Comprehensive Policy Processes: The agreements that outline health goals and the actions to realize them

Background

The development, implementation, and monitoring of policies supportive of rights-based family planning is essential in creating an enabling environment for and guiding the provision of high-quality family planning programs and services. A policy is a formal document in which a government or other institution outlines its goals and the approaches, actions, and authorities for achieving those goals.1 Policies range from legal and regulatory frameworks, to macro-level policies, strategies, and budgets, to operational guidelines, protocols, and procedures (Box 1) These formal documents guide the development, implementation, and (sometimes) monitoring of systems, programs, and services. For instance, national family planning programs are often enshrined in reproductive health policies that codify reproductive health as a right, establish goals and objectives, and outline what systems should be developed and what programs and services should be implemented to meet those goals and objectives.

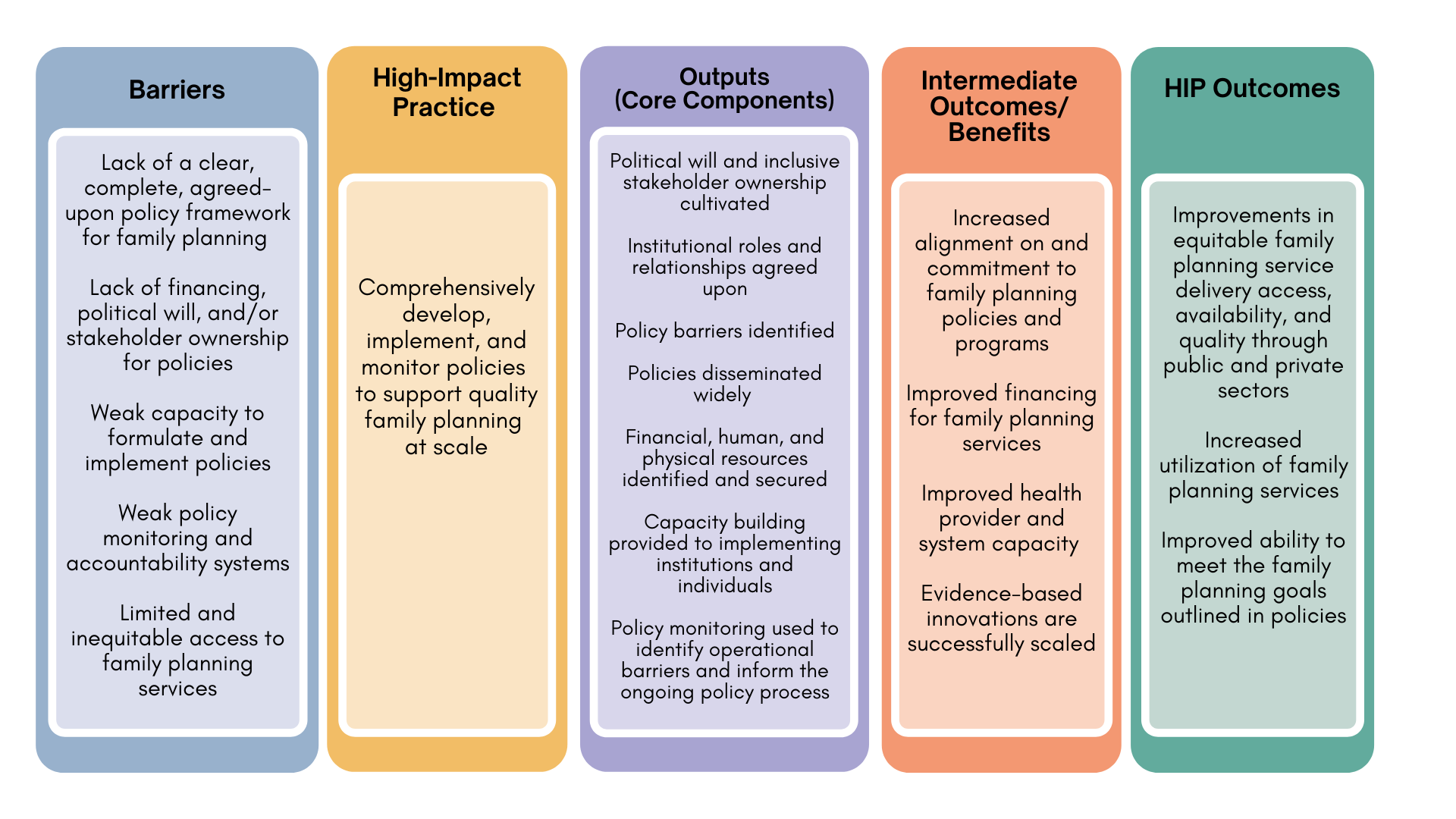

Policies are often developed without adequate attention to the range of actions necessary to achieve the goals of the policy.2–4 When this happens, a policy remains a mere document. The actions necessary for policy success are collectively referred to in this brief as comprehensive policy development, implementation, and monitoring, or more succinctly as a comprehensive policy process.

