Community Health Workers: Bringing family planning services to where people live and work

Background

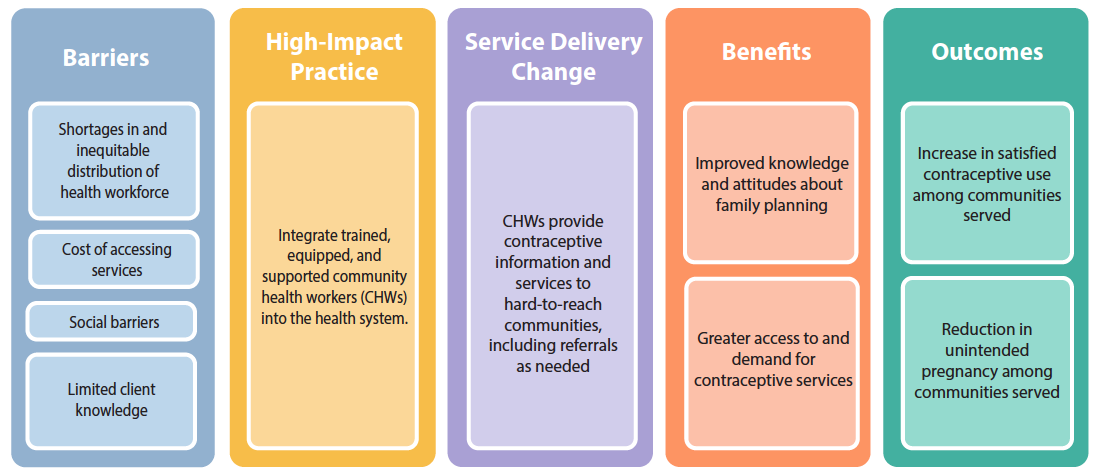

When appropriately designed and implemented, community health worker (CHW) programs can increase use of contraception, particularly where unmet need is high, access is low, and geographic or social barriers to use of services exist. CHWs are particularly important to reducing inequities in access to services by bringing information, services, and supplies to women and men in the communities where they live and work rather than requiring them to visit health facilities, which may be distant or otherwise inaccessible.

CHWs “provide health education, referral and follow up, case management, and basic preventive health care and home visiting services to specific communities. They provide support and assistance to individuals and families in navigating the health and social services system” (ILO, 2008). The level of education and training, the scope of work, and the employment status of CHWs vary across countries and programs. CHWs are referred to by a wide range of titles such as a “village health worker,” “community-based distributor,” “community health aide,” “community health promoter,” “health extension worker,” or “lay health advisor.”

Integrating CHWs into the health system is one of several proven “high-impact practices in family planning” (HIPs) identified by a technical advisory group of international experts. A proven practice has sufficient evidence to recommend widespread implementation as part of a comprehensive family planning strategy, provided that there is monitoring of coverage, quality, and cost as well as implementation research to strengthen impact (HIPs, 2014). For more information about other HIPs, see http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/overview.

What challenges can CHWs help countries address?

CHWs address geographic access barriers caused by health worker shortages. “The World Health Report 2006” identified 57 countries facing critical shortages in health personnel. Moreover, most highly trained medical staff are concentrated in wealthier, urban areas (WHO, 2006). “Community health worker programs have emerged as one of the most effective strategies to address human resources for health shortages while improving access to and quality of primary healthcare” (Liu et al., 2011).

CHWs may reduce financial barriers for clients. Even in settings with “free” services, clients may be asked to pay consultation fees or informal charges before receiving services. For example, in rural Muheza, Tanzania, where CHWs provide services to one-third of modern contraceptive users, a higher proportion of contraceptive users who accessed services at a health facility paid for services (61%) than those accessing services from a CHW (25%) (Simba et al., 2011).

CHWs can address the social barriers that inhibit family planning use. Analysis of DHS data shows that women who are young, poor, less educated, or who live in rural areas have more difficulty meeting their family planning needs than their more advantaged counterparts. These inequities exist in all regions of the world except Central Asia; the gaps are larger and more common in sub-Saharan Africa than in other regions. In addition, many countries in sub-Saharan Africa demonstrate little or no progress toward reducing the equity gap (Ortayli & Malarcher, 2010; Ross, 2015). CHWs who come from disenfranchised communities can provide a bridge between individuals and communities and the health system. In Guatemala, a higher proportion of clients of CHWs were indigenous women (83%) than clients using clinic-based services (17%) (Fernández et al., 1997). In Uganda and Ethiopia, a greater percentage of clients of CHWs were unmarried (16% and 12%, respectively) than clients at clinics (9% and 8%, respectively), and in Uganda, a lower percentage of clients of CHWs had supportive husbands than clinic clients (41% vs. 52%, respectively) (Prata et al., 2011; Stanback et al., 2007). In Sierra Leone, nearly a third of clients receiving injectable contraception from CHWs were 18 years of age or younger (MSI, 2015).

