Promoting healthy couples’ communication to improve reproductive health outcomes

Background

Couples’ communication is a form of interpersonal communication that entails the exchange or sharing of information, thoughts, ideas, intentions, and feelings between sexual partners. Couples’ communication is influenced by policies, attitudes, values, culture, social and gender norms, and the individual’s immediate environment. There are many forms of interpersonal communication that could result in uptake of modern contraception or improved reproductive health outcomes, e.g., between woman to woman; man to man; parent to child; provider to client; provider to provider; trusted adult to adolescent. This brief focuses on improving healthy couples’ communication to improve reproductive health outcomes.

Since the 1990s, the family planning field has recognized the importance of couples’ communication in the voluntary uptake of modern contraceptive methods.1–3 Several studies show a positive association between couples discussing their fertility intentions with joint decision making on whether or when to have children (Schwandt et al., 2021; Naja-Sharjabad, 2021; Shattuck, 2011).4–6

In the last decade, evidence has emerged on the importance of ensuring interventions promoting healthy couples’ communication, with a focus on improving the quality of those discussions6(p186) and addressing gender inequalities. Supporting healthy couples’ communication can increase the uptake of modern contraceptive use while meeting the HIP principle of “gender equality,” or “endeavor[ing] to be inclusive of women and men by removing barriers to their active engagement and decision-making, recognizing the role of family planning in supporting more equitable power dynamics and health relations.”7 Recently, there has been attention to power related to sexual decision making and healthy sexual relationships (e.g., consent, bodily autonomy, pleasure), with a need to “better support couples in building practical skills to increase intimacy and communication).”8(p5)

Access to modern contraceptive methods and reproductive autonomy are fundamental human rights.9 Individuals must be able to access contraception as their individual right. Involvement of the male partner should not prevent women from choosing contraception free from the influence of a male partner.6 Therefore, while promoting healthy couples’ communication to improve reproductive health outcomes is a proven HIP, it is critical to ensure that “all couples and individuals have the basic right to decide freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children.”9(p13)

Why is this practice important?

All couples can benefit from improved couples’ communication, enabling both partners to assess their own fertility goals and how to meet them. A study including West and Eastern and Southern Africa showed that agreement among spouses on waiting time to next birth was inconsistent.10 Therefore, active interventions are needed to promote healthy couples’ communication to achieve healthy spacing and timing of pregnancies, as well as other healthy behaviors. “Both men and women may fail to achieve their childbearing goals when there is a lack of communication.”11(p30) A study found that couples counseling on contraception helped male partners “realize that spacing pregnancies is directly related to the overall health and financial security of their family,” as well as leading to overall improvements in a marital relationship.12(p12) The needs of men and women do not have to be pitted against each other, but can be seen as complementary.13

Healthy couples’ communication can increase uptake of modern contraception and help couples achieve their fertility intentions. Studies show that partners often do not discuss family planning.14 Additionally, studies find discordant reports of contraceptive use.15 In six countries situated within Asia and Africa, a study of young couples found discordant fertility desires.16 A study of young couples in Niger found that 75% did not report discussion related to contraceptive use, but those who discussed contraceptive use were more likely to report contraceptive use overtly than covertly.17 Joint couple-level fertility desires are important for contraceptive use.16 Couples’ communication has been correlated with increased uptake of contraception.18–20

Promoting healthy couples’ communication can also impact gender equality. Fostering discussions between couples and using prompts that promote gender equality, have both increased use of contraception as well as increased gender equity.21,22 For example, in a study focused on transforming harmful gender norms,22 women reported that men in the intervention group had higher levels of participation in child care than men in the control group. Men may find it challenging to access accurate contraceptive information as most services are geared to women.23 Couples’ communication about contraception may help to bridge this gap as women share family planning information they may know and as couples become open to going to family planning services together.

What is the evidence that promoting healthy couples’ communication is high impact?

Numerous studies have shown a correlation between couples’ communication and uptake for modern contraception by both men (e.g., uptake of vasectomy) and women.18–33 A number of evidence-informed interventions have promoted healthy couples’ communication to increase uptake of modern contraceptive use. Many of these evidence-informed interventions have simultaneously addressed issues of unequal gender norms so that women have a more effective voice in stating their contraceptive needs and gaining partner agreement for their use.