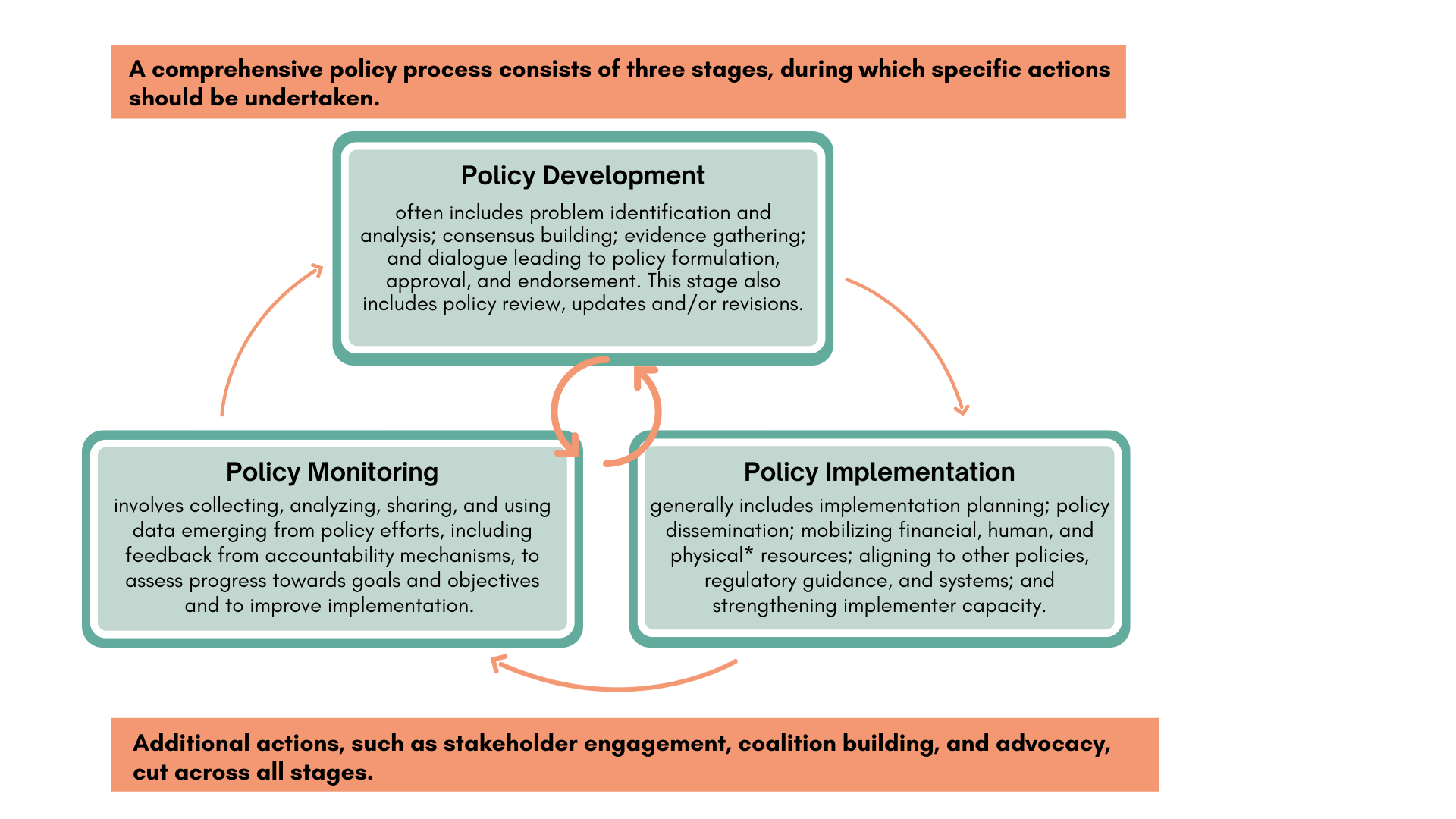

Comprehensive policy development, implementation, and monitoring involves attention to all three policy stages and the specific actions of each stage. The visual representation of this practice (Figure 1) draws from several policy implementation frameworks (PATH, 2021a; HP+, n.d.-a; Hardee et al., 2012).1,5,6 While depicted as a cycle, it is often an iterative process, with multiple stages and actions happening at once. For instance, planning for policy monitoring should begin when the policy is still in development.

The application of a comprehensive policy process usually falls along a spectrum between “inadequate” and “strong,” with some stages and actions well addressed and others not, or partially so. For instance, conclusions from a study on the scale-up of a youth-friendly service delivery model in Ethiopia were that “despite a conducive policy environment, supportive stakeholders, favorable environment, and financial support for trainings, statistically significant increases in long-acting reversible contraceptive uptake occurred at only 2 of the 8 health centers.” This limited success was attributed primarily to lack of broader financial resources and operational barriers within the health system.9

Comprehensively developing, implementing, and monitoring policies is one of several “high-impact practices” (HIPs) in family planning identified by a technical advisory group of international experts. For more information about HIPs, see http://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/about.

- Legal and regulatory framework policies authorize the provision of services and include national constitutions, laws, and budgets, as well as the regulation and/or registration of contraceptives and other drugs.

- Macro-level policies provide high-level guidance as to how program and services should be implemented, and include national and subnational policies and strategies, such as national reproductive health policies and primary health care strategies.

- Operational policies provide more specific guidance and include service delivery guidelines, costed implementation plans, essential medicine lists, and directives regarding health information systems.7,8

See the 2013 version of the HIP Policy brief for examples of policies from each level.

What challenges can comprehensive policy development, implementation, and monitoring help address?

