Digital Health for Systems: Strengthening Family Planning Systems Through Time and Resource Efficiencies

Use digital technologies to support health systems and service delivery for family planning.

A community health worker uses D-tree International’s mobile application to provide comprehensive family planning services to a client in Shinyanga, Tanzania. ©2015 Ueli Litscher, Courtesy of Photoshare

Background

Countries are turning to digital health applications through technologies such as mobile phones, tablets, and computers to improve health care delivery, strengthen health systems, and support clients. Experts believe such approaches can contribute toward time and resource efficiencies by improving our ability to bridge physical distance and by increasing accuracy and speed of data collection and reporting. With the rapid expansion of mobile and electronic platforms across the globe, including in low-and middle-income countries,1 there is potential for even greater use of digital health technologies to strengthen health systems and family planning service delivery.

This brief summarizes the experience and evidence for the most commonly used digital health technologies aimed at supporting health systems and providers. A companion brief will address applications aimed at supporting consumers.

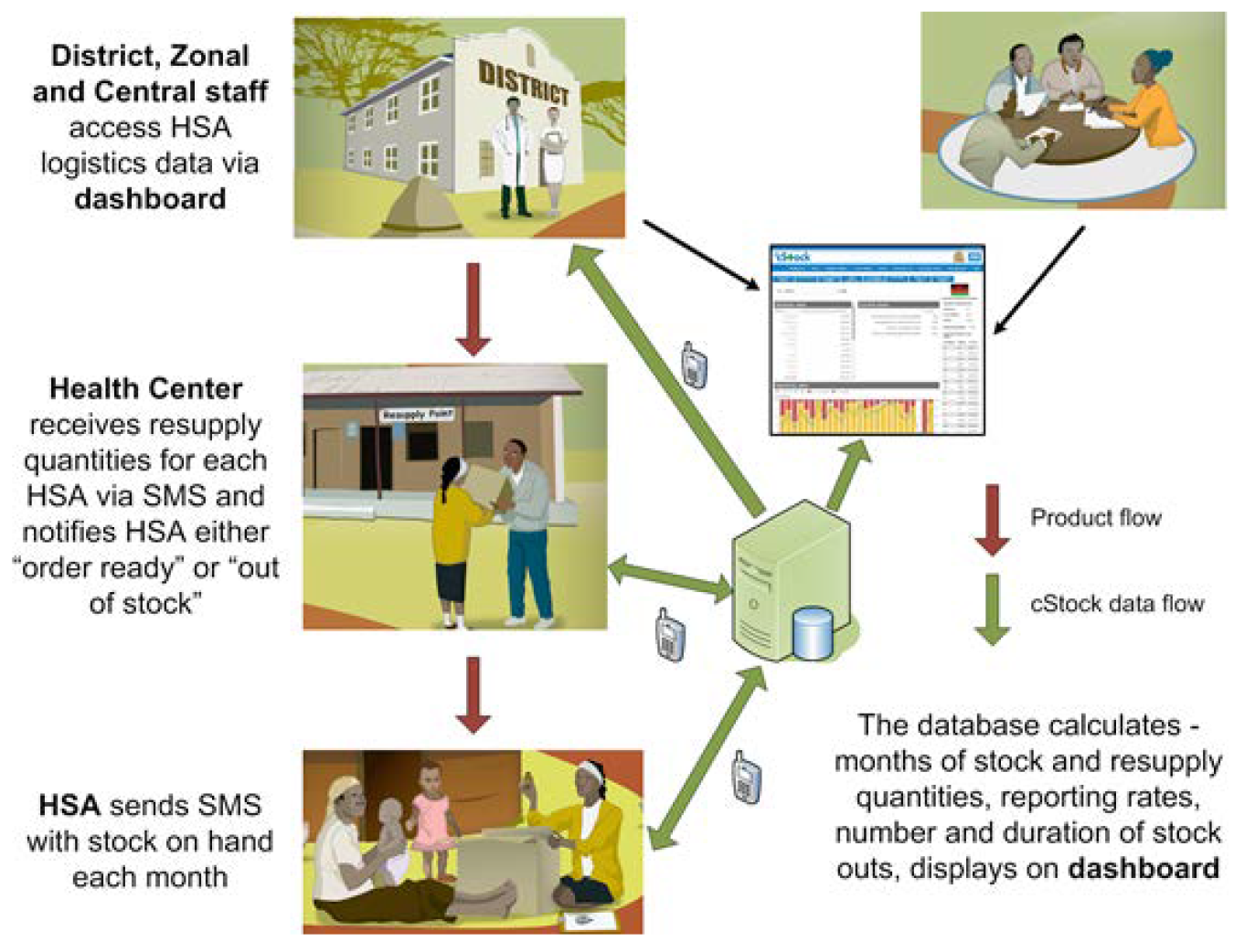

cStock Data and Product Flow

Source: Matthew Baek and Sarah Andersson, sc4ccm website, JSI. Accessed September 13, 2017

Key Messages

- Family planning indicators should be incorporated into new and existing digital health and logistics management information systems.

- More research is needed about when and how digital applications for provider support are most effective, efficient, and scalable.

- Mobile money and electronic financial transactions have the potential to provide efficiency and transparency of health care financing and transactions.

Digital health applications for health systems and providers can support implementation of High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs) by offering:

- Better data for decision making with virtually real-time reporting of services and commodities through a health management information system (HMIS) and logistics management information system (LMIS)

- Improved provider capacity through continuous learning, digital provider tools, and mobile supervision