CHWs reach women whose mobility is constrained by social norms. In some countries, cultural practices restrict women’s movement or their ability to make independent decisions. CHWs overcome such barriers by bringing services to where women and their families work and live.

© 2014 Haydee Lemus/PASMO PSI Guatemala, Courtesy of Photoshare

What is the impact?

CHW programs increase contraceptive use in places where use of clinic-based services is not universal. A review of community-based programs in sub-Saharan Africa found six of seven experimental studies demonstrated a significant increase in contraceptive use or reduction in fertility rates (Philips et al., 1999). The magnitude of effect varied depending on the context and design of the CHW program. In Madagascar, individuals who had direct communication with CHWs were 10 times more likely to use modern contraceptives than individuals who did not have contact with CHWs (Stoebenau & Valente, 2003). In Afghanistan, a CHW program increased contraceptive usage 24 to 27 percentage points in areas where initial use was very low (beginning at 9% to 24% contraceptive prevalence) (Huber et al., 2010).

CHW programs may reduce unmet need in countries with large rural populations. Countries such as Bangladesh and Indonesia have strong CHW programs in which CHWs deliver a significant share of modern methods to their communities. In Bangladesh 23%, and in Indonesia 19%, of modern contraceptive users indicate CHWs as their last source of contraceptive supply. In both these countries, there is also low unmet need for family planning in rural areas (14 and 11%, respectively) (Prata et al., 2005).

Cost per Couple-Years of Protection (CYP)1 by Service Delivery Mode2

| Service Delivery Mode | |

|---|---|

| Clinics + CHWs | |

| Average Cost in US$ per CYP (Range) | $9 (1–17) |

| Clinics | |

| Average Cost in US$ per CYP (Range) | $13 (1–30) |

| CHWs | |

| Average Cost in US$ per CYP (Range) | $14 (5–19) |

| Service Delivery Mode | Average Cost in US$ per CYP (Range) |

|---|---|

| Clinics + CHWs | $9 (1–17) |

| Clinics | $13 (1–30) |

| CHWs | $14 (5–19) |

1 CYP is the estimated contraceptive protection provided by contraceptive methods during a one-year period.

2 Original analysis was based on community-based distribution (CBD). Reference to CBD has been changed to CHW to maintain consistency with the terminology used in this brief.

Source: Adapted from Prata et al., 2005; data from Huber & Harvey, 1989.

CHWs working in coordination with a functioning health system can reduce fertility rates. In Ghana, in communities where CHWs operated in conjunction with community volunteers, the total fertility rate was reduced by one birth after three years compared with communities with the typical health care system (Phillips et al., 2006). Bangladesh experienced an estimated 25% reduction in fertility rates over an eight-year period among women who were visited every two weeks by a trained CHW. The program also achieved a statistically significant reduction in maternal mortality rates among the intervention group during the same time period (Koenig et al., 1988).

Programs that link CHWs with clinic-based service delivery can be cost-effective. Cost and cost-effectiveness of CHW programs vary depending on the program setting, worker compensation, maturity of the program, strategies used for training and supervision, and the number of clients served (FRONTIERS et al., 2002). A review of family planning programs in 10 developing countries found that programs that combined CHWs with clinic-based service delivery were more cost-effective than either clinic-based or CHW programs alone (see Table 1).

CHWs can expand contraceptive method choice by providing a wide range of methods safely and effectively. To assist countries in optimizing health worker performance, WHO developed a comprehensive set of evidence-based recommendations to facilitate task sharing for key, effective maternal and newborn interventions, including contraceptive provision (WHO, 2012). While most CHWs provide condoms and pills within their communities, evidence shows that these workers are also highly effective at providing and referring for other methods (Perry et al., 2014).

- Based on evidence from several projects in multiple countries, experts found that the autonomous provision of injectable contraception by trained and supported CHWs was safe, effective, and acceptable to clients (Abdul-Hadi et al., 2013; WHO et al., 2010). A study in Ethiopia demonstrated that provision of injectable contraceptives by CHWs proved to be safe and acceptable among women, and clients of CHWs were less likely to discontinue use of contraception over three cycles than clients who acquired their injection through clinic-based services (Prata et al., 2011).

- A study in India demonstrated that low-literacy CHWs can effectively provide the Standard Days Method (SDM)™ to their clients (Johri et al., 2005). CHWs in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guatemala, and the Philippines provide SDM and support continuing users (Georgetown University, 2011; Georgetown University, 2003; Suchi & Batz, 2006).