Inattention to human rights and inequitable access to care can be addressed through comprehensive policy processes. Policies play an important role in ensuring equitable access and a rights-based approach to voluntary family planning for all people, especially those that have been historically underserved. Rights-based policies, when effectively implemented, support the obligations that governments make when ratifying international human rights treaties and articulate political commitment to ensuring rights and equity.10 For example, in 2017 Madagascar passed a new reproductive health and family planning law, replacing the previous legal framework that prohibited the provision of contraception to youth and to married women without spousal consent. The new law guarantees a right to access family planning services regardless of age, marital status, or other forms of discrimination.11

Policy efforts that lack attention to the full range of actions within a comprehensive policy process (Figure 1) are less likely to result in improvements in family planning outcomes. For example, a qualitative review of obstacles to advance women’s health in Mozambique found that “participants unanimously argued that women’s health is already sufficiently prioritized in national health policies and strategies (…); the problem, rather, is the implementation and execution of existing (…) policies and programs.”12 In another example, Malawi has clear guidelines that call for provider-initiated family planning counseling for all reproductive-age HIV clients, but a 2019 assessment found that that only a small percentage of clients were being counseled on family planning.13

Evolving evidence and changing contexts can leave programs and services out-of-date. Use of a comprehensive policy process, including regular policy review and updates, can support safe, efficient, and quality services as new evidence, practices, and contraceptive methods emerge. For example, following several studies that showed the acceptability and feasibility of subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA-SC), countries began registering the product and adding it to their national family planning programs through policy changes.14–16 In addition, changes in context, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, can alter the landscape in which policies are implemented.