- Increased transparency, efficiency, and accountability through digital financial services

Table 1 provides some illustrative examples of how digital technologies can be used to support implementation of HIPs.

Evidence demonstrating the value of digital health approaches has increased over the past decade. Systematic reviews of digital applications in HIV care and treatment, maternal and child health service delivery, and noncommunicable disease treatment have documented evidence that digital health tools increase efficiency of data collection, improve quality of care, and increase communication between health workers and their managers and supervisors.2-4 It is likely that these results are generalizable to family planning programming as well.

Illustrative Examples of How Digital Technologies Can Enhance HIPs

| High-Impact Practice | Combined With Digital Technology Enhancement | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Community health workers | Refresher training messages, communication with supervisor, and reporting, typically via SMS | Improved provider capacity and quality of care Time and energy savings when training service providers |

| Galvanizing commitment | Mobile money (electronic transfer of funds) | Efficient, accountable, transparent financial transactions |

| Supply chain management | Reporting via SMS to logistics management information system (LMIS) on stock and stock-outs | Reduced stock-outs of commodities Better data for decision making with virtually real-time reporting of services and commodities through the health management information system (HMIS) and LMIS |

| Leadership and management | Data collection through use of digital technology | Allows for virtually real-time monitoring for better decision making |

Digital health has been identified as a HIP enhancement by the HIPs technical advisory group.5 When scaled up and institutionalized, HIPs will maximize investments in a comprehensive family planning strategy. A HIP enhancement is a practice that can be implemented in conjunction with HIPs to further intensify the impact of the HIPs. While there are some initial experiences implementing digital health technologies, more research and documentation is needed to better understand the potential and limitations of this approach. For more information about HIPs, https://fphighimpactpractices.org/overview.

How can digital technologies enhance HIPs?