- A study in India demonstrated that CHWs, even those who are illiterate, can teach the Lactational Amenorrhea Method (LAM) and accurately counsel women on LAM use and postpartum contraception (Georgetown University, 2008; Sebastian et al., 2012).

- A study in Bangladesh demonstrated that all categories of health care providers, including NGO outreach workers, could effectively provide emergency contraception (EC). More than 90% of the workers mastered the important points of EC use and instructed their clients appropriately (Khan et al., 2004).

- CHWs in Ethiopia and Nigeria are expanding access to implants at the community level (Charyeva et al., 2015; MOH Ethiopia, 2012).

CHWs can also mobilize contraceptive use of clinic-based methods through counseling and referrals. Evidence from Ethiopia demonstrates that, even where CHWs are restricted to providing a limited set of contraceptive methods, they are capable of increasing use of other methods, including long-acting reversible methods, through proper counseling and referrals to clinic-based services. An analysis of DHS data found that in areas where CHWs were operating, use of injectables, implants, and IUDs was higher than the national average even though CHWs did not provide these methods directly (Tawye et al., 2005). A review of strategies to increase IUD use concluded that community-based contraceptive counseling and referral can double the rate of IUD use among women of reproductive age (Arrowsmith et al., 2012).

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

Integrate CHWs Into the Health System

- Link CHWs to the health system with well-defined referral and supervision structures. In Ethiopia, where contraceptive use increased from 15% in 2005 to 29% in 2011 after the Health Extension Workers program was established, CHWs receive regular supervision by supervisors who are linked to health facilities. In Madagascar, CHWs report monthly to the head provider of the health center and receive supportive supervision.

- Consider using mobile technology, which may provide a cost-effective approach to link CHWs with the health system. A program in Malawi supported SMS communication to improve information sharing between CHWs and their district teams. SMS participants (n=95) reported and received feedback from their supervisor at least five times per month at an average of US$0.61 per communication. In comparison, those with cell phones but no access to SMS (n=95) had only four contacts per month with their supervisors at $2.70 per contact, and the control group (n=95) without cell phone access had six contacts per month but at $4.56 per contact. The most frequent SMS communication was regarding commodity stock-outs, which ultimately resulted in stock-out reductions (Lemay, 2012).

- Integrate management information systems. In Ethiopia, CHWs began keeping a “family folder” for every family in the catchment area of a health post. The family folder used a simplified tickler system, whereby health cards were organized in wooden boxes according to the month in which follow-up services were needed for family members. If a health card was left in the previous month’s box, it alerted the health worker that a service had not been provided, prompting the health worker to reach out to the family to provide care. Health extension workers also use the boxes/health cards to plan follow-up with pregnant women, family planning clients, and children for immunization (Chewicha & Azim, 2013).

Train CHWs

- Implement a comprehensive training program that includes incremental, practical, competency-based training and mechanisms to reinforce skills. In Madagascar, more education, weekly volunteer hours, and refresher training were associated with higher performance scores among CHWs providing family planning services (Gallo et al., 2013).

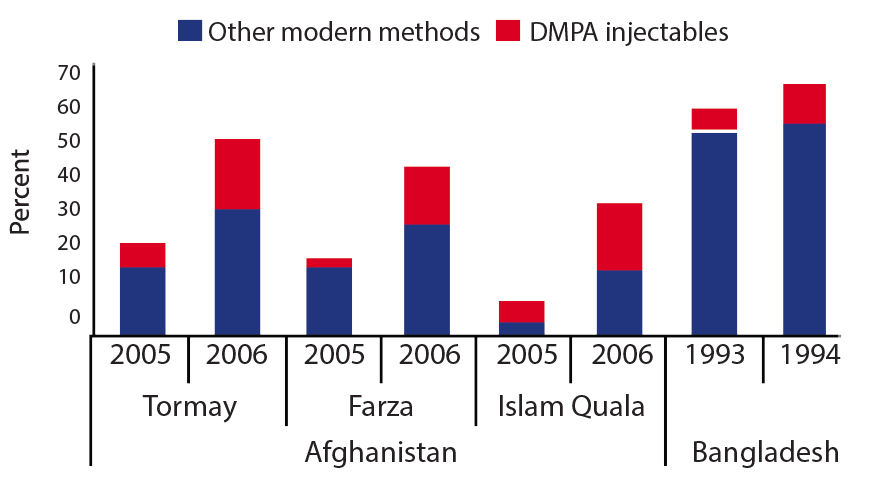

- Expand the variety of methods provided by CHWs. When contraceptive services are provided directly by CHWs, uptake is significantly greater than when CHWs offer referrals only. (Perry et al., 2014; Viswanathan et al., 2012). Evidence from four programs that introduced community-based provision of injectables into existing CHW programs documented increased uptake of injectables as well as of other modern methods (see Figure 2).

