptance of postpartum intrauterine devices across four countries: India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143(Suppl 1):13-19. https://doi. org/10.1002/ijgo.12599

- Weerasekera DS, Senanayeke L, Ratnasiri PU, et al. Four years of the FIGO postpartum intrauterine device initiative in Sri Lanka: Pilot initiative to national policy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143(Suppl 1):28-32. https://doi.org/10.1002/ ijgo.12601

- Bhadra B, Burman SK, Purandare CN, Divakar H, Sequeira T, Bhardwaj The impact of using nurses to perform postpartum intrauterine device insertions in Kalyani Hospital, India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143(Suppl 1):33-37. https://doi.org/10.1002/ ijgo.12602

- Muganyizi PS, Kimario G, Ponsian P, Howard K, Sethi M, Makins Clinical outcomes of postpartum intrauterine devices inserted by midwives in Tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143(Suppl 1):38-42. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12603

- Thapa K, Dhital R, Karki YB, et Institutionalizing postpartum family planning and postpartum intrauterine device services in Nepal: role of training and mentorship. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143(Suppl 1):43-48. https://doi.org/10.1002/ ijgo.12604

- Fatima P, Antora AH, Dewan F, Nash S, Sethi M. Impact of contraceptive counselling training among counsellors participating in the FIGO postpartum intrauterine device initiative in Bangladesh. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143(Suppl 1):49-55. https:// doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12605

- Achyut P, Mishra A, Montana L, Sengupta R, Calhoun LM, Nanda P. Integration of family planning with maternal health services: an opportunity to increase postpartum modern contraceptive use in urban Uttar Pradesh, J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2016;42(2):107-https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2015-101271

- Bolam A, Manandhar D, Shrestha P, Ellis M, Malla K, Costello A. Factors affecting home delivery in the Kathmandu Valley, Health Policy Plann. 1998;13(2):152-158.

- Speizer IS, Calhoun LM, Hoke T, Sengupta R. Measurement of unmet need for family planning: longitudinal analysis of the impact of fertility desires on subsequent childbearing behaviors among urban women from Uttar Pradesh, India. Contraception. 2013;88(4):553-560. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC3835184/

- Tawfik Y. Integrating postpartum family planning using quality improvement in Afghanistan. Unpublished data; 2016.

- Tawfik Y, Rahimzai M, Ahmadzai M, Clark PA, Kamgang E. Integrating family planning into postpartum care through modern quality improvement: experience from Afghanistan. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2(2):226-233. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC4168614/

- Medina R, Vernon R, Mendoza I, Aguilar Expansion of Postpartum/Postabortion Contraception in Honduras. Population Council; 2001. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnacm374.pdf

- Vernon R, López-Canales JR, Cárcamo JA, Galindo The impact of a perinatal reproductive health program in Honduras. Int Fam Plann Perspect. 1993:19(3):103-109. https://doi. org/10.2307/2133244

- Pilihanku (My Choice) [Jhpiego/Indonesia]. Unpublished data; 2017.

- Boucar M, Sabou D, Saley Z, Hill K. Using Collaborative Improvement to Enhance Postpartum Family Planning in University Research Co., LLC; 2016. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://pdf. usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00M8C6.pdf

- Using collaborative improvement to enhance postpartum family planning in Niger. Unpublished data; 2017.

- Ingabire R, Nyombayire J, Hoagland A, et Evaluation of a multi-level intervention to improve postpartum intrauterine device services in Rwanda. Gates Open Res. 2019;2:38. https://doi. org/10.12688/gatesopenres.12854.3

- Casey SE, Chynoweth SK, Cornier N, Gallagher MC, Wheeler Progress and gaps in reproductive health services in three humanitarian settings: mixed-methods case studies. Confl Health. 2015;9(Suppl 1):S3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-S3

- Ho LS, Wheeler Using program data to improve access to family planning and enhance the method mix in conflict-affected areas of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018;6(1):161-177. https://doi.org/10.9745/ GHSP-D-17-00365

- Gallagher MC, Morris CN, Fatima A, Daniel RW, Shire AH, Sangwa BMM. Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception: a comparison across six humanitarian country contexts. Front Glob Womens 2021;2:613338. https://doi. org/10.3389/fgwh.2021.613338

- Ahmed S, Norton M, Williams E, et Operations research to add postpartum family planning to maternal and neonatal health to improve birth spacing in Sylhet District, Bangladesh. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2013;1(2):262-276. https://doi. org/10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00002

- Ahmed S, Ahmed S, McKaig C, et The effect of integrating family planning with a maternal and newborn health program on postpartum contraceptive use and optimal birth spacing in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plann. 2015;46(3):297-312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2015.00031.x

- Pfitzer A, Mackenzie D, Blanchard H, et al. A facility birth can be the time to start family planning: postpartum intrauterine device experiences from six Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;130(Suppl 2):S54-S61. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.03.008

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Adolescent-Responsive Contraceptive Services: Institutionalizing Adolescent-Responsive Elements to Expand Access and Choice. HIPs Partnership; https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/ adolescent-responsive-contraceptive-services

- Daniel E, Hainsworth G, Kitzantides I, Simon C, Subramania PRACHAR: Advancing Young People’s Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in India. Pathfinder India; 2016. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.pathfinder.org/wp- content/uploads/2016/11/PRACHAR-Advancing- Young-Peoples-Sexual-and-Reproductive-Health-and- Rights-in-India.pdf

- Balde A BR, Chau K, Cole C, Simon C, Tomasulto Toucher les jeunes femmes mariées et les parents pour la première fois pour la planification et l’espacement idéal des grossesses au Burkina Faso. Pathfinder International Guinée; 2015. Accessed October 5, https://www.pathfinder.org/wp-content/ uploads/2016/09/Toucher-les-Jeunes-Femmes- Mariees-et-les-Parents-Pour-la-Premiere-Fois-Pour-la- PEIGS-au-Burkina-Faso.pdf

- Chau K, Benevides R, Cole C, Simon C, Baldé A, Tomasulo A. Toucher les parents pour la première fois et les jeunes femmes mariées pour la planification et l’espacement idéal des grossesses pour la santé au Burkina Faso: résultats clés de la mise en œuvre du projet de Pathfinder International “Projet de Renforcement de l’Accès des Jeunes et Adolescents aux Services de Santé Sexuelle et Reproductive”. Projet Evidence to Action/Pathfinder International; 2015.