Successful social behavior change (SBC) efforts to improve healthy couples’ communication that have also resulted in uptake of modern contraception have been documented through: counselling sessions with couples21,34; reaching men through trained peer educators5; participatory small group discussions22; mass media35; TV advertisements36; serial radio dramas37 and trained staff.38,39 These evidence-informed interventions are listed in Table 1 and in the Appendix.*

The Table shows a range of SBC interventions with strong evidence and a diversity of countries represented. The Appendix includes additional evidence.

Selected findings with evidence informed interventions for healthy couples’ communication that has increased uptake of modern contraception.

| SBC Intervention | Couple Communication | Contraceptive Uptake | GBV/gender equality |

|---|---|---|---|

| India (Raj et al., 2016)21 | |||

| The CHARM intervention entailed three family planning and gender equity (FP+GE) counseling sessions for men and couples. Trained male village health care providers delivered the counseling sessions. | ✓ Women in the intervention group were more likely to report contraceptive communication at 9-month follow-up compared to the control group. | ✓ Women in the intervention group were more likely to report modern contraceptive use at 9 and 18-month follow-up compared to the control group. | ✓ Women in the intervention group were less likely to report sexual IPV at 18-month follow-up. ✓ Men in the intervention group were less likely than those in the control to report attitudes accepting of sexual and physical IPV at 18-month follow-up. |

| Malawi (Shattuck et al., 2011; Hartmann et al., 2012)5,40 | |||

| Peer counseling with male motivators provided information on modern FP options and local facilities offering these methods. Motivators facilitated discussions exploring “how rigid gender roles can lead to negative outcomes, challenging the notion that a large family is a sign of virility” (pg. 1090). | ✓ Frequency of discussing FP with one’s wife was positively associated with family planning uptake. | ✓ Increase in contraceptive use in the intervention group compared to the comparison group. | ✓ Men facilitated contraceptive use of their partners. ✓ Women reported an increase in shared decision-making. |

| Nigeria (Do et al., 2020)36 | |||

| Cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from the larger MTV Shuga evaluation. The SBC intervention assessed were family planning messages and advertisement on television. | ✓ Exposure to FP advertisement on TV in the last 30 days was shown to have a significant association with an increased likelihood of discussion among young people 15-24 who were sexually active (2.52 times more likely) with their partner. ✓ This in turn was associated with increased modern contraceptive use among young people 15-24 who were sexually active (2.73 times more likely). |

✓ Modern contraceptive use was almost three times higher among young people 15-24 who were sexually active who reported discussing FP with their partner than among those who did not discuss FP with their partner. Seeing FP advertisements on TV in the past 30 days was associated with higher FP discussion and modern contraceptive use among young people 15-24 who were sexually active. | Not assessed. |

| Kenya (Wegs et al., 2016)41 | |||

| Community-based facilitators organized community dialogues for single sex and mixed groups of participants from several villages. Topics included gender, sexuality, and FP. Community leaders and satisfied FP users acted as role models, sharing their support for “FP, equitable gender norms, open communication and shared decision-making regarding family planning between spouses” (pg. 3). | ✓ Spousal communication was associated with women’s use of modern FP. | ✓ At baseline 34% of women and 27.9% of men used modern FP methods; at endline, 51.2% of women and 52.2% of men used modern FP methods. ✓ Exposure to the intervention was associated with 1.78 times higher odds of using a modern FP method at endline compared to baseline for women but not for men. ✓ At endline men who reported high approval of FP and more gender equitable beliefs were more likely to use modern FP. |

X Women described some shifts towards more equitable household roles, and more joint decision-making (such as decisions about household purchases). Despite some shifts, women still did the majority of household work and men maintained most of decision-making power. |

| El Salvador (Lundgren et al., 2005)38 | |||

| ✓ Trained staff and volunteers incorporated FP information on Standard Days Method (SDM) in their educational activities for a water project, with messages on gender equality as well as the link between FP and water resources including two home visits with couples. | ✓ Both women and men reported significantly more discussions in the prior 6 months on the number of children, using an FP method, which FP method to use, men’s roles in FP, and the cycle of women’s fertility. | ✓ Men significantly increased their contraceptive uptake (SDM, condoms) following the intervention (63% compared to 44%); with the odds of reporting that they were using FP 1.68 times greater at endline. ✓ Women who participated in the project were significantly more aware of their cycle of fertility, increasing their bodily awareness. |

✓ Men in the community reported that man’s role in FP increased significantly from 5% to 23%. ✓ Women reported that the man’s role in FP increased significantly from 7% to 16%. |

✓: Statistically significant

X: Not statistically significant

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

SBC for healthy couples’ communication entails approaches such as creating an enabling environment, e.g., by creating spaces for couples to receive joint counseling. Another SBC approach addresses social change as much as individual behavior change, e.g., by providing role models that practice healthy couples’ communication. The following tips for design and implementation of interventions to improve interpersonal communication recognize that behavior is a function of the person and her/his environment.