- Train and engage CHWs in behavior change communication efforts. In India, women living in communities where CHWs supported a behavior change communication campaign focused on healthy timing and spacing of pregnancy were 3.5 times more likely to be using modern contraception at 9 months postpartum than women living in communities where CHWs were not involved in this communication campaign (Sebastian et al., 2012).

Equip CHWs

Success of CHW programs is directly linked to continuous product availability at the community level. Supply chains are optimal when data and product flow between CHWs and the larger health system are in sync.

- Invest attention and funding to improve supply chains all the way to CHWs. When designing an effective supply chain for CHW programs, consider organizational capacity, CHW literacy levels, ways to track logistics management information systems forms, and ways to track and aggregate data (Hasselberg & Byington, 2010). CHWs should be included in the design and integration of supply chain infrastructures (Chandani et al., 2014). Sustaining product availability at the community level requires dependable national product availability and a functional supply chain that can reliably deliver products to CHWs.

-

Make appropriate and timely community logistics data visible at both the health center and the district level. Such data is a prerequisite for managers and quality improvement teams to regularly monitor the supply chain and to respond in a timely and targeted way. Implementing an SMS and web-based mHealth system, where data are transformed into relevant, usable reports, can significantly improve timely and accurate availability and usability of community health logistics data at all levels of the supply chain (Chandani et al., 2014). Using mobile phones, a CHW program in Malawi was able to decrease stock-outs of essential medicines, lower communication costs, expand service coverage, and implement a more efficient referral system (Campbell et al., 2014).

-

Implement multilevel quality improvement teams that connect CHWs, health center staff, and district staff to reinforce the correct and consistent use of resupply procedures and to address routine bottlenecks in the supply chain. Such teams were associated with significantly improved product availability in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Rwanda (Chandani et al., 2014).

Support CHWs

- Employ incentives to retain CHWs. In Ethiopia and Mozambique, recruiting and retaining CHWs was related to greater compensation and a sense of worthiness. Such strategies also influence decisions toward a potential CHW career choice (Maes & Kalofonos, 2013). Incentives, both financial and non-financial, were associated with greater retention among volunteer CHWs in urban Dhaka (Alam et al., 2012). In many countries, CHWs are paid, full-time members of community health systems. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, the One Million Community Health Workers Campaign is training, deploying, and integrating CHWs into the health system. In India, 600,000 CHWs are paid through a fee-for-service system. In Brazil, community health agents are part of family health teams that now care for 110 million people (Singh & Chokshi, 2013).

-

Certify CHWs to visibly recognize their contributions. Certification helps to professionalize the community health workforce, driving quality standards for training and performance.

-

Engage communities in planning, monitoring, and supporting CHWs. In Madagascar’s successful national CHW program, CHWs are supervised by the Community Health Committee.

-

Recruit CHWs from the beneficiary communities. Studies consistently show that CHWs reach women of similar ages and household socioeconomic status to their own (Bhutta et al., 2010; Foreit et al., 1992; Lewin et al., 2010; Lewin et al., 2005; Subramanian et al., 2013). Programs that aim to serve disadvantaged communities will need to recruit, train, and support CHWs from these communities.

-

Consider recruiting men as CHWs. A review of community-based programs found that men have great potential in increasing distribution of male condoms, which provide dual protection against both unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV. Male CHWs are acceptable in countries as diverse as Kenya, Pakistan, and Peru. Evidence shows that male CHWs distribute more condoms than female CHWs. Male CHWs also appear to serve more male clients. In controlled studies, male CHWs distributed contraceptives that amounted to equal or greater CYPs than female CHWs (Green et al., 2002).

-

Be dynamic and evolve with changing needs. Community-based programs are most effective when they evolve with the changing needs of the communities they serve. A study of Profamilia clinics in Colombia showed that once CHWs improved contraceptive knowledge and use among the community (55% to 65% among ever-married women), contraceptive social marketing programs were more profitable than, and equally effective as, CHW programs (Vernon et al., 1988). Similarly, in Bangladesh, after a door-step family planning delivery program attained high contraceptive knowledge and prevalence (55% contraceptive prevalence rate), success was maintained through a less intensive and more cost-effective centralized depot approach (Routh et al., 2001). However, some regions of Bangladesh still need door-step delivery to address the social and cultural norms that continue to inhibit women’s freedom of movement and that impede consistent contraceptive use.