Despite ample evidence, proven best practices are not consistently scaled and sustained. Several studies describing the scale-up of new practices have highlighted the importance of comprehensive policy development, implementation, and monitoring.9,17–20 For example, a qualitative assessment of factors perceived to be affecting the scale-up of community-based distribution of injectable contraception in Nigeria found that the existence of supportive policies and health worker training and capacity building were among the factors that facilitated scale-up of the new practice. Scale-up was also hindered by policy-related factors, including a lack of ownership in the policy among key government stakeholders and lack of support from health professional groups.21

Policy implementation is the set of actions undertaken to ensure the enabling environment exists for programs to be successfully executed (e.g., integrating a new contraceptive method into supply chains and pre-service training curriculum for health care workers). Program implementation includes the actions that happen on a day-to-day basis to deliver the program (e.g., health care workers offering the methods to clients). In some situations, policy implementation may encompass program implementation. For example, training of health workers may be considered policy implementation, program implementation, or both.

What is the evidence that comprehensively developing, implementing, and monitoring policies leads to high impact?

Several countries that have included family planning within well-implemented health and/or economic and social policies have seen strong increases in voluntary contraceptive use and other family planning measures. Family planning programs benefited from the inclusion within these broader policies.22,23 Success of these policies was attributed to the specific actions from within the comprehensive policy process, such as use of data and evidence, consensus building, alignment with other policies, and broad stakeholder engagement. Additionally, studies in India and Kenya showed that capacity building and/or training on new and revised policies for implementers can support achievement of the intended health outcomes.24,25 More information on how strong national policies influence family planning outcomes can be found in the 2013 version of the HIP Policy brief.8

CASE STUDIES: When a policy is comprehensively developed, implemented, and monitored, it can lead to successful scale-up of the practice and/or program described in the policy—and to improved service delivery and increased use of family planning services.

Guinea offers a successful example of policy development and implementation for a high impact practice. Proactively offering voluntary contraceptive counseling and services as part of postabortion care (PAC) is a proven HIP.26 Guinea has included PAC within several policies and guidelines since it was piloted in 1998. A study with data collected in 2014 assessed provision of contraception as part of PAC services and found that more than 95% of PAC clients were counseled on family planning and 73% of clients voluntarily left the facility with a method. Based on stakeholder interviews, the study authors attribute these high rates of coverage and uptake to the comprehensive inclusion of the practice within national policies, standards, guidelines, and other tools; engagement of champions within and beyond the Ministry of Health to advocate for PAC and the financial resources to support PAC implementation; and roll-out of provider training on clinical PAC guidelines and standards. The policy and its implementation were also credited with expanding access to PAC services for previously underserved populations. Contraceptive counseling rates were consistent across PAC facilities, even in rural areas with fewer providers. And as of 2018, PAC services expanded to 10 additional sites, of which six were in regions that did not previously have PAC services.19

Implementation and monitoring of a primary health care policy in Ghana illustrates the long and iterative process often required. In 2000, the Ghanaian government approved a policy to support nationwide scale-up of Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS), a primary health care program that includes provision of family planning, childhood immunizations, and other services by community-based nurses and trained volunteers. Implementation of this complex policy has occurred over two decades, with decision makers iterating on the policy and its implementation to accelerate expansion of the program and ensure that it leads to high-quality and equitable services. Policy implementation has been decentralized, as the policy outlines several steps that communities are expected to complete as precursors to program implementation. These steps include community mapping, community engagement, and mobilization of physical and human resources.27,28

Policy monitoring during the first decade of implementation revealed slow and inconsistent nationwide roll-out of the policy. Despite the decentralized and community-based implementation leading to widespread buy-in, there was insufficient dissemination of and orientation to the policy and inadequate funding to support initial costs.28