Better Data for Decision Making

Digital applications can be used to manage logistics and reduce contraceptive stock-outs. A common aim of digital technologies for family planning is to reduce contraceptive stock-outs. (See related HIPs brief on Supply Chain Management.) For example, in Malawi, community health workers (CHWs) use their personal phones to submit stock information via SMS to the LMIS. The system automatically calculates the resupply needs for a CHW based on reported stock levels, calculates how much stock was consumed and how much is needed for resupply, and transmits this need via SMS to the corresponding health center, enabling staff to prepackage orders in advance of the CHW pickup. This digital technology improved rates of reporting on stock levels and reduced the time required for drug resupply by half.6,7

Similar gains were reported in Bangladesh where an electronic LMIS collects data on consumption and availability of family planning commodities, sends SMS and email alerts for reporting reminders, tracks reports against set timelines, and sends warnings of potential stock imbalances for contraceptive commodities. Participant districts nearly eliminated stock-outs; for instance, facilities reporting stock-out rates for Implanon implants dropped from 69% to 1% among facilities using the digital system.8

Senegal is expanding use of the Informed Push Model, which allows logistics professionals to enter commodity stock information on tablets at the time of delivery. The program automatically calculates quantities based on previous consumption.7

Digital national health management information systems allow for timely analysis, data visualization, and reporting. Many countries are investing in large digital HMISs, such as the District Health Information Systems 2 (DHIS 2), and in digital human resource information systems such as Health Workforce Information Solutions (iHRIS) (see Table 2). These digital health information systems, often complemented by interactive data dashboards with GIS mapping, enable timely access to nationwide data that can be used to inform more granular decisions about how to allocate resources, where to target interventions, and whether to adjust performance objectives. Although DHIS 2 and iHRIS can and should include family planning indicators and data, not all countries are currently fully leveraging these platforms to capture this information.

Illustrative Examples of Digital Health Information Systems

| Health Information Systems | Description | Content | Current Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| District Health Information Systems 2 (DHIS 2) https://www.dhis2.org/ | Free, open-source national or sub-national health information system for program monitoring and evaluation |

|

Available in 47 countries |

| Health Workforce Information Solutions (iHRIS) https://www.ihris.org/ | Free, open-source software for managing health workforce information |

|

Available in 19 countries and supports more than 900,000 health worker records |

| Open Medical Record System (OpenMRS) http://openmrs.org/ | Free, open-source medical record system platform | Patient tracking and management | Available in 80 countries and has more than 6.3 million patient records |

Improved Provider Capacity

As a complement to in-person trainings, digital applications can improve clinical knowledge through refresher trainings and continuous learning opportunities for remote service providers. In Senegal, family planning service providers received refresher trainings on basic mobile phones through interactive voice response (IVR). Participants demonstrated significant gains in knowledge up to 10 months after trainings ended.9 In Nigeria, a program used Android-based smartphones or tablets to provide entertaining and instructional videos using footage of midwives providing family planning services. Qualitative interviews revealed that the video content raised awareness among midwives of how provider bias negatively affects clients.8 While the evidence base suggests that digital technologies can contribute to improved knowledge retention among providers, experts believe that these approaches can also provide time and resource efficiencies by reducing the need to travel for trainings, thereby additionally reducing disruptions to service delivery.

Digital applications may improve client-provider interactions by offering on-demand, comprehensive, and accurate information and referrals. Digital health is commonly used to enhance client-provider interactions and adherence to recommended protocols, particularly among CHWs. For example, in Benin, a mobile application enables CHWs to register women as family planning clients, provide family planning counseling and advice using a combination of images and audio messages in the local language, register clients’ chosen contraceptive method, share information on possible side effects of the method chosen, and record any family planning products distributed.10 CHWs in India reported that similar tools increased their confidence in performing their job.11 In Tanzania, CHWs reported that a mobile job aid with forms for client and service data and text-message reporting and reminders allowed them to provide timelier and more convenient care; offer better quality of information on a range of contraceptive methods; and improve privacy, confidentiality, and trust with clients.12 Over time, the Tanzania pilot evolved and scaled to include additional functionalities to support a pay-for-performance initiative and allow clients to rate service quality. The expanded program demonstrated a 522% increase in the number of monthly registrations of users who had received family planning counseling, and a 15-fold increase in the number of follow-up visits when comparing mobile to paper-based systems.8