Planning, Implementing, and Scaling-Up CHW Programs

| Program Considerations | |

|---|---|

| General Approach | |

| Factors Contributing to Success | Understanding that CHW programs are complex and challenging to sustain. |

| Factors Contributing to Failure | Misconception that CHW programs are simple and self-sustaining. |

| Considerations for Scale-Up | Plan for scale-up from the beginning. Make a systematic plan for scale-up based on country strategy and existing program. |

| Range of Services | |

| Factors Contributing to Success | Broad range of services and commodities that reflect the preferences of the communities served. |

| Factors Contributing to Failure | Preoccupation with a single commodity or service resulting in failure to develop a comprehensive service system. |

| Considerations for Scale-Up | Adapt service package to meet community needs. |

| Community Involvement & Political Support | |

| Factors Contributing to Success | Community involvement, particularly at the strategic planning stage. CHW selection guided by community opinion. |

| Factors Contributing to Failure | Lack of broad political support. Responsibility of galvanizing and mobilizing communities rests solely with CHWs. |

| Considerations for Scale-Up | Sustain engagement of community and health system with leadership from district and health center staff. |

| Sustainability vs. Compensation | |

| Factors Contributing to Success | Paid workers perform better than volunteers. Completely voluntary schemes do not work well. If workers are not paid, some other motivational scheme is required, and the scope of work for unpaid volunteers should be realistic. |

| Factors Contributing to Failure | Overemphasis on sustainability and cost recovery, which may be incompatible with the objective of reaching poor and remote communities. |

| Considerations for Scale-Up | Advocate with governments, donors, and community for support. Provide cost-benefit information. When planning the program, consider costs of scaling-up as well as of maintaining the program at scale. |

| Quality & Social Barriers | |

| Factors Contributing to Success | CHWs trained and engaged in social and behavior change communication activities. |

| Factors Contributing to Failure | Failure to address quality and social barriers to contraceptive use. |

| Considerations for Scale-Up | Improve quality continuously through active organizational management. Address broad contextual and health system barriers. |

| Supervision of CHWs | |

| Factors Contributing to Success | Supportive, rather than directive, CHW supervision. |

| Factors Contributing to Failure | Lack of connection with larger health system. |

| Considerations for Scale-Up | Consider innovations to support remote case management, such as mobile technologies. |

| Management Information Systems | |

| Factors Contributing to Success | Management information systems that support the informational needs of CHWs as a first priority. |

| Factors Contributing to Failure | Stock-outs threaten support for and reputation of CHWs. |

| Considerations for Scale-Up | Consider SMS and Web-based mHealth systems, where data are transformed into relevant, usable reports and shared on a timely basis. |

| Referrals & Linkages | |

| Factors Contributing to Success | CHWs linked to and have ongoing relationship with facility-based services. |

| Factors Contributing to Failure | CHW system viewed as separate from the health system. |

| Considerations for Scale-Up | Ensure dependable national-level availability of products and a supply chain that facilitates efficient movement of products to resupply points as well as data to and from all levels of the system. |

| Program Considerations | Factors Contributing to Success | Factors Contributing to Failure | Considerations for Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Approach | Understanding that CHW programs are complex and challenging to sustain. | Misconception that CHW programs are simple and self-sustaining. | Plan for scale-up from the beginning. Make a systematic plan for scale-up based on country strategy and existing program. |

| Range of Services | Broad range of services and commodities that reflect the preferences of the communities served. | Preoccupation with a single commodity or service resulting in failure to develop a comprehensive service system. | Adapt service package to meet community needs. |

| Community Involvement & Political Support | Community involvement, particularly at the strategic planning stage. CHW selection guided by community opinion. | Lack of broad political support. Responsibility of galvanizing and mobilizing communities rests solely with CHWs. |

Sustain engagement of community and health system with leadership from district and health center staff. |

| Sustainability vs. Compensation | Paid workers perform better than volunteers. Completely voluntary schemes do not work well. If workers are not paid, some other motivational scheme is required, and the scope of work for unpaid volunteers should be realistic. |

Overemphasis on sustainability and cost recovery, which may be incompatible with the objective of reaching poor and remote communities. | Advocate with governments, donors, and community for support. Provide cost-benefit information. When planning the program, consider costs of scaling-up as well as of maintaining the program at scale. |

| Quality & Social Barriers | CHWs trained and engaged in social and behavior change communication activities. | Failure to address quality and social barriers to contraceptive use. | Improve quality continuously through active organizational management. Address broad contextual and health system barriers. |

| Supervision of CHWs | Supportive, rather than directive, CHW supervision. | Lack of connection with larger health system. | Consider innovations to support remote case management, such as mobile technologies. |

| Management Information Systems | Management information systems that support the informational needs of CHWs as a first priority. | Stock-outs threaten support for and reputation of CHWs. | Consider SMS and Web-based mHealth systems, where data are transformed into relevant, usable reports and shared on a timely basis. |

| Referrals & Linkages | CHWs linked to and have ongoing relationship with facility-based services. | CHW system viewed as separate from the health system. | Ensure dependable national-level availability of products and a supply chain that facilitates efficient movement of products to resupply points as well as data to and from all levels of the system. |

Source: Adapted from Chandani et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2011; Phillips et al. 1999; and WHO, 2007.