- Address gender and power dynamics, including gender-based violence (GBV). Conduct formative research for couples’ communication interventions to explore how couples relate to each other, especially within intimate relationships. What is the distribution of power and authority? What are gender-specific norms within relationships? Use a gender-synchronized* approach to ensure that interventions are mutually reinforcing.42 Direct engagement in problem solving can help to strengthen couples’ communication.43

- Ensure that interventions “do no harm” to undermine women’s autonomy. Intimate partner violence has been associated with discordance in fertility intentions between men and women,44 with a number of implications. In certain studies, some women who reported experiencing GBV from their husbands were more likely to use contraception without informing their husbands.45–47 There are numerous reports of both women and men accessing modern contraceptive methods in secret or using clandestine methods such as injectables or intrauterine devices, fearing either coercion, disapproval, abandonment, or GBV from their partner.48–50 It is critical to ensure that in the context of promoting healthy couples’ communication, each person can individually access reproductive health information and services as well as services related to GBV as needed (Box 1).

- Norms of masculinity should be addressed. Women and men may differ in their belief of whether a woman has an independent right to use contraception.51 The decision-making power of a husband can significantly reduce women’s likelihood of using contraceptives,52,53 as harmful norms of masculinity in certain contexts may lead men to demonstrate their virility by fathering numerous children.54 When possible, it is important to incorporate discussions of sexual pleasure in the context of sex and contraception.6

- Find creative and culturally appropriate ways to address women’s and men’s skills and perceived self-efficacy to communicate with their partners effectively. If a person sees someone else performing a behavior but doubts their own ability to copy it, it is not likely that s/he will attempt the new behavior. In the case of couples communicating about family planning and reproductive health, individuals may need to learn and/or practice new skills before attempting to communicate with a partner. They will also need to have confidence that they can communicate without fear of conflict and/or other risks. For women in particular, programs may need to provide safe spaces for women to practice skills and possible prompts within a same sex group of trusted peers. For example, the CHARM study first provided separate safe spaces for married men, followed by a couples counseling session (Box 2).21

- Consider and plan for the special requirements and challenges of couples counseling sessions conducted in facilities and/or via outreach by community health workers (CHWs) to couples in their homes or elsewhere. Contraception may be a taboo subject, and auditory and visual privacy are essential for the couples who agree to joint counseling.

- Search out existing platforms and spaces where boys and men can access information about sex, sexual relationships, reproductive health, and family planning information and services. When framed appropriately, men’s groups like farmers groups or religious groups often welcome the chance to discuss family planning and reproductive health. Yet a recent review found that few country national plans addressed men’s roles in contraception comprehensively.23 Working with existing groups can be a more efficient and sustainable way to reach men and boys. Discussions around family planning should focus on family well-being plus family size and not just methods.6

- Provide opportunities and job aids for those who offer health and family planning services. Program providers benefit from learning and sharing best practices about how to serve and communicate effectively with female and male clients as well as couples as a unit. Pre-service and in-service training for providers as well as simple counseling tools/aids/checklists/apps can make counseling easier. Creative leave-behind materials distributed by CHWs (like this pamphlet designed for newlyweds in Egypt) help stimulate discussion and joint decision making. Policies that ensure that women who want their partners to accompany them to counseling sessions may invite them to do so are important and may facilitate healthy couples’ communication.

- Identify and provide opportunities for respected couples in the community to model and talk about their healthy communication habits. Individuals assess the risks and rewards of actions before trying them out. SBC programs may help individuals make this assessment by showcasing role model couples and their actions through radio dramas, personal testimonials, and community discussions. For example, Malawi Male Motivators were respected men in the community who were trained to provide counseling.5

- Use social networks over time to spread the innovation of healthy couples’ communication through training and other mechanisms. Successful SBC programs identify 1) how the audience thinks of couples who are communicating about sexual and reproductive health and family planning issues, 2) opinion leaders in the local network, and 3) messages that address concerns about healthy couples’ communication. Media representations of couples communicating should demonstrate the positive impact of healthy couples’ communication.