In addition to supporting CHWs’ interactions with their clients, mobile phones are also used to link clients to clinical services, including provision of methods not offered by CHWs. Mobile-phone referrals, often made via SMS, have the potential to provide efficient links to clinical services and to support provider tracking.13

Digital applications may provide a cost-effective option for remote supportive supervision. In Malawi, CHWs used SMS to request specific technical information from district managers on topics such as adverse drug effects, management of contraceptive side effects, and dosage amounts. SMS participants reported and received feedback from their supervisor at least 5 times per month at an average of US$0.61 per communication. In comparison, those with cell phones but no access to SMS received feedback from their supervisors 4 times per month at US$2.70 per contact and those in the control group without any cell phone access received supervisor feedback 6 times per month at US$4.56 per in-person contact.6 In Kenya, CHWs used a popular instant messaging technology to enact virtual one-to-one, group, and peer-to-peer forms of supervision and support.14

Using digital technologies to track provider activities may improve performance. In Tanzania, SMS feedback from supervisors informed by data collected via a digital reporting system improved timeliness of CHW visits compared with CHWs who did not use the digital tracking system.16 Providers in India who used a digital self-tracking tool made 20% more visits than providers who did not use the tool.11

Improved Efficiency, Accountability, and Transparency of Financial Transactions

Mobile money can be leveraged to increase efficiency and transparency of financial transactions. Digital financial services use mobile technology to store, send, or receive funds and are increasingly being applied across the health sector to replace cash-based transactions. Applications include bulk payments, such as salaries and per diems, as well as delivery of timely incentive payments for service referrals through results-based financing schemes. In Madagascar, a mobile money program used to facilitate payments to family planning service providers significantly reduced the time delay for reimbursement.16 The rapid claims reimbursements also increased service provider motivation to offer quality services and expand their client base.17 In Bangladesh, a program uses mobile money to reimburse providers for delivering maternal and child health services. The switch from cash to digital transfers resulted in an annual cost savings of approximately US$60,000 and an annual time savings of roughly 41,333 work hours.17

Resource-tracking heat maps are an innovation that allows stakeholders to visually follow the flow of money through the health system. The system can be designed to identify funding bottlenecks, assess the timeliness of disbursements, and expose leakage in the system.18

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

Gather information about and from the intended users of the digital interventions. This includes questions related to how stakeholders currently understand and use technology (including the types of technology they use and prefer and how they pay for technology use), as well as the barriers they face that a digital solution might address. Segmenting users into sub-categories (e.g., men/women, educated/non-educated) can provide insight into important differences that could influence the design of the digital health intervention.19 Once it has been established that a digital solution is appropriate for solving a given problem, engage users, as well as other key stakeholders, in the design and testing of the tool.20 Doing so can help create more appropriate and user-friendly interventions that are more likely to be adopted, while failing to do so can mean costly and timely revisions later down the line.21

In Bangladesh, implementers learned that even a visually engaging dashboard with actionable data—but one created without input from end-users—did not sufficiently guarantee effective data use at the local level. To address this, the project incorporated scheduled SMS features and email alerts to push data to those who were entering it and to their supervisors. This push notification system facilitated the transition process from having a “data-producing role” to employing a “data-use culture,” thus improving decentralized decision making.8 This experience also illustrates the importance of providing orientation, training, and support to those who are expected to use the digital health application so they are comfortable and knowledgeable about how to use the application itself as well as the data that the application produces in order to improve programming.