The Community-Based Family Planning Toolkit, is a one-stop source for knowledge and lessons learned about community-based family planning programs. Available from: www.k4health.org/toolkits/communitybasedfp

Supply Chain Models and Considerations for Community-Based Distribution Programs: A Program Manager’s Guide, presents four supply chain models for community-based programs with guidance and lessons learned on supply chain functions that can be adapted and applied to a variety of country contexts. Available from: www.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id=11132&lid=3

cStock, a RapidSMS, open-source, Web-accessible logistics information management system, helps CHWs and health centers streamline reporting and resupply of up to 19 health products, including contraceptives, managed at the community level while enhancing communication and coordination between CHWs, health centers, and districts. Learn more at: sc4ccm.jsi.com/emerging-lessons/cstock/

Community Health Systems Catalog, is an interactive Web-based reference tool on community health systems, including structure, management, staffing, and services, in a number of countries. Available from: www.advancingpartners.org/resources/chsc

References

Abdul-Hadi RA, Abass MM, Aiyenigba BO, Oseni LO, Odafe S, Chabikuli ON, et al. The effectiveness of community based distribution of injectable contraceptives using community health extension workers in Gombe State, Northern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2013;17(2):80-88.

Alam K, Khan JA, Walker DG. Impact of dropout of female volunteer community health workers: An exploration in Dhaka urban slums. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:260. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-260

Arrowsmith M, Aicken C, Majeed A, Saxeen S. Interventions for increasing uptake of copper intrauterine devices: systematic review and meta-analysis. Contraception. 2012;86(6):600-605.

Bhutta ZA, Lassi ZS, Pariyo G, Huicho L. Global experience of community health workers for delivery of health related millennium development goals: a systematic review, country case studies, and recommendations for integration into national health systems. Geneva: World Health Organization, Global Health Workforce Alliance; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/workforcealliance/knowledge/publications/CHW_FullReport_2010.pdf

Campbell N, Schiffer E, Buxbaum A, McLean E, Perry C, Sullivan T. Taking knowledge for health the extra mile: participatory evaluation of a mobile phone intervention for community health workers in Malawi. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2(1):23-34. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00141

Chandani Y, Andersson S, Heaton A, Noel M, Shieshia M, Mwirotsi A, et al. Making products available among community health workers: evidence for improving community health supply chains from Ethiopia, Malawi, and Rwanda. J Glob Health. 2014;4:020405. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/25520795/

Charyeva Z, Oguntunde O, Orobaton N, Otolorin E, Inuwa F, Alalade O, et al. Task shifting provision of contraceptive implants to community health extension workers: results of operations research in northern Nigeria. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(3):382-394. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00129

Chewicha K, Azim T. Community health information system for family centered health care: scale-up in Southern nations, nationalities and people’s region. Policy and Practice: Information for Action [quarterly health bulletin of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health]. 2013;5(1):49-53. Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/measure/publications/ja-13-161

Fernández VH, Montufar E, Ottolenghi E, Enge K. Injectable contraceptive service delivery provided by volunteer community promoters. Unpublished project report: Population Council; 1997.

Foreit JR, Garate MR, Brazzoduro A, Guillen F, Herrera MC, Suarez FC. A comparison of the performance of male and female CBD distributors in Peru. Stud Fam Plann. 1992;23(1):58-62.

Frontiers in Reproductive Health Program (FRONTIERS); Family Health International; Advance Africa. Best practices in CBD programs in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons learned from research and evaluation. Washington (DC): FRONTIERS; 2002.

Gallo, MF, Walldorf J, Kolesar R, Agarwal A, Kourtis AP, Jamieson DJ, et al. Evaluation of a volunteer community-based health worker program for providing contraceptive services in Madagascar. Contraception. 2013;88(5):657-665. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4453873/

Georgetown University, Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH). A powerful framework for women: introducing the Standard Days Method to Muslim couples in Kinshasa. Washington (DC): Georgetown University, IRH; 2011. Available from: http://irh.org/resource-library/a-powerful- framework-for-women-introducing-the-standard-days-method-to-muslim-couples-in-kinshasa/

Georgetown University, Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH). Lactational Amenorrhea Method (LAM) projects in India. Washington (DC): Georgetown University, IRH; 2008. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PDACL615.pdf

Georgetown University, Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH). Introducing the Standard Days Method of family planning into Kaanib: testing counseling strategies. Unpublished report; 2003.