In 2010, the Ghanaian government pilot-tested a program to accelerate implementation of the CHPS policy. The Ghana Essential Health Interventions Program (GEHIP), used demonstration sites to support orientation and capacity building for implementation, increased financial resources, strengthened the monitoring system, and addressed operational barriers, such as supply chain challenges. GEHIP doubled the rate of coverage and percent of the population reached by CHPS compared to districts with more passive implementation.27 GEHIP had a significant impact on modern contraception use, which increased among married women in GEHIP regions by 80% relative to non-GEHIP districts. Unmet need for contraception was not affected by GEHIP, which is attributed to social constraints to contraceptive use that were not addressed by the GEHIP/CHPS model.29

Based on the GEHIP results and data from continued policy monitoring, the Ghanaian government made revisions to the original CHPS policy and expanded implementation support to additional districts. CHPS coverage is expected to be nationwide by 2022.28 Ongoing research explores how to further improve family planning outcomes through future CHPS policy iterations.30

How to do it: Tips from implementation experience

Across all stages of a comprehensive policy process

Stakeholder engagement varies in process and intensity by the type of stakeholder and policy context. It can range from holding inclusive dialogues, to coalition building, to supporting political commitment.

- Create inclusive dialogues that address concerns and prevent resistance. Resistance to a policy can be a barrier to the success of the policy. (Hudson et al., 2019; Qiu et al., 2019) This was the case during the scale-up of a task-shifting policy in Nigeria in which resistance from health professional bodies was identified as a major policy implementation barrier. (Akinyemi et al., 2019) Such resistance should be monitored for. It can be addressed and potentially prevented by regularly meeting with a wide variety of stakeholders (Box 3) to share policy updates and seek input. Given potential changes in personnel and context, engagement should be ongoing.

- Politicians and other decision makers, such as funders

- Policy makers and others who work in government agencies within and beyond ministries of health

- Subnational health officials

- Frontline implementers, including providers, supervisors, and others who work in public, private, and nonprofit health programs

- Professional associations and other organizations that support health programming

- Academic institutions and other organizations that can support evidence generation, policy analysis, and advocacy

- Community and civic organizations, including groups representing women, youth, and marginalized populations

- Commercial and private sector actors, including drug shops, pharmacies, and insurance companies

- Media, including community radio stations

- Community members and all populations affected by the policy, including refugees

- Build and sustain active coalitions to support the policy process. Collaborative partnerships that build on the relative strengths of a range of stakeholders can facilitate policy implementation.3,22,24 Actors in the partnership—or policy team—can be encouraged to take active roles in supporting the comprehensive policy process.

- Establish political will and commitment. Ownership of a policy has been cited as a key determinant of policy outcomes.17,18,21,28 Identifying and asking champions to lead aspects of the comprehensive policy process can help build ownership and commitment. See also the HIP brief on galvanizing political commitment.

During policy development

- Consider the policy environment and how it may be continually evolving. When engaging in a policy change process, advocates should learn how policy decisions are made, what approvals will be needed, and what the timeline might be. Key factors are the extent to which decisions are made at high levels by a few individuals or through collaborative agreement, and through formal processes or unofficial channels.

- Design policies with implementation and monitoring in mind. Policies should address the root causes of agreed-upon problems; be realistic in relation to available resources; and be explicit about roles and expectations. If a new practice or program is included in the policy, it should be evidence-based, feasible at scale, and tailored to the context. For instance, policy changes may diverge from prevailing social norms; this may hinder implementation, but can also be a strategy for working towards norm change. For instance, when a national law changes to allow young people to access contraceptive services without parental approval, this can help shift social norms towards being more accepting of that practice. Policies should be rights-based and enable equitable access to services. See also the HIP Strategic Planning Guide on creating equitable access to high-quality family planning.

- Plan for both regular updates and unanticipated changes to the policy. A comprehensive policy process includes a timeline and plan to regularly review the policy against monitoring data and emerging evidence and changing context, as well as to make updates as needed.