Understand the overall technology landscape, including available infrastructure, existing programs, opportunities for interoperability, and potential technology partners. It is important to collect information about the technology landscape, including cell phone and Internet coverage, to make decisions about what type of technology will be most appropriate. In addition, time and resources can be saved when building upon existing digital services to add new functionalities (especially when the intervention is built on open-source software) and when ensuring that digital health interventions are interoperable, meaning they can “talk” to each other to exchange information. Increasingly, decision makers and implementers are seeking to create links among different digital health systems and services to further achieve systems-level outcomes and impact.22,24 In Tanzania, a mobile phone-based family planning screening and counseling job aid for CHWs was created within an existing mobile phone-based HIV counseling tool rather than building a separate tool on a different platform, thus leveraging existing resources and facilitating family planning and HIV integration in service delivery.24 Many mobile digital platforms, such as those that offer counseling and screening tools for providers, also collect data regarding number of clients per method or products distributed and are becoming compatible with HMIS software such as DHIS 2 so that health indicators, including for family planning, can be incorporated and reported on at the national level. Familiarity with national data security and privacy standards can help to build digital systems that are compliant.

Determine the potential scale for the project and the resources necessary for its long-term operation. As the field of digital health matures, more interventions are reaching scale—used by large numbers of individuals or at national or near-national levels of coverage, and institutionalized into existing systems and processes with high levels of engagement and ownership by local stakeholders. Successful projects have engaged local stakeholders from the beginning in a deliberate, systematic, and continuous process.25 A contraceptive stock tracking application in Malawi achieved scale up by getting Ministry of Health endorsement, creating a dedicated task force, and maintaining close engagement and coordination with partners, including mobile network operators, resulting in government ownership and administration of the system.6

Consider realistic options for sustainable financing. Digital health interventions need to be developed in a way that is appropriate to the local context while at the same time considering cost implications should the project be scaled nationally. Costs can include program design, equipment procurement, hosting fees, short-code fees, data packages, and server maintenance. Different approaches are associated with different financial and technical support implications, whether using smartphone applications, SMS, or voice. For example, interventions that use SMS can become costly as they scale—the more SMS sent and received, the higher the cost. While some services have succeeded in obtaining reduced or free SMS, voice, and/or data rates through public-private partnerships, most do not, and governments may not be in a position to assume the costs as projects transition to national scale. Furthermore, programs may want to explore other less costly platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp. Regardless of the technology, if digital health interventions are proven to be more cost-effective than non-digital alternatives, or to bring cost-efficiencies, then governments may successfully advocate for internal or external funding assistance.

Monitor the implementation and performance of your digital health service. Like all health interventions, monitoring and evaluation should be planned for from the start as part of program design and should be linked to the program’s logic model. What is unique to digital health technologies is the ability to rapidly collect monitoring and evaluation data through various techniques, including through routine system data as well as through other quantitative and qualitative approaches such as surveys deployed via the digital platform. The ability to garner near real-time process monitoring information enables rapid design and implementation improvements. In addition, if designed well, evaluations of digital health interventions can determine their effectiveness, including value for money, as well as impact, though these evaluations may or may not be conducted using only digital data collection methodologies.20 Once ready to document and disseminate results from monitoring and evaluation, implementers may find the mHealth Evidence Reporting and Assessment (mERA) Checklist, developed by the mHealth Technical Evidence Review Group at the World Health Organization,27 to be a useful resource.

© 2015 PMA2020/Shani Turke, Courtesy of Photoshare

Priority Research Questions

These research questions, reviewed by the HIPs technical advisory group, reflect the prioritized gaps in the evidence base specific to the topics reviewed in this brief and focus on the HIPs criteria.

- In what circumstances is the use of digital health interventions in family planning most cost-effective for offering training, training follow-up, or continuing education to providers?

- In what circumstances are digital health interventions most cost-effective for use in contraceptive counseling and screening?

- In what circumstances are digital health interventions in family planning cost-effective compared with non-digital interventions?

- Do digital applications that support family planning systems contribute to client-level outcomes such as the modern contraceptive prevalence rate?

Tools and Resources

Tools and Resources

- Principles for Digital Development: A set of nine principles based on lessons learned in implementing digital technologies in development.

- mHealth Planning Guide: A thorough orientation to the mHealth planning process for anyone looking to learn more about integrating mobile technology into health programs in low- and middle-income countries.