* A gender-synchronized approach is defined as working with both sexes in a mutually reinforcing way, to challenge restrictive gender norms, catalyzing the achievement of gender equality.55

An intervention to increase male involvement in family planning and couples counseling in Zimbabwe used media messages to reach men. Data from household surveys of 501 men and 518 women who were interviewed prior to the intervention, with a follow-up survey with 508 male and 508 females, were collected to evaluate the program. The messages in the campaign used football images and analogies, with wives as teammates, service providers as coaches, and small families as the goal. Twice as many men as women heard the ads. The analysis indicates that “respondents were 1.6 times more likely to use a modern family planning method if they were exposed to at least three components of the multimedia campaign,”56(p31) even while controlling for other variables. Both men and women reported increased discussion with spouses about family planning. However, the campaign, while increasing couples’ communication resulting in uptake of modern contraception, also resulted in a significant increase in men believing that they alone should take responsibility for choosing a method, getting family planning information, and going to a clinic to seek family planning services,56 reducing women’s autonomy and increasing gender inequality. A key lesson learned was that attention to gender and power dynamics is critical.

In preparing for the CHARM initiative in India, researchers used WHO guidelines57 on domestic violence to conduct assessments. Husbands and wives were surveyed privately and separately. All participants, prior to baseline, were provided basic family planning information and how to access services. All female participants were provided with information on services for domestic violence. Following the baseline assessment, husbands in the intervention group were linked to male village health care providers trained to implement the CHARM intervention. Village health providers used a flipchart that addressed gender-equity related barriers, such as the importance of shared family planning decision making plus the importance of respectful marital communication, particularly no spousal violence (see below in Tools and Resources for a description and link to the training manuals used by CHARM, and the Table and Appendix for impact of effectiveness).21,58 CHARM was developed by experts on family planning, gender, and GBV. To date, CHARM has resulted in statistically significant increases in contraceptive use and gender equity.

Implementation measurement

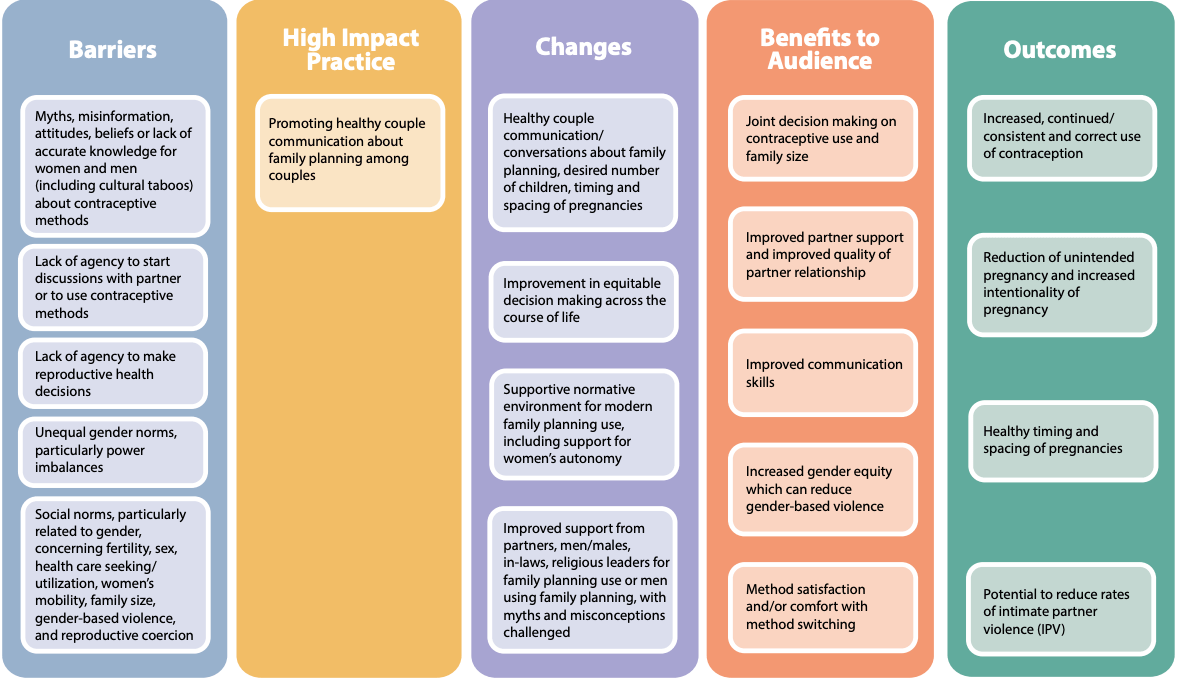

The following are illustrative indicators based on the Theory of Change that can be collected from a variety of data sources such as routine monitoring systems,59 remote mobile-based surveys,60 or household surveys such as PMA (https://www.pmadata.org/) and DHS (https://dhsprogram.com/).