During policy implementation

- Consider the extent to which policy implementation should be centralized. Policy implementation is often described as either top-down or bottom-up, though it is usually a combination. In top-down approaches, central-level actors direct implementation in a structured manner. Bottom-up approaches allow decentralized actors to determine how to best implement the policy in their local context. Policies that are implemented in a top-down manner are often specific directives, while bottom-up policy approaches are often more complex and expansive, such as primary health care policies.2 The amount of ambiguity in the policy and level of contention elicited by the policy, as well as the extent to which decision-making powers have been devolved to subnational units, should be considered in determining whether policy implementation should be top-down and/or bottom-up.2,31

- Harmonize policies and systems across levels and domains. Alignment across national and operational policies can be a factor in how successfully a policy is implemented.12,19 As a policy is being developed and monitored, mapping of other relevant policies, systems, and tools should be done to determine if the policy is in alignment and if not, where changes will need to be made. Updates may need to be made to clinical guidelines, operations procedures, provider scopes of practice, essential medicine lists, monitoring systems, supply plans, training curricula, laws, regulations, and other documents. The policy’s effect on private and nonprofit health institutions should also be considered.

- Reflect resource needs and realities and develop strategies to act on them. The lack of financial resources is a common reason why policies are not implemented or do not meet their goals.9 In Mozambique, an assessment of women’s health policies found that policies were written without taking into account resource limitations at subnational levels, setting unrealistic targets and expectations without providing adequate funding.12 A costing exercise should be done during the policy development stage, and reviewed during implementation and monitoring, to confirm that policies have realistic budget estimates. Estimates should take into account human and physical resources needs such as hiring and training staff and procuring supplies and equipment. For government policies that will require external support, strategies for mobilizing resources from donors, the private sector, and/or other stakeholders should also be developed.

- Disseminate policies widely, through all levels of the health system and to stakeholders. Inadequate policy dissemination has been noted in several contexts.12,32 Frontline implementers must be aware of policies, have access to them in the appropriate language(s), and have support to follow them. Allow time for orientation to the new policy for all levels of implementers. Training and/or continuing education may also be needed, as well as updates to the pre-service training curriculum.24,25 In addition, policy information disseminated to the media and civil society organizations can create awareness at the community level, which is essential to social accountability for policy implementation.

During policy monitoring

- Strengthen monitoring and evaluation of the policy and its implementation. Monitoring of policy implementation has been successfully used to support improvements in the policy process.18 Policy monitoring should assess implementation milestones across the health systems and scan for operational barriers and areas in which policy implementation may be stalled. It should also draw on health management information system data and/or program-level monitoring to determine if the desired outcomes are being met. Implementers should monitor for unforeseen negative consequences of policies, such as diminished equity or rights in programs and services. A list of illustrative indicators for assessing policy efforts to support family planning programs can be found in the 2013 HIP Policy brief.8

- Strengthen accountability mechanisms. Accountability mechanisms support transparent communication between community members and health system actors, including policy makers. They enable those affected by policies to provide their feedback on how policies are being implemented. More information can be found in the HIP brief on Strategic Social Accountability and in the 2013 HIP Policy brief.8

Implementation Measurement

The HIPs partnership is developing a set of measures to assess the scale and quality of implementation of the eight service delivery HIPs, which will be helpful in defining policy implementation measures for specific policies and practices. The following measures are illustrative of the type of measures that can be applied to policies generally.

- Extent to which policies are up-to-date and harmonized across the health system, e.g., in training curricula, supervision tools, supply and logistics management systems, monitoring systems, and budgets.

- Annual budget expenditures to support policy implementation.

- Percentage/number of facilities or implementation sites that have the financial, human, and physical resources available to implement the policy.

Priority Research Questions

- What is the relative importance of specific aspects or actions within a comprehensive policy process for achieving family planning related goals and meeting users’ needs?

- Can utilization of a comprehensive policy process from the earliest stages of policy creation accelerate the timeline for achieving the goals outlined in the policy?

- How can comprehensively developing, implementing, and monitoring policies be used to increase equity in terms of access to services by diverse populations?

- Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Policy Portal

- From Capital to Clinic: A Resource for Effective Advocacy for Policy Implementation

- Taking the Pulse of Policy: The Policy Implementation Assessment Tool

- The Costed Implementation Plan Resource Kit: Tools and Guidance to Develop and Execute Multi-Year Family Planning Plans

References

- Health Policy Plus (HP+). What is policy? Definitions and key concepts. HP+; date unknown.