- SG, Nour SA, Kames MA, Yones Emergency contraceptive pills as a backup for lactational amenorrhea method (LAM) of contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2013;87(3):363-369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. contraception.2012.07.013

- Cleland J, Shah IH, Daniele M. Interventions to improve postpartum family planning in low‐and middle‐income countries: program implications and research Stud Fam Plann. 2015;46(4):423 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728- 4465.2015.00041.x

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Engaging Men and Boys in Family Planning: A Strategic Planning USAID; 2018. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.fphighimpactpractices. org/guides/engaging-men-and-boys-in-family- planning/

- Williams P, Santos N, Azman-Firdaus H, et al. Predictors of postpartum family planning in Rwanda: the influence of male involvement and healthcare experience. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01253-0

- Willcox ML, Mubangizi V, Natukunda S, et al. Couples’ decision-making on post-partum family planning and antenatal counselling in Uganda: a qualitative PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0251190. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251190

- Yargawa J, Leonardi-Bee J. Male involvement and maternal health outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(6):604-612. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204784

- Abdulkadir Z, Grema BA, Michael GC, Omeiza Effect of antenatal couple counselling on postpartum uptake of contraception among antenatal clients and their spouses attending antenatal clinic of a northern Nigeria tertiary hospital: a randomized controlled trial. West Afr J Med. 2020;37(6):695-702.

- Harrington EK, McCoy EE, Drake AL, et al. Engaging men in an mHealth approach to support postpartum family planning among couples in Kenya: a qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0669-x

- Lathrop E, Telemaque Y, Goedken P, Andes K, Jamieson DJ, Cwiak Postpartum contraceptive needs in northern Haiti. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112(3):239-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ijgo.2010.09.012

- Telemaque Y LE, Leconte C, Kimonian K, Kuhn C, Nickerson N. Postpartum family planning in northern Haiti: evaluation of a pilot Unpublished; 2017.

- Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCHIP), Population Services International (PSI). PPIUD Services: Start-Up to Scale-Up Regional Meeting, Burkina Faso, February 3-5, 2014: Meeting MCHIP; 2014. Accessed October 5, 2022. https:// pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00JXWK.pdf

- Kestler E, Orozco MdR, Palma S, Flores Initiation of effective postpartum contraceptive use in public hospitals in Guatemala. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2011;29(2):103-107.

- Chitashvili T, Holschneider S, Clark Improving Quality of Postpartum Family Planning in Low- Resource Settings: A Framework for Policy Makers, Managers, and Medical Care Providers. University Research Co., LLC; 2016. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.usaidassist.org/sites/assist/files/ improving_quality_of_ppfp_apr_2016.pdf

- Guide women through their postpartum family planning options. World Health Accessed October 5, 2022. https://postpartumfp.srhr. org/

- Postpartum family planning (PPFP) Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.k4health.org/toolkits/ ppfp

- Bangladesh: behavioral maintenance and follow-up. Service communication implementation Health Communication Capacity Collaborative. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://sbccimplementationkits. org/service-communication/case-studies/case-study-behavioral-maintenance-and-follow-up-in- bangladesh/

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Immediate postpartum family planning: a key component of childbirth care. Washington, DC: HIP Partnership; 2022 May. Available from: https://www. fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/immediate-postpartum- family-planning/

Acknowledgements

This brief was written by Elaine Charurat, Douglas Huber, Eva Lathrop, Trish MacDonald, Suzanne Mukakabanda, Rachel Yodi, and Linnea Zimmerman. It was updated from a previous version, available here. This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Afeefa Abdur-Rhaman, Ribka Amsalu, Bethany Arnold, Michal Avni, Maggwa Baker, Neeta Bhatnagar, Rosanna Buck, Megan Christofield, Arzum Ciloglu, Kim Cole, Temple Cooley, Chelsea Cooper, Carmela Cordero, Ana Cuzin, Peggy D’Adamo, Aachal Devi, Ellen Eiseman, Mario Festin, Coley Gray, Karen Hardee, Nuriye Hodoglugil, Caroline Jacoby, Emily Keyes, Joan Kraft, Cate Lane, Samantha Lint, Ricky Lu, Sara Malakoff, Shawn Malarcher, Janet Meyers, Erin Mielke, Pierre Moon, Dani Murphy, Winnie Mwebesa, Maureen Norton, Gael O’Sullivan, Saiqa Panjsheri, Alice Payne Merritt, Anne Pfitzer, May Post, Shannon Priyor, Heidi Quinn, Setara Rahman, Laura Raney, Elizabeth Sasser, Ritu Schroff, Caitlin Shannon, Willy Shasha, Jim Shelton, John Stanback, Sara Stratton, Caitlin Thistle, Carroll Vasquez, Michelle Weinberger, Jessica Williamson, and Melanie Yahner.

The World Health Organization/Department of Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception.

The HIP Partnership is a diverse and results-oriented partnership encompassing a wide range of stakeholders and experts. As such, the information in HIP materials does not necessarily reflect the views of each co-sponsor or partner organization.

To engage with the HIPs please go to: https://www. fphighimpactpractices.org/engage-with-the-hips/.