- High Impact Practice: Number or percentage of intended audience who reported seeing family planning messages promoting communication among couples about family planning in the past three months by channel (e.g., social media, television, radio, community meetings).

- Changes: Number or percentage of intended audience who discussed contraceptive use with their partner in the past three months.

- Benefits to Audience: Percentage of women who state that use of modern contraception is their decision or a joint decision with their partner.

Priority research questions

- Do digital platforms successfully increase healthy couples’ communication?

- What programs and policies prepare adolescents to engage in healthy couples’ communication for fertility intentions?61

- Conduct cost-effectiveness studies to increase healthy couples’ communication that disaggregates how much various interventions cost.

- What programs and policies are effective in engaging couples in discussions related to healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies?62

- What are steps required to minimize potential negative impacts of couples counseling such as violence and reproductive coercion?48,49

- Save the Children. 2007. Male motivator training curriculum. The male motivator approach is designed to engage men to break down gender norms leading to male-initiated couples’ communication about family planning. Men who use modern contraception are identified and trained as male motivators and visit other men in the communities to provide information on contraception, plus practice skills to discuss fertility desires with wives.

- Rwanda Men’s Resource Center, Promundo-US and Rutgers WPF. 2013. Bandebereho Facilitator’s Manual: Kigali, Rwanda; Washington, DC, USA, Utrecht, The Netherlands. This tool is designed for participatory community engagement activities on gender equality, family planning, parenting, violence, and caregiving.

- UCSD. CHARM manual. This manual is designed to enhance the knowledge of health care practitioners on ways to address gender issues among young married couples in choosing and exercising their family planning options.

Note: If your program is addressing GBV in addition to healthy couples’ communication, there is a wealth of resources that you can consult, such as: https://prevention-collaborative.org; https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/07/respect-women-implementation-package and https://www.whatworks.co.za/

References

- Becker S. Couples and reproductive health: a review of couple studies. Stud Fam Plann. 1996;27(6):291–306. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2138025

- Jato MN, Simbakalia C, Tarasevich JM, Awasum DN, Kihinga CNB, Ngirwamungu E. the impact of multimedia family planning promotion on the contraceptive behavior of women in Tanzania. Int Fam Plann Perspectives. 1999;25(2):60. https://doi.org/10.2307/2991943

- Lasee A, Becker S. Husband-wife communication about family planning and contraceptive use in Kenya. Int Fam Plann Perspectives. 1997;23(1):15. https://doi.org/10.2307/2950781

- Schwandt H, Boulware A, Corey J, et al. An examination of the barriers to and benefits from collaborative couple contraceptive use in Rwanda. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01135-6

- Shattuck D, Kerner B, Gilles K, Hartmann M, Ng’ombe T, Guest G. Encouraging contraceptive uptake by motivating men to communicate about family planning: the Malawi Male Motivator project. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1089–1095. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300091

- Shand, T. Opportunities, Challenges and Countervailing Narratives: Exploring Men’s Gendered Involvement in Contraception and Family Planning in Southern Malawi. Ph.D. thesis. University College London; 2021.

- Principles underpinning high impact practices (HIPs) for family planning. High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Accessed Feb. 18, 2021. https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/principles-underpinning-high-impact-practices-hips-for-family-planning/

- Michau L, Namy S. SASA! Together: an evolution of the SASA! approach to prevent violence against women. Eval Program Plann. 2021;86:101918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2021.101918

- International Conference on Population and Development. Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development. 20th anniversary ed. United Nations Population Fund; 2014. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/programme_of_action_Web%20ENGLISH.pdf

- Gebreselassie T, Mishra V. Spousal agreement on preferred waiting time to next birth in sub-Saharan Africa. J Biosoc Sci. 2011;43(4):385–400. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932011000083

- Edmeades J, Mejia C, Parsons J, Sebany M. A Conceptual Framework for Reproductive Intentions: Empowering Individuals and Couples to Improve Their Health. International Center for Research on Women; 2018. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Reproductive-Empowerment-Background-Paper_100318-FINAL.pdf

- Stevanovic-Fenn N, Arnold B, Mathur S, Tier C, Pfitzer A, Lundgren R. Engaging Men for Effective Family Planning Through Couple Communication: An Assessment of Two MCSP Couple Approaches in Togo. Study Report. Population Council, Breakthrough RESEARCH; 2019. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Engaging-men-for-effective-FP-Togo.pdf