- PATH. Capital to Clinic: Exploring Successful Health Policy Implementation. PATH; 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://path.azureedge.net/media/documents/Capital_to_Clinic_white_paper_FINAL.pdf

- Hudson B, Hunter D, Peckham S. Policy failure and the policy-implementation gap: can policy support programs help? Policy Design Pract. 2019;2(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2018.1540378

- Campos PA, Reich MR. Political Analysis for Health Policy Implementation. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(3):224–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2019.1625251

- PATH. From Capital to Clinic: A Resource for Effective Advocacy for Policy Implementation. PATH; 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://path.azureedge.net/media/documents/Capital_to_Clinic_tool_FINAL_highres.pdf

- Hardee K, Irani, L, MacInnis R, Hamilton M. Linking Health Policies With Health Systems and Health Outcomes: A Conceptual Framework. Health Policy Project; 2012. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/index.cfm?id=publications&get=pubID&pubId=186

- Hardee K. Approach for Addressing and Measuring Policy Development and Implementation in the Scale-Up of Family Planning and Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health Programs. Health Policy Project; 2013. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/184_PolicyapproachreportFinal.pdf

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Family planning policy: building the foundation for systems, services, and supplies. USAID; 2013. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/previous-brief-versions

- Fikree FF, Zerihun H. Scaling up a strengthened youth-friendly service delivery model to include long-acting reversible contraceptives in Ethiopia: a mixed methods retrospective assessment. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2020;9(2):53–64. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2019.76

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ensuring Human Rights in the Provision of Contraceptive Information and Services: Guidance and Recommendations. WHO; 2014. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/human-rights-contraception/en/

- Health Policy Plus (HP+). Madagascar passes landmark reproductive health and family planning law. Accessed May 12, 2022. http://www.healthpolicyplus.com/madagascarHFPLaw.cfm

- Qiu M, Sawadogo-Lewis T, Ngale K, Cane RM, Magaço A, Roberton T. Obstacles to advancing women’s health in Mozambique: a qualitative investigation into the perspectives of policy makers. Glob Health Res Policy. 2019;4:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-019-0119-x

- McGinn EK, Irani L. Provider-initiated family planning within HIV services in Malawi: did policy make it into practice? Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(4):540–550. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00192

- Askew I, Wells E. DMPA-SC: an emerging option to increase women’s contraceptive choices. Contraception. 2018;98(5):375–378. https://doi.org10.1016/j.contraception.2018.08.009

- Cole, K., & Saad, A. (2018). The coming-of-age of subcutaneous injectable contraception. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018;6(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00050

- Guiella G, Turke S, Coulibaly H, Radloff S, Choi Y. Rapid uptake of the subcutaneous injectable in Burkina Faso: evidence from PMA2020 cross-sectional surveys. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018;6(1):73–81. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00260

- Ouedraogo L, Habonimana D, Nkurunziza T, et al. Towards achieving the family planning targets in the African region: a rapid review of task sharing policies. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-01038-y

- Tilahun Y, Lew C, Belayihun B, Lulu Hagos K, Asnake M. Improving contraceptive access, use, and method mix by task sharing Implanon insertion to frontline health workers: the experience of the Integrated Family Health Program in Ethiopia. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(4):592–602. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00215

- Pfitzer A, Hyjazi Y, Arnold B, et al. Findings and lessons learned from strengthening the provision of voluntary long-acting reversible contraceptives with postabortion care in Guinea. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(Suppl 2):S271–S284. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00344

- Benevides R, Fikree F, Holt K, Forrester H. Four Country Case Studies on the Introduction and Scale-up of Emergency Contraception. Evidence to Action Project; 2014. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.pathfinder.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Global-Emergency-Contraception-Four-Country-Case-Studies.pdf

- Akinyemi O, Harris B, Kawonga M. Health system readiness for innovation scale-up: the experience of community-based distribution of injectable contraceptives in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):938. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4786-6