Green CP, Joyce S, Foreit JR. Using men as community-based distributors of condoms. Washington (DC): Population Council, Frontiers in Reproductive Health; 2002. Available from: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/frontiers/pbriefs/male_CBDs_brf.pdf

Hasselberg E, Byington J. Supply chain models and considerations for community-based distribution programs: a program manager’s guide. Arlington (VA): John Snow, Inc., for the Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition; 2010. Available from: http://www.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id=11132&lid=3

High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Family planning high-impact practice list. Washington (DC): USAID; 2014. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/high-impact-practices-in-family-planning-list

Huber D, Saeedi N, Samadi AK. Achieving success with family planning in rural Afghanistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(3):227-231. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471%2FBLT.08.059410

Huber SC, Harvey PD. Family planning programmes in ten developing countries: cost effectiveness by mode of service delivery. J Biosoc Sci. 1989;21(3):267–77.

International Labour Organization (ILO). International standard classification of occupations, 2008 revision. Geneva: ILO; 2008. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/isco/docs/gdstruct08.doc

Johri L, Panwar DS, Lundgren R. Introduction of the Standard Days Method in CARE-India’s community-based reproductive health programs. Washington (DC): Georgetown University, Institute for Reproductive Health; 2005. Available from: http://irh.org/resource-library/introduction- of-the-standard-days-method-in-care-indias-community-based-reproductive-health-programs/

Khan ME, Hossain SM, Rahman M. Introduction of emergency contraception in Bangladesh: using operations research for policy decisions. Washington (DC): Population Council; 2004. Available from: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/frontiers/FR_FinalReports/Bang_EC.pdf

Koenig MA, Fauveau V, Chowdhury A, Chakraborty J, Khan MA. Maternal mortality in Matlab, Bangladesh: 1976-85. Stud Fam Plann. 1988;19(2):69-80.

Lemay NV, Sullivan T, Jumbe B, Perry CP. Reaching remote health workers in Malawi: baseline assessment of a pilot mHealth intervention. J Health Communication. 2012; 17 Suppl 1:105-117.

Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk B, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD004015.

Lewin S, Dick J, Pond P, Zwarenstein M, Aja G, van Wyk B, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD004015.

Liu A, Sullivan S, Khan M, Sachs S, Singh P. Community health workers in global health: scale and scalability. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78(3):419-435.

Maes K, Kalofonos I. Becoming and remaining community health workers: perspectives from Ethiopia and Mozambique. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:52-59. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3732583/

Malarcher S, Meirik O, Lebetkin E, Shah I, Spieler J, Stanback J. Provision of DMPA by community health workers: what the evidence shows. Contraception. 2011;83(6):495-503.

Marie Stopes International (MSI). Monitoring and evaluation of task-sharing of Depo-Provera to community health workers in Sierra Leone. London: MSI; 2015.

Ministry of Health (MOH) [Ethiopia]. Implanon and other family planning methods uptake in a sample of focus Woredas (June 2009 – Dec 2010). Washington (DC): PROGRESS; 2012. Available from: http://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/family-planning-uptake-ethiopia.pdf

Ortayli N, Malarcher S. Equity analysis: identifying who benefits from family planning programs. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41(2):101-108.

Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:399-421. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182354

Phillips JF, Bawah AA, Binka FN. Accelerating reproductive and child health programme impact with community-based services: the Navrongo experiment in Ghana. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(12):949-955. Available from: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/84/12/06-030064.pdf

Phillips JF, Greene WL, Jackson EF. Lessons from community-based distribution of family planning in Africa. New York: Population Council; 1999. Available from: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/wp/121.pdf

Prata N, Gessesew A, Cartwright A, Fraser A. Provision of injectable contraceptives in Ethiopia through community-based reproductive health agents. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:556–564. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3150764/pdf/BLT.11.086710.pdf

Prata N, Vahidnia F, Potts M, Dries-Daffner I. Revisiting community-based distribution programs: are they still needed? Contraception. 2005;72(6):402-407.

Ross J. Improved reproductive health equity between the poor and the rich: an analysis of trends in 46 low- and middle-income countries. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015;3(3):419-445. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00124

Routh S, Ashraf A, Stoeckel J, Khuda B. Consequences of the shift from domiciliary distribution to site-based family planning services in Bangladesh. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2001;27(2):82-89. Available from: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/2708201.html

Sebastian MP, Khan ME, Kumari K, Idnani R. Increasing postpartum contraception in rural India: evaluation of a community-based behavior change communication intervention. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;38(2):68-77. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1363/3806812

Shieshia M, Noel M, Andersson S, Felling B, Alva S, Agarwal S, et al. Strengthening community health supply chain performance through an integrated approach: using mHealth technology and multilevel teams in Malawi. J Glob Health. 2014;4(2):020406. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4267094/

Simba D, Schuemer C, Forrester K, Hiza M. Reaching the poor through community-based distributors of contraceptives: experiences from Muheza district, Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2011;13(1):1-7.