- Spindler E. Beyond the Prostate: Brazil’s National Healthcare Policy for Men (PNAISH). EMERGE Case Study 1. Promundo-US/Sonke Gender Justice/Institute of Development Studies; 2015. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/7057/EMERGE_CaseStudy1.pdf

- Azmat SK, Ali M, Ishaque M, et al. Assessing predictors of contraceptive use and demand for family planning services in underserved areas of Punjab province in Pakistan: results of a cross-sectional baseline survey. Reprod Health. 2015;12:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-015-0016-9

- Koffi AK, Adjiwanou VD, Becker S, Olaolorun F, Tsui AO. Correlates of and couples’ concordance in reports of recent sexual behavior and contraceptive use. Stud Fam Plann. 2012;43(1):33–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00300.x

- Speizer IS, Calhoun LM. Her, his, and their fertility desires and contraceptive behaviours: a focus on young couples in six countries. Glob Public Health. 2021;1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1922732

- Challa S, Shakya HB, Carter N, et al. Associations of spousal communication with contraceptive method use among adolescent wives and their husbands in Niger. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237512. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237512. Cited by: Speizer IS, Calhoun LM. Her, his, and their fertility desires and contraceptive behaviours: a focus on young couples in six countries. Glob Public Health. 2021;1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1922732

- Rosen JE, Bellows N, Bollinger L, Plosky WD, Weinberger M. 2019. The Business Case for Investing in Social and Behavior Change for Family Planning. Population Council, Breakthrough RESEARCH; 2019. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/20191211_BR_FP_SBC_Gdlns_Final.pdf

- Underwood C, Dayton L, Hendrickson Z. Concordance, communication, and shared decision-making about family planning among couples in Nepal: a qualitative and quantitative investigation. J Soc Pers Relat. 2019;37(2):357–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519865619

- Uddin J, Pulok MH, Sabah MN. Correlates of unmet need for contraception in Bangladesh: does couples’ concordance in household decision making matter? Contraception. 2016;94(1):18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2016.02.026

- Raj A, Ghule M, Ritter J, et al. Cluster randomized controlled trial evaluation of a gender equity and family planning intervention for married men and couples in rural India. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0153190. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153190

- Doyle K, Levtov RG, Barker G, et al. Gender-transformative Bandebereho couples’ intervention to promote male engagement in reproductive and maternal health and violence prevention in Rwanda: findings from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0192756. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192756

- Hook C, Hardee K, Shand T, Jordan S, Greene ME. A long way to go: engagement of men and boys in country family planning commitments and implementation plans. Gates Open Res. 2021;5:85. https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.13230.2

- Shattuck D, Wesson J, Nsengiyumva T, et al. Who chooses vasectomy in Rwanda? Survey data from couples who chose vasectomy, 2010-2012. Contraception. 2014;89(6):564–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2014.02.003

- Ankomah A, Oladosu, Anyanti. Myths, misinformation, and communication about family planning and contraceptive use in Nigeria. Open Access J Contracept. 2011:95. https://doi.org/10.2147/oajc.s20921

- Belda SS, Haile MT, Melku AT, Tololu AK. Modern contraceptive utilization and associated factors among married pastoralist women in Bale eco-region, Bale Zone, South East Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2115-5

- Estrada F, Hernández-Girón C, Walker D, Campero L, Hernández-Prado B, Maternowska C. Uso de servicios de planificación familiar de la Secretaría de Salud, poder de decisión de la mujer y apoyo de la pareja [Use of family planning services and its relationship with women’s decision-making and support from their partner]. Salud Publica Mex. 2008;50(6):472–481. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0036-36342008000600008

- Irani L, Speizer IS, Fotso JC. Relationship characteristics and contraceptive use among couples in urban Kenya. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;40(1):11–20. https://doi.org/10.1363/4001114

- Islam MS, Alam MS, Hasan, MM. Inter-spousal communication on family planning and its effect on contraceptive use and method choice in Bangladesh. Asian Soc Sci. 2013;10(2). https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n2p189

- Tilahun T, Coene G, Temmerman M, Degomme O. Couple based family planning education: changes in male involvement and contraceptive use among married couples in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:682. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2057-y

- Link CF. Spousal communication and contraceptive use in rural Nepal: an event history analysis. Stud Fam Plann. 2011;42(2):83–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2011.00268.x

- Wuni C, Turpin CA, Dassah ET. Determinants of contraceptive use and future contraceptive intentions of women attending child welfare clinics in urban Ghana [published correction appears in BMC Public Health. 2017 Sep 22;17 (1):736]. BMC Public Health. 2017;18(1):79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4641-9

- Sharan M, Valente T. Spousal communication and family planning adoption: effects of a radio drama serial in Nepal. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2002;28(1):16. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088271

- Ashraf N, Field E, Voena A, Ziparo R. How Education About Maternal Health Risk Can Change the Gender Gap in the Demand for Family Planning in Zambia. Grantee Final Report. International Initiative for Impact Evaluation; 2019.