- USAID/Africa Bureau, USAID/Population and Reproductive Health, Ethiopia Federal Ministry of Health, Malawi Ministry of Health, Rwanda Ministry of Health. Three Successful Sub-Saharan Africa Family Planning Programs: Lessons for Meeting the MDGs. USAID; 2012. Accessed May 12, 2022. http://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/africa-bureau-case-study-report.pdf

- World Bank. Demographic Transition: Lessons From Bangladesh’s Success Story. World Bank; 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33672

- Chokshi H, Sethi H. From Policy to Action: Using a Capacity-Building and Mentoring Program to Implement a Family Planning Strategy in Jharkhand, India. Health Policy Project; 2014. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/368_ProcessDocumentationReportJharkhand.pdf

- Stanback J, Griffey S, Lynam P, Ruto C, Cummings S. Improving adherence to family planning guidelines in Kenya: an experiment. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(2):68–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzl072

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Postabortion family planning: a critical component of postabortion care. USAID; 2019. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/postabortion-family-planning/

- Awoonor-Williams JK, Phillips JF, Bawah AA. Catalyzing the scale-up of community-based primary healthcare in a rural impoverished region of northern Ghana. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2016;31(4):e273–e289. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2304

- Phillips JF, Binka FN, Awoonor-Williams JK, Bawah AA. Four decades of community-based primary health care development in Ghana. In: Bishai D, Schleiff M, eds. Achieving Health for All: Primary Health Care in Action. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1353/book.77991

- Asuming PO, Bawah AA, Kanmiki EW, Phillips JF. Does expanding community-based primary health care coverage also address unmet need for family planning and improve program impact? Findings from a plausibility trial in northern Ghana. J Glob Health Sci. 2020;2(1):e18. https://doi.org/10.35500/jghs.2020.2.e18

- Biney AAE, Wright KJ, Kushitor MK, et al. Being ready, willing and able: understanding the dynamics of family planning decision-making through community-based group discussions in the Northern Region, Ghana. Genus. 2021;77(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-020-00110-6

- Matland RE. Synthesizing the implementation literature: the ambiguity-conflict model of policy implementation. J Public Adm Res Theory. 1995;5(2):145–174. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1181674

- Mashalla YJ, Sepako E, Setlhare V, Chuma M, Bulang M, Massele AY. Availability of guidelines and policy documents for enhancing performance of practitioners at the primary health care (PHC) facilities in Gaborone, Tlokweng and Mogoditshane, Republic of Botswana. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2016;8(8):127–135. https://doi.org/10.5897/JPHE2016.0812

Suggested Citation

High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). Comprehensive policy processes: The agreements that outline health goals and the actions to realize them. Washington, DC: HIP Partnership; 2022 May. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/policy/

Acknowledgements

This brief was written by: Moazzam Ali (WHO), Bonnie Keith (PATH), Suzanne Kiwanuka (Makerere University), Gertrude Odezugo (USAID), Elizabeth Rottach (Palladium), Robyn Sneeringer (BMGF), Sara Stratton (Palladium), John Townsend (Population Council), Lucy Wilson (Consultant). It was updated from a previous version, published in 2013, available here.

This brief was reviewed and approved by the HIP Technical Advisory Group. In addition, the following individuals and organizations provided critical review and helpful comments: Saad Abdulmumin (BMGF), Maria Carrasco (USAID), Peter Gubbels (Groundswell International), Laura Hurley (Palladium), Josephine Kinyanjui (PATH), Joan Kraft (USAID), Lara Lorenzetti (FHI 360), Emeka Nwachukwu (USAID), Pellavi Sharma (USAID).

The World Health Organization/Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research has contributed to the development of the technical content of HIP briefs, which are viewed as summaries of evidence and field experience. It is intended that these briefs be used in conjunction with WHO Family Planning Tools and Guidelines: https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception

The HIP Partnership is a diverse and results-oriented partnership encompassing a wide range of stakeholders and experts. As such, the information in HIP materials does not necessarily reflect the views of each co-sponsor or partner organization.

To engage with the HIPs please go to: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/engage-with-the-hips/