Singh P, Chokshi DA. Community health workers: a local solution to a global problem. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(10):894-896. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1305636

Stanback J, Mbonye A, Bekiita M. Contraceptive injections by community health workers in Uganda: a non-randomized trial. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:768–773. Available from: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/10/07-040162/en/

Stoebenau K, Valente TW. Using network analysis to understand community-based programs: a case study from highland Madagascar. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2003;29(4):167–173. Available from: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/2916703.html

Subramanian L, Oliveras E, Bowser D, Okunogbe A, Mehl A, Jacinto A, et al. Evaluating the coverage and cost of community health worker programs in Nampula province in Mozambique. Watertown (MA): Pathfinder; 2013. Available from: http://www.pathfinder.org/publications-tools/evaluating-the-coverage-and-cost-chw-programs-mozambique.html

Suchi T, Batz B. Strengthening services and increasing access to the Standard Days Method in the Guatemala Highlands. Washington (DC): Georgetown University, Institute for Reproductive Health; 2006. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/ PDACH685.pdf

Tawye Y, Jotie F, Shigu T, Ngom P, Maggwa N. The potential impact of community-based distribution programmes on contraceptive uptake in resource-poor settings: evidence from Ethiopia. Afr J Reprod Health. 2005;9(3):15-26.

Vernon R, Ojeda R, Townsend MC. Contraceptive social marketing and community-based distribution-systems in Colombia. Stud Fam Plann. 1988;19(6 Pt 1):354–360.

Viswanathan K, Hansen PM, Rahman MH, Steinhardt L, Edward A, Arwal SH, et al. Can community health workers increase coverage of reproductive health services? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(10):894-900. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech-2011-200275

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO recommendations: optimizing health worker roles to improve access to key maternal and newborn health interventions through task shifting. Geneva: WHO; 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/978924504843/en/

World Health Organization (WHO). Community health workers: what do we know about them? Geneva: WHO; 2007. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/round9_7.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO). The world health report 2006: working together for health. Geneva: WHO; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/

World Health Organization; US Agency for International Development; Family Health International (FHI). Community-based health workers can safely and effectively administer injectable contraceptives: conclusions from a technical consultation. Research Triangle Park (NC): FHI; 2010. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADS867.pdf

View the previous version of this HIP published in October 2012.

Suggested Citation

High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Community health workers: bringing family planning services to where people live and work. Washington (DC): USAID; 2015. Available from: http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/community-health-workers

Acknowledgements

This document was originally drafted by Julie Solo and Shawn Malarcher. Updated by Clifton Kenon. Critical review and helpful comments were provided by Hashina Begum, Jeanette Cachan, Brenda Doe, Ellen Eiseman, Bill Finger, Rachel Hampshire, Sarah Harbison, Susan Igras, Roy Jacobstein, Victoria Jennings, Eugene Kongnyuy, Kirsten Krueger, Rebecka Lundgren, Morrisa Malkin, Cat McKaig, Erin Mielke, Danielle Murphy, Nuriye Ortayli, Leslie Patykewich, Amy Ucello Matthew Phelps, Juncal Plazaola-Castano, Ruwaida Salem, Adriane Salinas, Valerie Scott, Jeff Spieler, Patricia Stephenson, and Tara Vecchione. Updated review by Moazzam Ali, Tariq Azim, Yasmin Chandani, Maureen Corbett, Liz Creel, Ellen Eiseman, Mary Eluned Gaffield, Victoria Graham, Lillian Gu, Roy Jacobstein, Niranjala Kanesathasan, Candace Lew, Constance Newman, Tanvi Pandit-Rajani, Shannon Pryor, Rushna Ravji, Suzanne Reier, Boniface Sebikali, James Shelton, Gail Snetro, John Stanback, Sara Stratton, and Mary Vandenbroucke.

This HIP brief is endorsed by: Abt Associates, Care, Chemonics International, EngenderHealth, FHI 360, Georgetown University/ Institute for Reproductive Health, International Planned Parenthood Federation, IntraHealth International, Jhpiego, John Snow, Inc., Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, Management Sciences for Health, Marie Stopes International, Palladium, PATH, Pathfinder International, Population Council, Population Reference Bureau, Population Services International, Save the Children, University Research Co., LLC, United Nations Population Fund, and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

The World Health Organization/Department of Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: http://www.who.int/topics/family_planning/en/.

For more information about HIPs, please contact the HIP team.