- Hutchinson PL, Meekers D. Estimating causal effects from family planning health communication campaigns using panel data: the “your health, your wealth” campaign in Egypt. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e46138. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046138

- Do M, Hutchinson P, Omoluabi E, Akinyemi A, Akano B. Partner discussion as a mediator of the effects of mass media exposure to FP on contraceptive use among young Nigerians: evidence from 3 urban cities. J Health Commun. 2020;25(2):115–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2020.1716279

- Jah F, Connolly S, Barker K, Ryerson W. Gender and reproductive outcomes: the effects of a radio serial drama in northern Nigeria. Int J Popul Res. 2014;2014:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/326905

- Lundgren RI, Gribble JN, Greene ME, Emrick GE, de Monroy M. Cultivating men’s interest in family planning in rural El Salvador. Stud Fam Plann. 2005;36(3):173–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2005.00060.x

- Weis J, Festin M. Implementation and scale-up of the Standard Days Method of family planning: a landscape analysis. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2020;8(1):114–124. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00287

- Hartmann M, Gilles K, Shattuck D, Kerner B, Guest G. Changes in couples’ communication as a result of a male-involvement family planning intervention. J Health Commun. 2012;17(7):802–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2011.650825

- Wegs C, Creanga AA, Galavotti C, Wamalwa E. Community dialogue to shift social norms and enable family planning: an evaluation of the Family Planning Results Initiative in Kenya. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153907. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153907

- Greene M, Levack A. Synchronizing Gender Strategies: A Cooperative Model for Improving Reproductive Health and Transforming Gender Relations. Population Reference Bureau; 2010. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.igwg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/synchronizing-gender-strategies.pdf

- Pietromonaco PR, Overall NC. Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic may impact couples’ relationships. Am Psychol. 2021;76(3):438–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000714

- Pearson E, Andersen KL, Biswas K, Chowdhury R, Sherman SG, Decker MR. Intimate partner violence and constraints to reproductive autonomy and reproductive health among women seeking abortion services in Bangladesh. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;136(3):290–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12070

- Reed E, Saggurti N, Donta B, et al. Intimate partner violence among married couples in India and contraceptive use reported by women but not husbands. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;133(1):22–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.10.007

- Silverman JG, Challa S, Boyce SC, Averbach S, Raj A. Associations of reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence with overt and covert family planning use among married adolescent girls in Niger. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;22:100359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100359

- Seth K, Nanda S, Sahay A, Verma R, Achyut P. “It’s on Him Too” – Pathways to Engage Men in Family Planning: Evidence Review. International Center for Research on Women; 2020. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Couple-Engage-Evidence-Review.pdf

- Boyce SC, Uysal J, DeLong SM, et al. Women’s and girls’ experiences of reproductive coercion and opportunities for intervention in family planning clinics in Nairobi, Kenya: a qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00942-7

- Wood SN, Kennedy SR, Akumu I, et al. Reproductive coercion among intimate partner violence survivors in Nairobi. Stud Fam Plann. 2020;51(4):343–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12141

- Pomales TO. Men’s narratives of vasectomy: rearticulating masculinity and contraceptive responsibility in San José, Costa Rica. Med Anthropol Q. 2013;27(1):23–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12014

- Bukar M, Audu BM, Usman HA, El-Nafaty AU, Massa AA, Melah GS. Gender attitude to the empowerment of women: an independent right to contraceptive acceptance, choice and practice. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33(2):180–183. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2012.737052

- Mboane R, Bhatta MP. Influence of a husband’s healthcare decision making role on a woman’s intention to use contraceptives among Mozambican women. Reprod Health. 2015;12:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-015-0010-2

- Chanthakoumane K, Maguet C, Essink D. Married couples’ dynamics, gender attitudes and contraception use in Savannakhet Province, Lao PDR. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(sup2):1777713. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2020.1777713