- mHealth Assessment and Planning for Scale (MAPS) Toolkit: A self-assessment tool that guides project teams to sustainably scale up their mHealth innovations.

- Global Digital Health Network: A networking forum for thousands of members from 94 countries to share information, engage with the broader community, and provide leadership in digital health for global public health.

- Former Digital Health HIPs brief entitled: mHealth: Mobile technology to strengthen family planning programs. This brief synthesized the evidence and offered tips for implementation as of 2013.

References

- Pew Research Center. Emerging nations embrace Internet, mobile technology: cell phones nearly ubiquitous in many countries. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2014. http://www.pewglobal.org/2014/02/13/emerging-nations-embrace-internet-mobile-technology/

- Amoakoh-Coleman MB, Borgstein A, Sondaal S. Effectiveness of mHealth interventions targeting health care workers to improve pregnancy outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Med Internet Research. 2016;18(8):e226. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5533

- Stephani V, Opoku D, Quentin W. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of mHealth interventions against non-communicable diseases in developing countries. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:572. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3226-3

- Catalani C, Philbrick W, Fraser H. mHealth for HIV treatment & prevention: a systematic review of the literature. Open AIDS J. 2013;7:17-41. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874613620130812003

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Family planning high impact practices list. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development; 2017. http://fphighimpactpractices.org/high-impact-practices-in-family-planning-list-2/

- Lemay N, Sullivan T, Jumbe B. Reaching remote health workers in Malawi: baseline assessment of a pilot mHealth intervention. J Health Commun. 2012;17(suppl 1):105-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2011.649106

- Haas S. mHealth compendium, special edition 2016: reaching scale. Arlington, VA: African Strategies for Health, Management Sciences for Health; 2016. http://www.unicefstories.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/mHealth-Compendium-Special-Edition-2016-Reaching-Scale-.pdf

- Levine R, Corbacio A, Konopka S, et al. mHealth compendium, volume 5. Arlington, VA: African Strategies for Health, Management Sciences for Health; 2016. https://www.msh.org/resources/mhealth-compendium-volume-five

- Diedhiou A, Gilroy KE, Cox CM, et al. Successful mLearning pilot in Senegal: delivering family planning refresher training using interactive voice response and SMS. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(2):305-21. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00220

- Center for Human Services. Texting for maternal wellbeing: use of mobile phones by CHWs to offer family planning services. Chevy Chase, MD: University Research Co., Center for Human Services; 2015. http://www.urc-chs.com/resources/texting-maternal-wellbeing-use-mobile-phones-chws-offer-family-planning-services

- Borkum E, Sivasankaran A, Sridharan S, Rotz D, et al. Evaluation of the information and communication technology (ICT) continuum of care services (CCS) intervention in Bihar. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research; 2015. https://www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/publications/evaluation-of-the-information-and-communication-technology-ict-continuum-of-care-services-ccs

- Braun R, Lasway C, Agarwal S, et al. An evaluation of a family planning mobile job aid for community health workers in Tanzania. Contraception. 2016;94(1):27-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2016.03.016

- Advancing Partners and Communities (APC). Situation analysis of community-based referrals for family planning. Arlington, VA: APC; 2016. https://www.advancingpartners.org/sites/default/files/technical-briefs/apc_situation_analysis_cbfp_brief.pdf

- Henry J, Winters N, Lakati A, et al. Enhancing the supervision of community health workers with WhatsApp mobile messaging: qualitative findings from 2 low-resource settings in Kenya. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4(2):311-325. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00386

- Flaming A, Canty M, Javetski G, Lesh N. The CommCare evidence base for frontline workers. Cambridge, MA: Dimagi; 2016. http://www.dimagi.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CommCare-Evidence-Base-July-2016.pdf

- Burke E, Gold J, Razafinirinasoa L, Mackay A. Youth voucher program in Madagascar increases access to voluntary family planning and STI services for young people. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(1):33-43. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00321

- Health Finance and Governance Project. Mobile money for health: case study compendium. Bethesda, MD: Abt Associates, Health Finance and Governance Project; 2015. https://www.hfgproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/HFG-Mobile-Money-Compendium_October-2015.pdf

- Switilick-Prose K, Ahmed R. Follow the money: how to increase the transparency, efficiency and accountability of health care spending. Devex Newswire. November 11, 2014. https://www.devex.com/news/follow-the-money-how-to-increase-the-transparency-efficiency-and-accountability-of-health-care-spending-84756

- Knowledge for Health (K4Health) Project. The mHealth planning guide: key considerations for integrating mobile technology into health programs. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, K4Health Project; 2014. https://www.k4health.org/toolkits/mhealth-planning-guide

- World Health Organization (WHO). Monitoring and evaluating digital health interventions: a practical guide to conducting research and assessment. Geneva: WHO; 2016. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/mhealth/digital-health-interventions/en/

- About. Principles for Digital Development website. http://digitalprinciples.org/about/

- Digital Health and Interoperability Working Group. Taming the wild west of digital health data: linking systems to strengthen global health outcomes. Health Data Collaborative; 2016. https://www.healthdatacollaborative.org/news/article/taming-the-wild-west-of-digital-health-data-linking-systems-to-strengthen-global-health-outcomes-79/

- World Health Organization (WHO). Directory of eHealth policies. Geneva: WHO; 2016. http://www.who.int/goe/policies/en/

- Agarwal S, Lasway C, Lengle K, et al. Family planning counseling in your pocket: a mobile job aid for community health workers in Tanzania. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4(2):300-310. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00393

- World Health Organization (WHO). The MAPS toolkit: mHealth assessment and planning for scale. Geneva: WHO; 2015. http://who.int/life-course/publications/mhealth-toolkit/en/

- Agarwal S, LeFevre A, Lee, J, et al; WHO mHealth Technical Evidence Review Group. Guidelines for reporting of health interventions using mobile phones: mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist. BMJ. 2016;352(1174). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1174

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Digital health: strengthening family planning systems. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development; 2017. Available from: https://fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/digital-health-systems/

Acknowledgments

This document was written by Nicole Ippoliti, Trinity Zan, Margaret D’Adamo, and Shawn Malarcher. Critical review and helpful comments were provided by Afeefa Abdur-Rahman, Michal Avni, Rita Badiani, Regina Benevides, Elaine Charurat, Arzum Ciloglu, Claire Cole, Ellen Eiseman, Heidi Good, Sherri Haas, Karen Hardee, Ishrat Husain, Joan Kraft, Alice Liu, Ricky Lu, Justin Maly, Emily Mangone, Cassandra Mickish Gross, Erin Mielke, Dani Murphy, Lisa Mwaikambo, Alice Payne Merritt, May Post, Heidi Quinn, Pam Riley, Ritu Schroff, Willy Shasha, Adam Slote, Sara Stratton, Caitlin Thistle, Reshma Trasi, Sarah Unninayar, Caroll Vasquez, Kimberly Waller, and Tim Wood.

This brief is endorsed by: Abt Associates, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, CARE, Chemonics International, EngenderHealth, FHI 360, FP2020, Georgetown University/Institute for Reproductive Health, International Planned Parenthood Federation, IntraHealth International, Jhpiego, John Snow, Inc., Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, Management Sciences for Health, Options, Palladium, Pathfinder International, Population Council, Population Reference Bureau, Promundo US, Public Health Institute, Save the Children, U.S. Agency for International Development, and University Research Co., LLC.

The World Health Organization/Department of Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIPs briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: http://www.who.int/topics/family_planning/en/.

For more information about HIPs, please contact the HIPs team.

Provide Comments

To provide comments on this brief, please fill out the form on the Community Feedback page.