- USAID. Office of Population and Reproductive Health. Bureau for Global Health. Essential Considerations for Engaging Men and Boys for Improved Family Planning Outcomes. USAID; 2018. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1864/Engaging-men-boys-family-planning-508.pdf

- Bartel D, M Greene. Involving everyone in gender equality by synchronizing gender strategies. PRB. September 10, 2018. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://scorecard.prb.org/involving-everyone-in-gender-equality-by-synchronizing-gender-strategies/

- Kim, YM. Counselling and communicating with men to promote family planning in Kenya and Zimbabwe. In: Programming for Male Involvement In Reproductive Health. World Health Organization; 2002:29–41. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67409/WHO_FCH_RHR_02.3.pdf

- Watts C, Heise L, Ellsberg M, Garcia-Moreno C. Putting Women First: Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Research on Domestic Violence Against Women. World Health Organization; 2001. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.who.int/gender/violence/womenfirtseng.pdf

- Fleming PJ, Silverman J, Ghule M, et al. Can a gender equity and family planning intervention for men change their gender ideology? Results from the CHARM intervention in rural India. Stud Fam Plann. 2018;49(1):41–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12047

- Breakthrough Research. Considerations and Guidance for Using Routine and Program Monitoring Data for SBC Evaluation. Programmatic Research Brief. Population Council; 2021. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/BR_RoutineData_Brief.pdf

- Silva M, Edan K, Dougherty L. Monitoring the Quality Branding Campaign Confiance Totale in Côte d’Ivoire. Breakthrough Research Technical Report. Population Council; 2021. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/BR_Confiance_Totale_Rprt.pdf

- Edmeades J, Stevanovic-Fenn N. Understanding the Male Life Course: Opportunities for Gender Transformation. Background Paper. Georgetown University, Institute for Reproductive Health; 2020. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://irh.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Life-Course-Background-Paper-USAID-11_19_20_2-1.pdf

- Hess R, Meekers D, Storey JD. Egypt’s Mabrouk! Initiative: a communication strategy for maternal/child health and family planning integration. In: Obregon R, Waisbord S, eds. The Handbook of Global Health Communication. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:374–407. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118241868.ch18

- Speizer IS, Corroon M, Calhoun LM, Gueye A, Guilkey DK. Association of men’s exposure to family planning programming and reported discussion with partner and family planning use: the case of urban Senegal. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204049. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204049

- Kincaid DL. Social networks, ideation, and contraceptive behavior in Bangladesh: a longitudinal analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(2):215–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00276-2

- Behera J, Sarkar A, Mehra S, Sharma P, Mishra SK. Encouraging young married women (15-24 years) to improve intra-spousal communication and contraceptive usage through community based intervention package in rural India. J Contracept Stud. 2016;1:4. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://contraceptivestudies.imedpub.com/encouraging-young-married-women1524-years-to-improve-intraspousalcommunication-and-contraceptive-usagethrough-community-based-inte.php?aid=11144

- Ashfaq S, Sadiq M. Engaging the Missing Link: Evidence From FALAH for Involving Men in Family Planning in Pakistan. Case Study. Population Council, The Evidence Project; 2015. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh/490/

- Mahmood, A. Birth Spacing and Family Planning Uptake in Pakistan: Evidence From FALAH. Population Council; 2012. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh/122/

Suggested citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). Promoting healthy couples’ communication to improve reproductive health outcomes. Washington, DC: USAID; 2022 Apr. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/

briefs/couple-communication

Acknowledgements

This brief was written by: Robert Ainslie (Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs), Angie Brasington (USAID), Arzum Ciloglu (Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs), Leanne Dougherty (Population Council), Busara Drezgic (EngenderHealth), Jill Gay (What Works Association), Lucia Gumbo, (USAID/Zimbabwe) and Geoffrey Rugaita (Independent Consultant, Kenya).

This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Eftu Ahmed (IntraHealth), Joya Banerjee (CARE), Netra Bhatta, Maria Carrasco (USAID), Kate Doyle, Lenette Golding (Save the Children), Kamden Hoffman (Corus International), Joan Kraft, Alice Payne Merritt, Bertha Migodi, Annie Portela (WHO), Caitlin Thistle, and Danette Wilkins.

The World Health Organization/Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception

The HIP Partnership is a diverse and results-oriented partnership encompassing a wide range of stakeholders and experts. As such, the information in HIP materials does not necessarily reflect the views of each co-sponsor or partner organization.

To engage with the HIPs please go to: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/engage-with-the-hips/